Two American icons. One great English poem by Rudyard Kipling.

Month: May 2010

Where The Action Is: Los Angeles Nuggets, 1965–1968

This is the fifth release in the Nuggets series from Rhino Records, and the second to focus on a small geographic area (the first was San Francisco). Where The Action Is focuses on the sound of Los Angeles, but the box set also represents the sound of barrel scraping. It’s not all bad, by any means. Much of it is really excellent but for the first time in a Nuggets box (and I have yet to listen closely to the San Francisco box), there is also a distressingly large amount of mediocrity and way too much material that can only be classified as junk.

The box starts well with the Standells rave up “Riot On Sunset Strip,” strong tracks from The Byrds, Love, The Leaves and, especially, Buffalo Springfield and Captain Beefheart. Excellent songs from the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band (“If You Want This Love Of Mine”) and an extraordinary version of “Take A Giant Step” by the Rising Sons are also highlights, while the Association turns in a solid performance of Dylan’s “One Too Many Mornings.” These songs, and others, make the first disc of Where The Action Is a pretty stellar compilation. The sound is Nuggets-y garage rock, the performances inspired, and the songwriting generally good.

Disc One also demonstrates one of the problems with the box. The inclusion of Buffalo Springfield’s “Go And Say Goodbye,” Love’s “You I’ll Be Following,” and The Doors’ “Take It As It Comes” serve to make much of what else appears sound second-rate. The biggest problem is that, beginning with Disc Two, much of what appears is second-rate.

Frank Zappa once said that the “freaks” of Los Angeles were much weirder and wilder than the more famous “freaks” of San Francisco. That may be true, since Los Angeles was home to people like Zappa, Beefheart, Jim Morrison, Arthur Lee, etc. But Los Angeles is also a city that is built on dreams of stardom. When the Mamas and Papas sang of “California Dreamin'” they were headed to Los Angeles, not the hippie mecca of Frisco. Because Los Angeles is so focused on stardom, the industry there is more likely to be geared towards artificiality, and much of Where The Action Is sounds like it was cooked up in a board room by movie moguls looking to get into the music business.

Here come the phonies: Sonny and Cher, The Humane Society, The Others, The Velvet Illusions, Limey And The Yanks, etc. Way too much of this box sounds like the theme songs to ridiculous 1960s teen exploitation movies. Close your eyes during the annoying “Hippie Elevator Operator” and you can see the go-go dancers as the movie credits splash onto on the screen. Jan and Dean’s “Fan Tan” sounds like a TV commercial for chewing gum…simply awful. The Garden Club’s “Little Girl Lost And Found” is a shameless Monkees rip off. That’s right…a Monkees rip off. Worst of all is Dino, Desi, and Billy’s “The Rebel Kind,” an ode to rebellion that is so lifeless and pale it makes “You Light Up My Life” sound like “My Generation.”

There’s enough good and great material on here for a solid 2-CD set, but spread over four discs the flaws really stand out, and it doesn’t help to have included great material from the truly great bands. Near the end of Disc Four, wedged between the near parody of psychedelia “The Truth Is Not Real” (Sagittarius) and Barry McGuire’s “Inner-Manipulations,” is “You Set The Scene.” This song, the closing number from Love’s epic Forever Changes album, is so much better than anything else in a four-disc radius that it mercilessly crushes the competition. The effect is not unlike listening to a sampling of Merseybeat numbers from Billy J. Kramer and Gerry and the Pacemakers, and dropping the Beatles’ “A Day In The Life” in the middle. It’s simply not fair. Like Bambi vs. Godzilla unfair.

And that’s the striking thing about the box. By including numbers from bands like Love, the Doors, Beefheart, Buffalo Springfield, the Byrds, and the Beach Boys, the flaws of the other bands become so much more evident. Those great bands were real bands and had both sound and an artistic vision. They may have been looking for stardom, but they were first, and foremost, creative people. Too much of the rest of the box is people who have the sound, but no vision. It says a lot when the Monkees come across as one of the more “real” bands, because while they may have been made-for-TV they didn’t sound like they were made for TV. Indeed, the Monkees are represented here by the early Moog Synthesizer experiment piece “Daily Nightly,” an extraordinary Mike Nesmith original song. Too much material on this box, especially on Discs Two and Three, sounds like what movie and TV producers believed the kids of the day would enjoy. Where The Action Is sounds like Los Angeles: 40% real talent, 60% plastic.

