After the tension-filled sessions that created the White Album, the Beatles went back into the studio with a film crew in tow. The idea was to film a documentary about the making of the next album, provisionally called Get Back. It was a move to fulfill their old contractual obligation to make movies, but the timing couldn’t have been worse.

The concept was to go into the studio and “get back” to their roots as a four-piece rock ‘n’ roll band. Lennon, especially, wanted to avoid what he saw as the overproduction on albums like Sgt. Pepper.

The result was a disaster.

The rehearsals for the sessions were not done in their home base of EMI Studios, but in Twickenham Film Studios. Lennon, deeply in thrall to his new partner Yoko Ono, refusing ever to be apart from her, addicted to heroin, and creatively empty, was looking to break from the Beatles and was, at best, disinterested in the recording. Harrison was blossoming as a songwriter, turning out many of the best songs he ever wrote, and was frustrated that Lennon and McCartney were still treating him as an inferior. At one point he briefly quit the band. Ringo, too, felt apart from the band. McCartney was the only member who could still be called a Beatles fan. He tried desperately to rally the group into making a great album, but by taking over in the studio he became insufferable. Arguments abounded. Brian Epstein was dead and the band had no direction or focus. Even George Martin, their guiding light in the studio, was out of sorts when Paul brought in the producer Glyn Johns as an engineer. All of it was caught on film.

There was a brief bright spot. On the roof of EMI Studios, on a cold January day, the Beatles played one last live show. They only got through a few songs before the police shut them down, but for that brief period they were a band again: locked in, happy, and functioning as a single unit.

That moment was not enough. The music they had recorded in the studio was, as Lennon rightfully described it, “the shittiest load of badly recorded shit with a lousy feeling to it ever”.

Shortly after the rooftop concert, the band gave up and went their separate ways.

It was, of course, McCartney who reached out to the others, including George Martin, and got them to agree to give it one more try. Martin agreed on one condition: “We go in and do it like we used to.” The Beatles agreed.

The result was a triumph.

Abbey Road, the final album the Beatles recorded and thus their true swan song, is not without some flaws but it is a far more cohesive album than its all-white predecessor. It begins with John Lennon’s last famous Beatles song. “Come Together” started life as a campaign song for LSD-guru Timothy Leary’s brief attempt to become the governor of California with the slogan “Come together, join the party”, but Lennon was never able to get past the “come together” phrase. When Leary’s run ended as the result of a drug bust, Lennon scrapped the idea, kept the slogan, and crafted the song as we know it today. Beginning, and laced throughout, with John whispering the now creepily ironic line “Shoot me”, the lyrics are a hodgepodge of non sequiturs though there is speculation that each verse has cryptic allusions to the members of the band. The third verse clearly is about Lennon: “Bag Productions“, “walrus gumboot”, “Ono sideboard” can all easily be seen as self-referencing, but the theory falls apart when it gets to the other Beatles. Non sequiturs or not, it’s the music and the tagline (“Come together/Right now/Over me”) that make the song. Originally meant to be faster, it was McCartney who suggested they slow it down and add a swampy, bluesy feel to the track. Propelled by McCartney’s extraordinary bass line, and Lennon’s sublime vocal, it’s a devastating salvo to lead off the album. As wildly eclectic as the White Album was, there was nothing like “Come Together” in the band’s canon. The true tragedy of the song is that Lennon decided to nick a lyric from “You Can’t Catch Me” by Chuck Berry: “Here come a flat top/He was movin’ up with me” was modified into “Here come old flat top/He come groovin’ up with me.” Lennon was sued by Berry’s publisher and, as part of the setttlement, ended up being forced to record his sloppy, cocaine-fueled, largely uninspired solo album of covers, Rock ‘n’ Roll, in 1975.

