For decades now, whenever some music magazine that’s staffed with old hippies (*cough* Rolling Stone *cough*) makes a list of the Greatest Albums of All Time (by which they mean the greatest albums since 1964), they invariably settle on The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band as the choice for number one. But a funny thing happened several years ago when VH1 created a list of the 100 Greatest Rock Albums. As voted on by critics and musicians, the number one choice was Revolver. Since then, Revolver‘s stock has risen sharply while Pepper’s has dropped.

The rise in Revolver‘s status coincides directly with the release of the album on compact disc in 1987 when, for the first time, the original version of the album was released in America.

Revolver was the last Beatles album to be eviscerated by Capitol Records, and was probably the most damaged aside from the movie soundtracks. The American version of the album was a hard-hitting classic, long considered one of the very best albums by the band. When the English version was released in America, it was a revelation. As great as the American version was, three of the best songs had been removed.

| U.S. Edition | U.K. Edition |

1. Taxman

2. Eleanor Rigby

3. Love You To

4. Here, There, and Everywhere

5. Yellow Submarine

6. She Said, She Said

7. Good Day Sunshine

8. For No One

9. I Want To Tell You

10. Got To Get You Into My Life

11. Tomorrow Never Knows

| 1. Taxman

2. Eleanor Rigby

3. I’m Only Sleeping*

4. Love You To

5. Here, There, and Everywhere

6. Yellow Submarine

7. She Said, She Said

8. Good Day Sunshine

9. And Your Bird Can Sing*

10. For No One

11. Doctor Robert*

12. I Want To Tell You

13. Got To Get You Into My Life

14. Tomorrow Never Knows

|

|

| *Released in America on the LP Yesterday…And Today |

What makes the song removal even more unfortunate was that all three songs were John Lennon’s. As a result, George Harrison is a stronger presence on the American version as the writer and singer of three songs while Lennon is relegated to the album closers on each side. This has the effect of making the album seem lopsided. Paul is here, there, and everywhere and George is hot on his heels, but Lennon gets only one song more than Ringo.

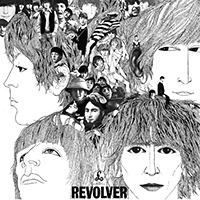

No discussion of Revolver should begin without mentioning the cover art. Designed by their friend from Hamburg, the artist and bass player Klaus Voorman, the front cover of the album took the mildly hallucinogenic cover of Rubber Soul and exploded it. In stark black and white, the Beatles appear as line drawings, with only their eyes and George’s lips looking like cut and pastes from photographs. The four heads take up the entire cover while old photos (including some from the back cover of Rubber Soul) and surreal comic versions of the Beatles that look like they were drawn by Edward Gorey appear in their hair. Some of the photos are stretched or distorted, all of them are odd in either appearance or placement: Ringo in an old-fashioned bathing suit, George in a safari hat, John looking like he’s grown a giant Amish-style beard, a younger Paul hiding behind the cartoon of his own ear. And the single word in all capital letters: REVOLVER. In all of rock music to this point there had never been an album cover even remotely this strange. On the back cover, below another all-caps REVOLVER and the significantly smaller words “The Beatles” is a black and white photo of the band in the studio, sitting together, looking at each other instead of the camera, wearing sunglasses.  If there’s a photo of a band where the group members look cooler than this, I’ve never seen it. This is the band in their “We’re The Coolest People On Planet Earth” phase (see also the videos for “Rain” and “Paperback Writer” from the same time period). The back cover of Revolver is one of the all-time great rock and roll photographs. The Beatles were looking less like the gear fab Mop Tops on Rubber Soul, but here they put that image behind them forever.

If there’s a photo of a band where the group members look cooler than this, I’ve never seen it. This is the band in their “We’re The Coolest People On Planet Earth” phase (see also the videos for “Rain” and “Paperback Writer” from the same time period). The back cover of Revolver is one of the all-time great rock and roll photographs. The Beatles were looking less like the gear fab Mop Tops on Rubber Soul, but here they put that image behind them forever.