Grade: B-

The Beatles: Please Please Me

It’s one of the most exhilarating openers in the history of rock and roll. Usually, count-ins are left on the cutting room floor since they serve no purpose for the listener and are not actually part of the song, but who would even want to imagine “I Saw Her Standing There” without Paul McCartney’s “One, two, three, faah“? Even after all these years, that simple count-in is enough to get the blood flowing. All of the excitement and sheer joy that were hallmarks of the early Beatles are present in those two seconds before the actual music even begins. The fact that it directly leads into one of the greatest of all early Beatle songs is just icing on the cake.

The Please Please Me album was intended as a moneymaker, benefitting from the moderate success of the first Beatles single, “Love Me Do” and the huge success of the #1 followup, “Please Please Me.” In 1963 albums were done strictly to cash in on the success of singles, which was the primary market for music (strangely, much like it is again today in the world of iTunes). Most rock “albums” were dreadful affairs…a hit song or two surrounded by filler that was chosen by a band’s producer or manager. Maybe there would be a few original songs thrown into the mix (especially if you were a particularly good songwriter like Brian Wilson, Buddy Holly, or Chuck Berry), but an enormous amount of the material for these early rock albums were either covers of earlier hits or new material produced by professional songwriters. There are exceptions, of course. Elvis Presley’s first RCA album was simply killer, and Presley was good enough to bring something special to even the most mundane songs that were forced on him, but that was still the exception to the rule.

A quick cash-in was certainly EMI’s intention when they agreed to let the Beatles release a full-length LP. But the Beatles were different, and their producer, George Martin, was different, too. The Beatles were perfectionists and incredibly headstrong. There would be no covers of “Old Shep” or “Blue Moon” for them. It’s not that they disliked those songs, it’s simply that they felt those songs weren’t right for them.

One of the end results of this band personality was that the Beatles refused to do anything that they felt was second rate. There would be no quick cash-in LPs…each song must be as good as the single. They wanted their fans to have 14 songs of outstanding quality, rather than two great singles (four songs) and 10 pieces of filler. In this sense, the Beatles helped to invent the rock album. (In 1963 in America, Bob Dylan was making a similar argument which led to the flawless The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, but he was still operating in a folk milieu.)

Please Please Me is not a great album when you compare it to what the Beatles would do later. When you compare it to what was being passed off as rock music in 1963, it was a lightning bolt straight to the heart of the Brill Building.

John Lennon and Paul McCartney had been writing plenty of songs, but the first album still contains many covers. The full blossoming of Lennon and McCartney’s brilliance was still to come. What this album provides the listener is the invaluable service of hearing what a typical set at The Cavern Club must have sounded like. Recorded in approximately 10 hours, Please Please Me is the Beatles racing through the best of their live show: roaring originals and smartly chosen covers of songs the band chose, not some record company or studio head.

After the opening cannon shot of “I Saw Her Standing There,” almost anything else would pale in comparison. “Misery” is a Lennon/McCartney original, and it’s a standard rock and roll number, circa 1963. The rhymes are simple, almost childish: “me/see/be/misery.” But even on this number the chorus soars when Lennon starts singing the ascending line “I’ll remember all the little things we’ve done,” enunciating each syllable as if the world depended on it, followed by a descending piano lick and the ascending “She’ll remember and she’ll miss her only one” and then the despondent tag of “lonely one.” Sure it’s an early song, and owes a great debt to Buddy Holly, but the voices lift the song over the somewhat flat music and transform it into a promise.

The songs the Beatles chose to cover were invariably well-chosen. One gets the feeling that they chose their covers not because they liked the songs, but because they felt they could bring something to the songs that hadn’t been heard before. Arthur Alexander’s “Anna (Go To Him)” has always been one of the great Beatle covers. Lennon’s voice is all pathos and the instrumentation is sublime. But here again, on the chorus when Lennon’s voice starts breaking against the rocks and McCartney and George Harrison start their wordless, Jordonaires-style backing vocals, the song becomes more than what the songwriter himself achieved.