As good as Lennon’s song was, it was immediately outclassed in every way by the song that followed. “Something” was George Harrison’s finest moment as a Beatle (though all votes for “Here Comes The Sun” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” will be counted). Upon hearing it none other than the Chairman of the Board (and no fan of rock music), Frank Sinatra, dubbed it “the greatest love song of the past 50 years” (though for years he gave the songwriting credit to Lennon and McCartney). Ironically, George also stole a key lyric, though he wasn’t sued. James Taylor, then a new recording artist signed to Apple Records, had a song on his fairly obscure first album called “Something In The Way She Moves” from which George blatantly, and admittedly, lifted his opening line. From there the songs parted. Taylor’s mid-tempo ballad, with a terribly cheesy harpsichord introduction, sounds like something Simon and Garfunkel might have done as album filler (though Taylor’s guitar playing shines far brighter than Simon’s ever did). Harrison’s “Something”, with its elegant guitar (bent strings, not a slide as many people think) and rocked up bridge, are immediately recognizable and timeless. Indeed, “Something” was so strong that even Lennon and McCartney conceded that it should be the A-side of their next single, a first for a George Harrison song. Lennon called it “the best on the album” and McCartney thought it the best song Harrison had written to that point. The song also contains one of the very best performances on a Beatles record from both Ringo, whose cascading rolls and fills both punctuate and push the ballad into rockier territory, and, especially, McCartney, whose wildly intricate bass line is one of the best he’s ever done.

McCartney takes the lead on “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”, another of his English music hall pastiche songs, a sort of psychopathic cousin to “When I’m Sixty-Four”. It’s as cute as any other song about bludgeoning people to death, maybe even cuter, with some nice guitar fills from George and excellent piano from Paul. There’s also a Moog synthesizer solo that never should have been recorded (generally true for all Moog synthesizer solos). The earworm chorus, complete with a hammer striking an anvil (for Richard Starkey of Liverpool, opportunity clanks!), makes the song instantly memorable even though it’s really very lightweight. Far better is “Oh! Darling”, which follows. It’s also something of a pastiche, but this time it hearkens back to the 1950s rock ‘n’ roll the Beatles loved so much, and features a larynx-shredding vocal from Paul. Lennon had made a pitch that he should sing it, since it fit his raw vocal style better, but there’s simply no denying the visceral thrill of McCartney employing almost every weapon in his arsenal.

Ringo marks his presence with “Octopus’s Garden”, a quirky song that was inspired by a conversation with a boat captain, but also a comment on Ringo’s wish to get away from the tension that came with being a Beatle in 1969. In some ways it can be seen as a companion piece to Ringo’s other nautical adventure, “Yellow Submarine”, with underwater sound affects, but also employs some of the country music sound from “Don’t Pass Me By”, especially on the chorus and George’s superb guitar solo. It’s the best song Ringo wrote as a Beatle (granted, there’s only “Don’t Pass” for competition), and it’s quite charming, but it’s also a light piece of fluff. A perfect Ringo song.

Side one ends with one of the rare “love it or hate it” songs in the Beatles canon. While it’s nowhere near as controversial as something like “Revolution 9”, many fans are divided on the merits of “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)”. The lyrics are simple: “I want you/I want you so bad/It’s driving me mad” and “She’s so heavy” are pretty much the total of the words, but the song clocks in at nearly eight minutes. The critics say the lyrics are too simple, the music too repetitive, the song too unlike any other Beatles song. Put me in the “love it” side of the argument. Yes, the words are simple but Lennon wasn’t trying to intellectualize his feelings for Yoko Ono, he was simply howling his raw, unbridled, lust. The music is a circular motif that borders on heavy metal, slathered in washes of synthesizer and Paul McCartney’s astounding lead bass playing. Layered guitars make the song sound impossibly big, and the repetition makes the listener feel like he’s being sucked into a maelström. The effect is hypnotic and the ending, a sudden cut to silence that is impossible to accurately time even with repeated listens, is as shocking as the piano chord that ends “A Day In The Life”.

The swirling darkness and Lennon’s primal vocal on “I Want You” offer a stark contrast to “Here Comes The Sun”, which kicks off side two of the album with a gorgeous, gentle guitar lick. This is George’s second song on the album, and stiff competition for his first, and the title of “best George Beatle song”. Written in Eric Clapton’s garden on a beautiful sunny day, the theme actually mirrors “Octopus’s Garden”. It’s George’s sigh of relief that he is, at least for that moment, away from the crushing pressure of the Beatles. It’s unfortunate that Lennon, recovering from a car accident, doesn’t appear on the song. Musically, it’s George, Paul, and Ringo at their best. The gentle, but insistent, guitar from Harrrison is given a great deal of urgency by Ringo’s sterling drumming and McCartney’s melodic bass line. It’s also one of George’s best vocal performances ever. With some subtle touches of synthesizer, strings, and woodwinds, it’s a perfect song to capture that feeling of springtime breaking through the cold clutches of Old Man Winter.

