It’s been a rough week for popular music with the death of two of the most important figures in the culture of the last 70 years. On the surface, Brian Wilson and Sly Stone could not be further apart. Wilson was the sun-kissed, clean cut all-American kid singing pop songs with his family about surfing, girls, and cars. Stone was the perpetually high black hippie singing funk and soul songs with a racially and sexually integrated band about togetherness, self-empowerment, and enjoying life to the fullest. Wilson marked the first half of the 1960s, Stone was a product of the second half of that decade.

On further reflection, several striking similarities are also evident. Both were geniuses. Both bands were built around family members. Both made it into the 1970s with increasingly scattered results. Both were casualties of drugs and mental illness. Both were unbelievably influential on their peers and their descendants.

Sly Stone, born Sylvester Stewart in 1943, was a disc jockey, producer, and musician in San Francisco who led the Family Stone, a funk outfit that had a great love for all types of music and incorporated rock, soul, psychedelia, gospel, and pop into their sound and blew the doors off of the boundaries of the music scene. Beginning with his Top Ten hit, “Dance to the Music” he began a string of classic songs and albums that redefined the music of black America. This was not the hardcore funk of James Brown, nor was it the Memphis soul of Otis Redding, or the gorgeous pop symphonies of Motown. This was, well, all of that thrown in a blender. The result was unique to Sly and the Family Stone, but others were paying attention.

It’s simply impossible to imagine the sound of black music in the 1970s and beyond without hearing and understanding Sly and the Family Stone. Beginning with his first breakout albums, Music of My Mind and Talking Book, and culminating with the magisterial Songs in the Key of Life, Stevie Wonder had clearly been paying close attention to Sly. Without Sly, there is no Philly soul, no Jacksons, no Parliament-Funkadelic, no Earth, Wind, and Fire, no Spinners, no War, no latter-day Temptations. Follow the trail into the 80s and beyond and there’s no Terence Trent D’Arby, no Prince, no Red Hot Chili Peppers, no Fishbone, no OutKast, no Vintage Trouble. James Brown can rightfully claim the credit for inventing rap, but one wonders if the more music-oriented rappers would have picked up their instruments without Sly leading the way. All these bands and performers were paying homage to Sly Stone in their different ways. Even Talking Heads’ more funk-oriented songs from the early 80s were directly inspired by Sly.

Stone peaked with 1968’s album Stand! and the three singles that he released to close out the decade. “Hot Fun in the Summertime” remains one of the all-time great summer songs, as good as anything Brian Wilson’s brothers had released. The double A-side that he released at year’s end, “Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” and “Everybody Is A Star” pointed the way to the seventies on the first side and summarized Sly’s sixties on the second half.

Brian Wilson, the heart and soul of The Beach Boys, was a fragile genius who turned the California dream into a universal language. Born in 1942, Wilson’s early life was steeped in music but scarred by the abuse of his father, Murry, a domineering figure whose cruelty left lasting marks. It was a smack from the desperate wannabe songwriter Murry that rendered Brian deaf in one ear. Wilson’s genius took a while to become evident. The early Beach Boys, as enjoyable and as fun as they are, were mainly variations on a theme: surfing is cool, and life is best lived at the beach. But the genius was lurking all the time, poking his head up in introspective songs like “In My Room” that hinted at a more melancholy side to the songwriter. The musical and vocal arrangements were also getting more sophisticated. As a kid, sitting in front of the stereo with headphones on listening to the then-new Endless Summer compilation, I was drawn more to the intriguing arrangements of the music on “California Girls” and the vocals on “Help Me, Rhonda” than I was to “Surfin’ Safari”.

Still, nothing prepared the music-loving America of 1966 for the explosion of brilliance that was Pet Sounds. Surely the winner of any competition for “Worst Cover/Best Album” in history, Pet Sounds was Brian Wilson’s attempt to pick up the gauntlet the Beatles had thrown down with Rubber Soul. Brian has stated that his album was an effort to create something that had “more musical merit than the Beatles.” For their part, the Beatles flipped over the Beach Boys album. Paul McCartney still calls it his favorite album. It wasn’t the lyrics on Pet Sounds that were revolutionary, though they broke from surfing and cars. Singer Mike Love even complained about that to Brian, telling him to “stick to the formula.” No, it was the musical arrangements that completely upended rock music. This was music that demanded to be taken seriously. Even the brilliant musicians who provided the instrumentation, Los Angeles mainstays The Wrecking Crew, familiar and fluent in every type of music around at the time, were confused by what Wilson was asking for in the studio. Confused, but also in awe of the results. Harpsichords, tympanies, barking dogs, bicycle bells…nothing was off-limits in Wilson’s imagination. Anchored by “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” and “God Only Knows,” Pet Sounds remains one of the greatest albums ever recorded. And it was such a flop Capitol records rush-released a greatest hits album just two months later. The fact is that nobody (except other musicians) was ready to hear Brian Wilson’s genius yet.