From Carole King and Gerry Goffin comes “Chains” which features a harmony vocal on the chorus before George takes over for the verses. It’s a good number, but nothing special. But even here, the sound is extremely unusual for rock and roll because it sounds like an integrated group. This continues with “Boys,” a girl group number by The Cookies. Aside from the odd idea of a boy (Ringo Starr) singing about “boys/what a bundle of joy!” this is the fifth song on the record and the fourth lead singer. This idea of the “band” as a “group” is highlighted by Ringo’s exhortation “Alright, George!” before Harrison plays the guitar solo. What often goes unnoticed is that at this early stage, it can be credibly argued that Ringo’s homely singing voice is actually better suited for rock and roll raveups like “Boys” than George Harrison’s. Harrison later developed into a superb singer, but at this point his voice is all Liverpudlian teenage warbling. He seems unsure of himself, where Ringo is ready to just let fly.

They return to Lennon/McCartney originals with the “Please Please Me” single, starting with the B-side, “Ask Me Why.” It’s not a particularly good song, a bossa nova-style number with a solid, if unspectacular, hook. There’s a very real feel to the song in the vocals. Listen to Lennon’s voice crack when he tries to hit the high note on the “my happiness still makes me cry” line at 0:30. Throughout the song Lennon’s voice is, to be charitable, rough.

“Please Please Me” picks up the pace with one of the early examples of a great McCartney bass line pumping through the song, underlining Lennon’s blues-inspired harmonica, and the harmony vocals that raise the song above the ordinary. The lyrics are a cleverly disguised plea for oral sex, taking a subject that was certainly taboo on the radio and bringing it to #1 on the pop charts.

By the time the first Beatle single, “Love Me Do,” kicks off side two, it already sounds primitive. The lyrics are simplistic, on a par with any moon/June/spoon song, but the song contains a great harmonica solo and a captivating vocal tradeoff between Lennon on the verses and McCartney on the title of the song. There’s really nothing special about the song and if the Beatles had not gone on to be the Beatles, it’s likely that the song would have drifted into obscurity.

“P.S. I Love You” is McCartney’s tribute to Buddy Holly (“I love you/Peggy Sue”). It’s another slight song, but features really nice harmony vocals from Lennon and a very nice chorus. “Baby, It’s You” is a solid cover of a Burt Bacharach song. Clearly Bacharach was writing songs at a much higher level than Lennon and McCartney at this time. From a structural perspective, it’s one of the best songs on the album, and features a great Lennon vocal and one of those sublime George Harrison solos that mimics the melody.

Harrison takes another unconvincing lead vocal on “Do You Want To Know A Secret?” Lennon’s and McCartney’s “Doo dah doo” backing outshines the lead, and the song sounds pretty dated, but it’s still a fun listen with the band providing a sympathetic backing to Harrison’s scouse-infused vocals.

Strangely, “A Taste Of Honey” was one of my favorite Beatle songs when I was 10 or 11 years old. I’m not sure why I gravitated to this track, but the melody is superb and the vocals (McCartney on lead, Lennon on backing and harmony) are never less than excellent. The song had been kicking around England for a couple of years at that point, first as an instrumental and then with vocals, so when the Beatles recorded their version it was already on the charts.

“There’s A Place” is the final original track and it’s fascinating. The music is very straightforward and not all that interesting despite another solid bass line from McCartney, but the lyric is very unusual. Predating Brian Wilson’s “In My Room” by a few years, and predating the whole “transcendental meditation” craze by several years, here was Lennon singing about retreating into his own head: “There’s a place/Where I can go/When I feel low/When I feel blue/And it’s my mind.” That wouldn’t be all that out of place on “Tomorrow Never Knows,” but it shows up here in 1963, tacked in between a pop standard and a cover of a popular dance tune.