“Because” is the sun fully arrived. Based loosely on the chords of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” played backwards, and with sparse instrumentation, it’s perhaps the best example of the three-part harmonies of which the Beatles were capable. Sung by John, Paul, and George in harmony, with the vocals later triple-tracked to give the impression of nine voices, over George Martin’s harpsichord and John’s matching guitar, and underpinned by Paul’s simple bass and Harrison’s Moog flourishes, “Because” is one of the loveliest songs the Beatles ever did.

“Because” ends on a sustained “ahhh” that trails off into the ether and segues into the understated piano chords that herald one of the greatest of all late-era Beatles songs. “You Never Give Me Your Money” is McCartney’s song about the tension of being in the Beatles, their legal and accounting issues, and the desire to get away from it all. “You never give me your money/You only give me your funny paper”, Paul sang directly to Allen Klein, the ruthless and corrupt manager that the other Beatles wanted to fill the void left by Brian Epstein’s death (they didn’t know he was ruthless and corrupt yet, only that he managed the Rolling Stones and Mick Jagger had provided a very tepid endorsement). From this understated beginning, the song rapidly switches to Paul doing his best boogie-woogie piano (recorded at half-speed and then sped up) and Elvis voice, singing about the joys of the early days of the band, when the future stretched out in front of them. He’s singing about the beginnings of the band, hitting the road, all the money gone, with no idea of what the future might hold but knowing it was going to be great: “But oh, that magic feeling/Nowhere to go/Nowhere to go!”, followed by a wordless three-part harmony that leads into a quick, but ripping, guitar solo.

The third part of the song is Paul looking to recapture those early days, but this time with his new love, Linda Eastman, and with boatloads of money: “One sweet dream/Pack up the bags/Get in the limousine/Soon we’ll be away from here/Step on the gas and wipe that tear away.” While the third part of the song looks forward, it’s also somewhat sad as it’s Paul essentially acknowledging that his future does not lie with the Beatles. As the song ends in a firestorm of guitar and piano, Paul sings the childhood chant “1-2-3-4-5-6-7/All good children go to Heaven”. The song is a nice contrast to Starr’s and Harrison’s similarly themed songs. Ringo just wanted to get away from it all, and George was so happy to be away from it all, but “You Never Give Me Your Money” is shot through with nostalgia for the past, sadness for the present, and a wistful melancholy for the future. While George’s and Ringo’s songs were snapshots of a moment in time, of how they felt at the precise moment they were writing the song, McCartney’s was a survey of all his conflicting emotions during this incredibly difficult time.

What follows is one of the greatest sustained album sides ever recorded, made all the more remarkable because most of the songs aren’t particularly good. They might have been good, or even great, given more time and effort, but the rest of Abbey Road is a collection of half-formed ideas for songs. Standing alone, most of these songs would be considered lesser Beatle efforts, toss-offs, and outtakes. Only two of the remaining eight songs break the two-minute mark. Confronted with the need to fill the rest of the album, and not having enough full songs to do it, with their interest level waning, McCartney suggested that they take their ideas and stitch them together to form one long suite of short songs. It was a brilliant idea that paid off big. Sure the songs are half-baked, but the reckless pace of what became known as either the “Abbey Road Medley” or, as it was commonly referred, “Side Two of Abbey Road” sweeps the listener along. The individual parts of the medley are unimportant (at least until “The End”), but the medley carries a rhythm and flow that essentially turn these disparate elements into one long song.

