Dissolution never sounded better than The Pogues. It seems almost churlish to ask how good the band would have been if they had tempered their wildly self-destructive tendencies and concentrated on the music. In his new memoir, Pogues accordionist and multi-instrumentalist James Fearnley asks the question whether it was Shane MacGowan’s headlong pursuit of oblivion that made him such a great artist. He doesn’t answer because there is no answer. Shane MacGowan was who he was, and never changed. The fact that he made it to the age of 65 before succumbing to his lifestyle is testament to the man’s constitution.

Dissolution never sounded better than The Pogues. It seems almost churlish to ask how good the band would have been if they had tempered their wildly self-destructive tendencies and concentrated on the music. In his new memoir, Pogues accordionist and multi-instrumentalist James Fearnley asks the question whether it was Shane MacGowan’s headlong pursuit of oblivion that made him such a great artist. He doesn’t answer because there is no answer. Shane MacGowan was who he was, and never changed. The fact that he made it to the age of 65 before succumbing to his lifestyle is testament to the man’s constitution.

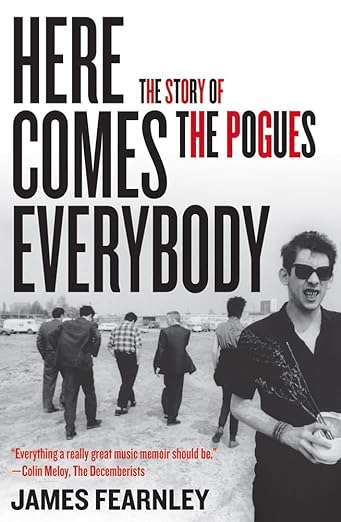

Just as any biography of The Doors quickly becomes a book about Jim Morrison, there’s no getting around the fact that the story of the Pogues is the story of Shane. Even though Fearnley gives plenty of ink to the other band members, MacGowan is the North Star. Even the cover of the book features Shane standing at the forefront while the rest of the band is in the background with their faces turned away from the camera.

The story here starts with MacGowan’s and Fearnley’s pre-Pogues band, the tastefully named Nipple Erectors (or The Nips, for short). MacGowan had discovered punk rock in mid-1970s England, quickly becoming one of the main faces on the scene. You can see a young MacGowan in dozens of film clips and photographs documenting the rise of bands like the Sex Pistols. The Nips were a very generic pub rock band with punk aspirations. There was nothing particularly interesting about them, as can be heard in what few recordings there are. There was certainly no indication of what MacGowan and Fearnley would do next.

By synthesizing traditional Irish folk music with the intensity and drive of punk rock, MacGowan and Fearnley created something entirely new. It was a recipe that later bands like the Dropkick Murphys and Black 47 would take up, though none of those bands came close to the gorgeous lyricism of the Pogues. The later bands took the wrong lessons, substituting ham-fisted party anthems and rebel songs for the more literate poetry that the Pogues, at their best, provided.

Fearnley is an excellent writer. It’s clear that he had literary ambitions before music took him down a different path. He sometimes gets a little precious with the language (e.g., the weather isn’t mild, it’s “clement”), but he seems at times to be downplaying the role MacGowan has in the story. Every member of the band drinks an enormous amount, but the death spiral of MacGowan seems to come out of nowhere. He’s a heavy drinker one minute and completely out of control the next, as if there were no linear progression of his illness. The singer they fired in a Japanese hotel room while on tour seems to be a different animal than he had been up to that point. (His response to being fired: “What took you so long?”) There is some discussion about Shane’s degraded vocals as time went on, but the final album with Shane, Hell’s Ditch, is almost completely ignored as is the fact that the vocals on the album are slurred and sloppy. MacGowan’s strong, if not very pretty, tenor was gone by that time. Whether this was a conscious choice to downplay the band’s notoriety in place of the sublimity of the music is a question only Fearnley can answer, but the effect is somewhat jarring.

The Pogues were almost a living stereotype of an Irish band. Profane, hard-drinking, boisterous, but with the soul of poets and the blood of their ancestors coursing through their veins. They sang songs about drinking, and fighting, and of Ireland’s oppression by the English. Anyone who’s ever been to an Irish wake will recognize the setting of “The Body of An American”. They sang love songs that bordered on inexpressible beauty. It’s almost impossible to believe that lyrics for songs like “The Broad Majestic Shannon” or the simply beautiful “Lullaby of London” came out of a man who claimed to have not been completely sober since the age of fourteen. Impossible, at least, until you’re more familiar with some of the great Irish literature.

The Pogues continued after Shane was kicked out, including a stint with Clash frontman Joe Strummer leading the band, but it wasn’t the same and Fearnley skips that time entirely. This is really a memoir of his time with Shane, of the great music on Red Roses for Me, Rum Sodomy and the Lash, and If I Can Fall From Grace with God. It’s a sad story, as the final years of Shane’s life are. He died in 2023, after being confined to a wheelchair for eight years when a fall broke his pelvis. He was an unrepentant drunk right up until the end. But now that the drinks are gone what remains are the lyrics, and they are timeless…despite the profanity.

Fearnley’s book has its shortcomings, but it’s a great story told well. The Pogues story in all its rambunctious glory may be best told by someone not so heavily invested in the story. But until that book comes, this is a worthy addition to the bookshelf.