It is this dance tune that provides one of the great highlights of the early Beatles. The movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off made this song into a hit again in the mid-1980s, and the Beatles Anthology film includes about a hundred live versions of this song so, for me at least, it’s a little overdone. But there’s no mistaking the raw power behind “Twist and Shout.” Coming at the end of the album, sung in one full take by a shirtless, raw-throated Lennon at the end of a grueling 10-hour recording session, “Twist and Shout” is less an invitation to dance than it is a blast of pre-punk aggro rock. The ascending backing vocals from McCartney and Harrison blend with Lennon’s howl, punctuated by great drum fills from Ringo, to create two and a half minutes of rock aggression, ending the album with the same tone with which it begins. Those final seconds, where the music comes crashing down and someone (Lennon? McCartney?) manages one last defiant “Yeah!”, nail the lid on the album, and also close the door on 1950s and early 1960s-style rock and roll music. Even here, though, it is worth comparing McCartney’s formalized raveup “I Saw Her Standing There” with Lennon’s primal transformation of an Isley Brothers song. While both songwriters would later prove more than capable of working in the other’s wheelhouse, the division between the more formal McCartney and the more anarchic Lennon was already in place.

Please Please Me is the sound of the Beatles working with their influences, supremely confident in their abilities as a band, but still somewhat unsure as songwriters. From this point on, the growth exhibited by the band would be unparalleled in modern music.

Grade: B+

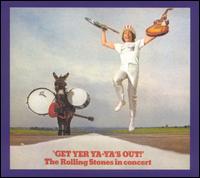

The Rolling Stones: Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!

In 1969, the Rolling Stones went where the Beatles feared to tred: back to the concert stage. The Stones hadn’t toured in three years (a lifetime back then), so the shows were greeted as the return of conquering heroes. The fact that the Stones were also riding on the enormous wave of both Beggars Banquet and Let It Bleed helped considerably. They had just released their two best albums to that point, and the technology and their audience had matured to the point where they could actually be heard in the concert halls.

The 1969 tour is considered by many Stones fans to be one of the best they ever did (the 1972 tour usually gets the #1 ranking), but the entire tour was completely overshadowed by the final show, at a little place we like to call Altamont, where a fan named Meredith Hunter pulled a gun in front of the stage and was subsequently knifed and beaten to death by the Hell’s Angels as the Stones looked on. The murder at Altamont, enshrined forever in the magnificent movie Gimme Shelter, cast a pall over the Stones that lasted for years.

What gets lost in the tale is just how good the rest of the tour was. This era was the peak for the band both as a recording unit and a live band. The extra musicians, blow-up phalluses, giant inflatable women, football jerseys, etc. were still years away and on the stage was a young band with a lot to prove.

The Stones had released an earlier live album called Got Live If You Want It, but that was a poorly recorded travesty where the band was largely drowned out by the screaming of teenyboppers. The album for the 1969 tour, Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! The Rolling Stones In Concert was an entirely different beast.

It is on the very first track where the Stones used a delay effect of over-lapping introductions to announce themselves by the title that would stick: The Greatest Rock and Roll Band In The World. From there the band launches into an incendiary take on “Jumping Jack Flash” that hits all the right notes for a live rock album: it’s looser than the studio version and the guitars especially have even more muscle.

“Carol,” one of two Chuck Berry covers, is a nice reminder that the Stones of 1969 were not that far removed from the Stones of 1965. That loose vibe, pressing up against but never crossing the border of sloppy, is fully evident as Keith rips into a great solo that would make Berry proud. “Little Queenie,” the second Berry cover unearths a little-known gem and provides perhaps the definitive take on the song. Both of the Berry songs are helped enormously by the boogie-woogie piano of the “sixth Stone,” Ian Stewart. His piano runs on both songs rival those of Berry’s great sideman, Johnny Johnson and give Keith a solid foundation for his guitar solos to achieve orbit.

From Banquet comes the salacious “Stray Cat Blues,” slowed down and raunched up even more than the malevolent studio version. The 15-year-old jailbait of the studio version is now a downright twisted 13-year-old. One of the things that sets this version apart from the studio version is Mick Taylor, who steps up throughout the album as the only true virtuoso to ever play in the band. Taylor’s genius is a magnificent counterpoint to the rawness and earthiness of the rest of the band. In many ways such a combination of prodigy and guttersnipes shouldn’t work, but it does. This is the first Stones album on which Taylor plays on every song, and he is the unsung hero throughout, along with the indispensable Charlie Watts.