The real start of the medley is “You Never Give Me Your Money”, but that song is rarely considered to be the start since it’s a standalone song with a clear beginning, middle, and end. Yet as it finally drifts away in a wash of chiming guitars, “Sun King” slides in underneath, connecting the two pieces. “Sun King” is very close to being a full song, though the lyrics are very simple and the last refrains are a combination of Spanish, Italian, English, and gibberish. Lennon once referred to it as “a piece of garbage I had laying around”. But even these words sound marvelous with the Beatle voices locked in harmony. It’s an understated, slow song that provides the perfect introduction for what follows. “Mean Mr. Mustard”, with Paul resurrecting the fuzz bass he last used on Rubber Soul‘s “Think For Yourself” and John giving a great delivery of nonsense lyrics about a nasty man who hid money in his nose, picks up the tempo before crashing into the fast rocker, “Polythene Pam”, another snippet Lennon had in his back pocket. It makes more sense than “Mean Mr. Mustard”, as a straightforward tribute to an “attractively built” girl, but at just over a minute long it sweeps by so quickly that it barely registers. “Polythene Pam” then segues seamlessly into McCartney’s “She Came In Through the Bathroom Window”. It’s nearly two minutes long, and can rightly be seen as a standalone song (Joe Cocker covered it). It keeps up the pace of “Pam”, but is more structured and complete. It’s also lyrically more coherent, telling the tale of a fan who broke into Paul’s house and stole a picture.

There is the briefest of pauses (something I never understood) before “Golden Slumbers” begins with its quiet piano and soothing McCartney vocal, underpinned by George Harrison’s bass and a string section that swells and sighs behind the vocal melody with a melody all its own. The quiet interlude is brief, as McCartney starts belting out the chorus only to tone it down again for a repeat of the verse. Instead of the chorus repeating, “Carry That Weight” breaks in with a powerful horn flourish and a chorus of Beatle voices singing the lyrics as if the band members were a stadium full of soccer hooligans. Once again it’s McCartney commenting on the problems in the Beatles circle, evidenced by the return of the melody for “You Never Give My Your Money”, this time played by a horn section. The reprise of the earlier song crashes up against the main song’s climax before switching to the grand finale of “The End”.

The beginning of this finale is so much of a piece with “Carry That Weight” it could easily be seen as a continuation. Both songs are loud, bracing rockers; the anthemic “Boy, you gotta carry that weight a long time” vocal blends seamlessly into McCartney’s raw-throated “Oh yeah!/All right!/Are you gonna be in my dreams/Tonight?” that kicks off “The End” before sliding into the most unlikely thing one would expect on a Beatles album: a drum solo.

Ringo hated drum solos and had to be convinced to play one. Even here, given the chance to flail around like so many drummers do, Ringo chose to serve the song. The solo is brief, uncomplicated, musical, rock-solid, and unwavering. It’s the perfect Ringo vehicle, with none of the usual histrionics one expects from drum solos. As the solo ends, there’s a brief intercession with the band banging out chords and chanting “Love you!/Love you!” before segueing into the next least likely thing you’d expect to hear on a Beatles album arrives: a guitar duel. McCartney, Harrison, and Lennon (in that order) took two bars apiece, rotating three times, to cut heads one last time. Recorded live with the three of them playing and, according the the engineer Geoff Emerick, appearing ecstatically happy, the solos are perfect representations of their musicianship. McCartney’s solo is fluid and fast, complex, but musical. Harrison’s solo sounds more structured, but is equally facile. Lennon once said that as a guitarist he “wasn’t that good, but I can make it howl”, and he does so here. His chugging, distorted chording and triplets add just the right note of chaos to the structure. The solos build in intensity, a rock band firing on all cylinders before abruptly ending and giving way to a simple piano motif.

And in the end

The love you take

Is equal to

The love you make

It’s Paul sendoff to the band, and a last piece of advice for a tumultuous decade. The vocal, punctuated lightly with a three-note George guitar lick, ends with a huge buildup of strings and brass, McCartney’s breathy “Ahh”, and Harrison’s majestic guitar.

It’s really pretty amazing that collection of gestating song ideas, strung together, could provide a climax as cathartic as the final chord of “A Day in The Life”, but that is what happens here. Broken into their individual elements, only “The End” and, maybe, “Sun King” and “She Came In Through The Bathroom Window” hold up as complete entities. Taken as a whole, the sum of the parts is gloriously transcendent. The parts swirl, ebb, flow, crash, live, and breathe as a unique organism, and the medley remains one of the greatest moments in the Beatles recorded history, and elevates Abbey Road from the level of merely excellent to being considered one of their best albums.