Wilson’s brilliance reached its apogee with the following single, “Good Vibrations,” a song whose intricate arrangement stuns the listener to this day. But Wilson’s attempt at a follow up album, Smile, was mired in a sea of LSD, pot, and mental illness. He’d had a nervous breakdown in 1964 which led to him giving up touring to concentrate on the records, and now he had another, far more serious one. Smile was abandoned. Parts of it were released on the albums Smiley Smile and Wild Honey, providing a tantalizing glimpse into what might have been. While he “finished” Smile in 2004 as a solo artist, the fact remains that the full Beach Boys-treatment remains the great lost album of the sixties.

Wilson’s career was a rollercoaster of brilliance and breakdown. His mental health struggles, compounded by drug abuse and the manipulative control of psychologist Eugene Landy, derailed him for decades. Landy, initially a savior in the 1970s, became a Svengali-like figure, isolating Wilson until a 1992 lawsuit freed him. His wife and guardian Melinda Wilson died in 2024. Brian Wilson lived out his life suffering from dementia, a tragic ending to a tragic story.

Sly Stone’s life mirrored Wilson’s in its descent. Drug addiction, particularly cocaine, and erratic behavior unraveled his career by the mid-1970s. The Family Stone fractured, and Stone became a reclusive figure, his output dwindling as he battled personal demons. His later years were marked by legal troubles, financial ruin, and health issues, culminating in a prolonged battle with COPD that eventually killed him.

While their stories are tragic, the music they left behind stands testament to their genius. As the drugs got worse Sly Stone’s music turned dark, but his work from the sixties remains fresh, sunny, bold, and optimistic. It’s the perfect companion to the hot nights partying after spending the day on the beach, where Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys provide the soundtrack of the endless summer. The musical world is greatly diminished by their loss.

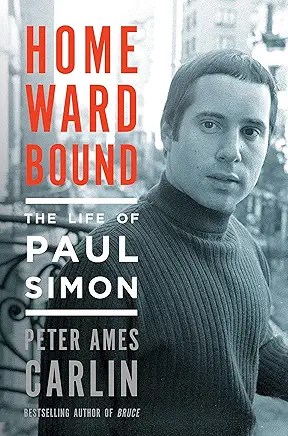

The poet half to Art Garfunkel’s one-man band has always been an interesting guy. Like Bob Dylan, he was a rock ‘n’ roll fan who went deep into the folk music scene only to reemerge with a sublime combination of the two genres. He achieved massive levels of fame and fortune, gathering critical hosannas the entire time, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice and now, in his 80s, is still releasing music. All of this, but Peter Ames Carlin’s 2016 biography was the first serious attempt at capturing this life on the page. The story covers Simon’s entire life from his days as a baseball fanatic kid growing up in Queens, New York through his years with Garfunkel and on through his solo career. Simon was not a particularly prolific artist, his solo albums being years apart, but the high quality of the work from “The Sound of Silence” to Graceland and beyond is unassailable.

The poet half to Art Garfunkel’s one-man band has always been an interesting guy. Like Bob Dylan, he was a rock ‘n’ roll fan who went deep into the folk music scene only to reemerge with a sublime combination of the two genres. He achieved massive levels of fame and fortune, gathering critical hosannas the entire time, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice and now, in his 80s, is still releasing music. All of this, but Peter Ames Carlin’s 2016 biography was the first serious attempt at capturing this life on the page. The story covers Simon’s entire life from his days as a baseball fanatic kid growing up in Queens, New York through his years with Garfunkel and on through his solo career. Simon was not a particularly prolific artist, his solo albums being years apart, but the high quality of the work from “The Sound of Silence” to Graceland and beyond is unassailable.