The slide guitar Taylor plays on “Love In Vain” counters Keith’s delicate picking and lifts the songs above the more gentle version on Let It Bleed. Where Robert Johnson’s blues get a fantastic, acoustic reading on the studio album, it is this live, electric version that reaches deep into the heart of the Delta.

“Sympathy For The Devil” gets a radical overhaul, from the slow samba that graced Beggars Banquet to a sped up, raw blues with a dueling Richards/Taylor solo that nearly blinds the listener with brilliance. Bill Wyman also nearly steals the show here with his busy, sinister bass rumbling throughout the song. While it lacks the classic status of the studio version, this live version is hotter than a flamethrower. And it wouldn’t be complete without the plaintive cry from a girl in the audience requesting “‘Paint It Black’…’Paint It Black’…’Paint It Black’, you devils!” just before the chugging guitar introduces “Sympathy”…a live album moment so iconic that the Stones sampled it on their 1990 live disc Flashpoint as a joke.

Also sped up and raunched up is the already over-the-top “Live With Me.” One of the highlights of Let It Bleed, the live version is one of the highlights here. Mick Taylor simply owns the song, and Watts shines brilliantly throughout. It’s ramshackle and rough, but that’s what makes the song so compelling.

In contrast to most of the songs, “Honky Tonk Women” gets slowed down and put in touch with its blues roots. This is the version that really sounds like it belongs in a small, Southern honky-tonk, played on a stage hidden behind chicken wire. The studio version of the song is classic Stones, but this version sounds like it’s straight from the swamp.

The album closes with an extended, fully electric version of “Street Fighting Man” that Taylor dominates. It’s downright filthy compared to the studio version, and once again the Stones slow the song down a notch in order to increase the power behind the music. Where the studio version was all treble, with the acoustic guitars pushed into the red and flourishes of sitar providing an odd touch, this version is just plain mean…bottom-heavy, with Taylor’s lightning bomber runs soaring over Keith’s scorched earth rhythm.

Of all the songs on the album, it is the final track of side one that provides the centerpiece of the album, as well as creating a character for Jagger to inhabit with the same intensity that his London rival Roger Daltrey was inhabiting Tommy on stages at the same time. “Midnight Rambler” was a good, but anemic, track on Let It Bleed. On Ya-Ya’s it is all blood and blues, a truly harrowing performance that lets Jagger play the part of a sociopathic murderer with great conviction. Live, the song becomes so much more than it was on Let It Bleed that it became the standard version of the song for Stones fans. Forever after, when the Stones played “Rambler” it was the Ya-Ya’s version they trotted out. From the extended harmonica solos to the wicked guitar bump-and-grind of the slowed, thunderous middle section, this version helped solidify the aura of “evil” that had surrounded the Stones since the baleful video they made to promote the “Jumping Jack Flash” single.

The dirty little secret of live albums is that most of them aren’t very good. Most of them are just live versions of the band’s greatest hits, played with a great deal of professionalism and not a whole lot of passion. It is passion that makes a live album worth hearing, and there is plenty of it on Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! As live albums go, it is much more than a souvenir from the 1969 tour, it is an essential part of the Stones discography and one of the greatest live albums ever released, opening the door between the Stones of the 1960s and the band they would become in the 1970s.

Grade: A+

The Rolling Stones: Let It Bleed

The magnificent triumph that was Beggars Banquet had redefined the Stones as a serious rock band, as distinguished from their earlier incarnations when they were unsure whether they were rock, blues, soul, or psychedelic. The followup album, 1969’s Let It Bleed, extrapolated the themes from “Sympathy For The Devil,” “Street Fighting Man” and “Stray Cat Blues” and further clarified the band’s identity. Sinister, druggy, decadent, licentious…these are now well-established views of the Stones, but at that time it was a revelation.

The magnificent triumph that was Beggars Banquet had redefined the Stones as a serious rock band, as distinguished from their earlier incarnations when they were unsure whether they were rock, blues, soul, or psychedelic. The followup album, 1969’s Let It Bleed, extrapolated the themes from “Sympathy For The Devil,” “Street Fighting Man” and “Stray Cat Blues” and further clarified the band’s identity. Sinister, druggy, decadent, licentious…these are now well-established views of the Stones, but at that time it was a revelation.