And then…

Her Majesty’s a pretty nice girl

But she doesn’t have a lot to say

Her Majesty’s a pretty nice girl

But she changes from day to day

I wanna tell her that I love her a lot

But I gotta get a belly full of wine

Her Majesty’s a pretty nice girl

Someday I’m gonna make her mine, oh yeah

Someday I’m gonna make her mine

Grade: A+

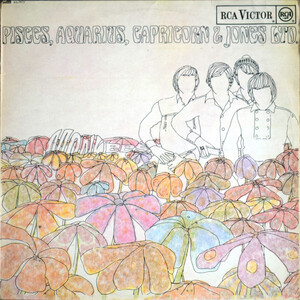

It’s an easy mistake to make, to judge The Monkees by their hit singles without ever diving any deeper. After all, it’s not like they were a real band driven to make artistic statements over the course of an LP. But easy or not, it’s a mistake. In fact, the Monkees albums are a virtual treasure trove of potential hits; with a band constructed to be a hit machine, virtually all of the songs that were given to them were viewed as potential singles, and the songs written by the band members were their attempts to break the stranglehold the producers held over their product.

It’s an easy mistake to make, to judge The Monkees by their hit singles without ever diving any deeper. After all, it’s not like they were a real band driven to make artistic statements over the course of an LP. But easy or not, it’s a mistake. In fact, the Monkees albums are a virtual treasure trove of potential hits; with a band constructed to be a hit machine, virtually all of the songs that were given to them were viewed as potential singles, and the songs written by the band members were their attempts to break the stranglehold the producers held over their product.

After Bridges to Babylon, the Stones became an almost endless touring machine. In 1998 they released the live No Security album, and followed that up with a double CD Live Licks in 2004. They also started repackaging their older material. The singles from their early years until 1971 were issued as multi-CD sets replicating the original vinyl releases, and the compilation Forty Licks was the first career-spanning set the Stones had ever released and included four new songs that don’t belong within a mile of a best of The Rolling Stones.

After Bridges to Babylon, the Stones became an almost endless touring machine. In 1998 they released the live No Security album, and followed that up with a double CD Live Licks in 2004. They also started repackaging their older material. The singles from their early years until 1971 were issued as multi-CD sets replicating the original vinyl releases, and the compilation Forty Licks was the first career-spanning set the Stones had ever released and included four new songs that don’t belong within a mile of a best of The Rolling Stones. In “The Hollow Men”, T.S. Eliot wrote the famous lines “This is the way the world ends/Not with a bang but with a whimper.” Eliot was writing about despair, but the lines could be applied to the implosion of the Beatles in 1969 and 1970. Since 1963 in Europe, and 1964 in America and throughout the world, the Beatles were the Sun in the musical sky, the immense star around which everything else orbited. They did it all, they did it first, and they did it best. They managed to grow in startlingly fast ways, while always increasing the size of their audience. They changed the musical landscape forever, and their impact is still felt today, nearly fifty years after the band broke up. Their legacy has proven immune to the ravages of time as every year a new generation of fans is created. There has never been anything like them in popular culture. There’s never really been anything even remotely close to them. The story is extraordinary.

In “The Hollow Men”, T.S. Eliot wrote the famous lines “This is the way the world ends/Not with a bang but with a whimper.” Eliot was writing about despair, but the lines could be applied to the implosion of the Beatles in 1969 and 1970. Since 1963 in Europe, and 1964 in America and throughout the world, the Beatles were the Sun in the musical sky, the immense star around which everything else orbited. They did it all, they did it first, and they did it best. They managed to grow in startlingly fast ways, while always increasing the size of their audience. They changed the musical landscape forever, and their impact is still felt today, nearly fifty years after the band broke up. Their legacy has proven immune to the ravages of time as every year a new generation of fans is created. There has never been anything like them in popular culture. There’s never really been anything even remotely close to them. The story is extraordinary.