At a time when the Beatles were exhorting everyone to come together, and the Youngbloods were advising us all to smile on our brother, the Stones emerged with a more realistic and darkly visionary look at the Sixties. The Stones had briefly bought into the psychedelic movement with all of its silly hippie nostrums, but it never suited them. Let It Bleed was the antithesis of the hippie movement. “Everybody get together/Try to love one another/Right now,” sang Jesse Colin Young in one of 1969’s biggest hits. The Stones countered with “Rape and murder/It’s just a shot away.”

If music can truly be described as sinister, it is the music that opens the leadoff track, “Gimme Shelter”: the lightly picked guitar, the scratched percussion, and those oh-so-haunting “ooohs” that sound like beautiful demons enticing you into their lair. “A storm is threatening,” sings Jagger in one of the best vocals of his career. “War is just a shot away,” and over the course of four and a half minutes the listener experiences nothing less than the soundtrack to the apocalypse. From the fire sweeping down the streets like a red coal carpet, to the image of a mad bull that has lost its way, to the life-threatening floods, “Gimme Shelter” paints a picture that is downright terrifying. Add in the chorus and Merry Clayton’s brilliant vocal about rape and murder, and the effect is both beautiful and brutal. All is not lost, though, as Jagger reminds us that “love is just a kiss away.” The music matches the lyrics, grinding and vicious. Other leadoff tracks on other albums may be as good, but the opening salvo on Let It Bleed has never been surpassed.

Perhaps trying to mimic the pace of Beggars Banquet, “Gimme Shelter” is followed by the acoustic/slide blues of Robert Johnson’s “Love In Vain.” With fantastic mandolin from Ry Cooder, the song is one of the best Stones blues covers, with Charlie Watts laying down a solid slow shuffle beat.

“Country Honk” follows and it’s a misstep. The third song is a country pastiche, again following the pace of Beggars Banquet. Where “Dear Doctor” worked on every level, the countrified version of the earlier single “Honky Tonk Women” doesn’t quite succeed. It’s not a total failure, and it’s certainly listenable, but it’s an embarrassment compared to the magnificent single which was inexplicably left off the album. Supposedly influenced by Gram Parsons, who had befriended Keith Richards, “Country Honk” lies lazily on the turntable. The lyrics were tweaked slightly, and the music is entirely different from the single: a light acoustic strumming and a down home country fiddle from Byron Berline give the main punch of the song, which is otherwise notable for one reason only: it is the first appearance of Mick Taylor on record with the Stones. Brian Jones, by this time, was dead though he turns up (barely) on two songs from Let It Bleed, and his replacement had not yet been fully cast when the album was recorded.

Side one continues with a fierce bass line played by Keith Richards. “Live With Me” is the “Stray Cat Blues” of Let It Bleed. Blessed with riches and success beyond their wildest dreams, Jagger proves that he’s still the decadent guttersnipe he always claimed to be. The song is an invitation to a woman who Jagger seems both to want to employ as a nanny for a “score of harebrained children” and also take to his bed. “You’d look good pram pushing/Down the high street,” Jagger sings. “Don’t you wanna live with me?” Jagger’s home needs “a woman’s touch” and comes across as an X-rated version of Upstairs, Downstairs. The cook is “a whore” who is apparently making it with the butler in the pantry and stripping to the delight of the footman. The Lord of the Manor, meanwhile, has “filthy habits” and a friend who shoots rats and feeds the carcasses to the geese on his property. It’s quite an invitation. In many ways, this is part two of “Sympathy For The Devil.” It’s the same character, different scenario.

Musically, “Live With Me” is a tough rocker, with Keith’s bass leading the way through the verses with stabs of guitar from Keith and Taylor and piano from Nicky Hopkins and a rock steady beat from Charlie who rarely deviates except to punctuate with brief fills in the chorus. This song is also notable for being the first time the Stones recorded with Bobby Keys, who plays the great saxophone solo.

The title track, “Let It Bleed” closes out the first side. It’s considered a classic Stones song, and rightly so. The lyrical themes of drugs and decadence are solidly in place, with Jagger slurring his tale of junkie friendship. Or perhaps it’s more subtle than that: Jagger is not singing to or about another person, he is singing about drugs, and how they begin as a friendship, and end badly. The drug dealer says “You can lean on me” and appears in the form of a beautiful woman. “My breasts will always be open/Baby, you can rest your weary head right on me/And there will always be a space in my parking lot/When you need a little coke and sympathy.” But the drugs have a dark side: “You knifed me in that dirty filthy basement/With that jaded, faded, junkie nurse/Oh, what pleasant company!” The lyric changes from the friendly “we all need someone we can lean on” to the considerably darker “we all need someone we can feed on.”

Keith plays a tasteful slide guitar throughout, and Ian Stewart plays great boogie-woogie piano while once again it is the acoustic guitar that provides the steady rhythm. “Let It Bleed” may go on a little long, and it lacks the visceral punch the lyrics deserve, but it’s still an extraordinary song of drugs and dissolution.

From drugs to murder, side two opens with “Midnight Rambler,” inspired by the tale of the alleged serial killer Albert DeSalvo, aka The Boston Strangler. In the song, the killer is nearly a supernatural presence, more akin to Candyman than the Boston Strangler. Jagger’s harmonica provides the musical hook, and while Keith’s main guitar riff and slide guitar are top flight, the song doesn’t really work in this setting. “Midnight Rambler” is considered one of the great Stones songs, a true classic, but for most listeners the definitive take is the live version from Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! The studio version is too long and not particularly interesting. Charlie rides his usual steady beat, but the song never really achieves liftoff, unlike the transcendent live version that was released the following year.

What follows is one of the best Keith Richards performances on record. “You Got The Silver” is one of the three best Keith vocals ever recorded (for what it’s worth, the others are “Happy” and “Before They Make Me Run”). It is the first time he sings lead on an entire track, and his vocal simply shreds Jagger’s heavily bootlegged version. “You Got The Silver” is a modern country blues, the likes of which the Stones started crafting on Beggars Banquet. The great slide and country-fueled rhythm acoustic meet with Nicky Hopkins’ stately piano and Charlie’s simple, sparse, and elegant drums to make one of the Stones’ finest ballads, with Keith’s weathered vocals providing the icing on the cake.

Bill Wyman leads off “Monkey Man” on the vibes, before the rest of the band comes crashing in, with Keith’s raunchy guitar taking the pole position and using the same sinister tone he used on “Gimme Shelter.” The lyric is a bit of nonsense, more druggy decadent myth-making from Jagger, but the music is astonishing. Charlie rolls around the drums, and Nicky Hopkins once again proves himself the best session keyboardist of his time, his duet with Wyman’s vibes underpinning a Keith slide riff that starts tentatively and then suddenly shoots into orbit.

The album concludes as it began, with a seminal statement on the times. Released very late in 1969, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” should be written on the tombstone of the Sixties. Opening with the London Bach Choir singing the first verse a capella before giving way to Keith’s strummed acoustic guitar and a lyrical French horn solo from rock’s own Forrest Gump, Al Kooper. When Jagger enters, backed only by the acoustic guitar, he seems to be standing before the crowd unclothed until he is lightly joined by Rocky Dijon’s percussion. Al Kooper’s descending piano runs herald the entrance of the band when, like a kick to the solar plexus, producer Jimmy Miller comes roaring in on the drums (Watts couldn’t get the piece, so Miller jumped in the drummer’s chair). Suddenly it’s all there: Keith’s stinging lead guitar lines sliding in and around the other musicians, with Kooper doubling on piano and organ, and Bill Wyman providing a rollicking bass line. Jagger surveys the Sixties and finds them wanting. In turn he looks at love, politics, and drugs and reaches the same conclusion about all of them: the Sixties dream was just a dream. Much more realistic than many of his musical peers, Jagger and Richards reach the conclusion that it’s not necessarily a bad thing not to get what you want, because you’ll get what you need.

Of the five album run that started with Beggars Banquet (four studio, one live), Let It Bleed is the weakest link. That says much more about the merits of the albums that surround it, however, and very little about any discernible lack of quality here. Let It Bleed is a flawed masterpiece, providing the jaded riposte to the way the Beatles ended the decade with “The love you take/Is equal to the love you make.” Flaws and all, it is essential listening.

Grade: A