If the cover didn’t prepare you with the idea that the Beatles were up to something new, the music sure did. Their first album, Please Please Me, kicked off with Paul’s exuberant “one-two-three-four!” and three short years later Revolver begins with George’s slurred, off-time and off-beat, slow count in on “Taxman”. This was clearly a different group. For starters, it was George who kicked the album off, with his strongest song yet, a withering protest against Britain’s outrageously confiscatory 95% tax rate. His songwriting at this point was floating in that rarefied air with his bandmates Lennon and McCartney. But the song was also unusual. The guitar was heavy and distorted, unlike any heard on a Beatles song before. The ferocious guitar solo, played by Paul McCartney, exploded out of the speakers and was designed to mimic the feel of Indian music, George’s latest passion. The song sounded both Western and Eastern: the instrumentation of one with the scales of the other.

“Taxman” (and, in fact, all of Revolver) is also a perfect example of why the early Beatles are best heard in mono, rather than stereo. Listening to the stereo of “Taxman” can be downright painful, especially on headphones. Virtually all the music except the tambourine and the guitar solo comes from one speaker. The mono version is louder, punchier, and fuller. It’s also a different mix: the very prominent tambourine comes in earlier in the mono version. This is true throughout the album. The mono mix is clearly superior, and is the version the Beatles were fully involved in creating (the stereo mix was done by George Martin with no input from the Beatles). Song endings are longer (“Got To Get You Into My Life”), sound effects are placed differently and are more abrupt (“Tomorrow Never Knows”), vocals sound fuller (“Eleanor Rigby”). Generally speaking, the Beatles are worth hearing in mono all the way up through the White Album; on Revolver the mono mix really shines.

Shortly after “Taxman” ends in a welter of guitar and righteous indignation, McCartney’s “Eleanor Rigby” tells the story of the lonely titular character and the equally sad priest who presides over her funeral. The story is told over a pummeling string section; no traditional rock instruments are used, and John and George are only present in the backing vocals. But where McCartney’s (and George Martin’s) use of strings on “Yesterday” was light semi-classical, the strings in “Eleanor Rigby” pound in a staccato fashion that sounds vaguely like Bernard Herrmann’s soundtrack to

Psycho. The strings are playing in the place of rock and roll instruments; “Eleanor Rigby” could be rerecorded with heavy electric guitars and still maintain the same vibe. The strings on “Yesterday” sweetened the song; here they hammer home the sadness. “Eleanor Rigby” was McCartney’s finest moment to this point, a direct response to the challenge posed by Lennon’s increasingly sophisticated lyrics on

Rubber Soul and to

Pet Sounds, the Beach Boys album that was changing the way rock music could sound.

McCartney’s presence on Revolver was amplified by Lennon’s absence on the US version, making it sound like Macca had taken control over the band. On the official release it was clear that McCartney had assumed co-leadership duties with Lennon. Prior to Revolver, The Beatles had been Lennon’s band. On Revolver, they became Lennon and McCartney’s band. Lennon’s first track on the album was “I’m Only Sleeping”, a hymn to laziness or, perhaps, the stupor of being under the influence. At this time, Lennon was smoking a lot of dope and taking LSD like it was candy. Both drugs are reflected on the track. Marijuana informs the lyrics about a man who doesn’t want to do much of anything except lie in bed, sleeping and watching the world go by. Acid informs the music by inserting backwards guitar into what is otherwise a conventional rock track. Throughout the song snippets of backwards guitar rise from the background before erupting in a solo. The tone of the guitar gives the song an Eastern feel but also a psychedelic edge. Lennon’s voice also sounds unlike any of his previous vocals. It’s identifiably Lennon but here he sings in a higher, more nasal, register that adds just a bit more of an edge to the song. By this point on the album, I’m sure more than one first time listener was asking what the band was doing.

The answer is that they were challenging themselves and their audience about what the definition of rock music could be. George’s second song was a nearly pure Indian raga called “Love You To”. It’s the best example of George’s blending of rock and raga. A heavily fuzzed guitar and subtle bass are subservient to Indian instruments, primarily sitar, tambura, and tablas, but it’s still readily identifiable as rock music. Much like “Eleanor Rigby”, “Love You To” is a rock song played by mostly non-rock instruments. Through it all, blended with the music is George’s vocal. He sings the song in a flat, almost monotone way that perfectly complements the music.

On Rubber Soul the Beatles started branching out beyond love songs. Songs like “Nowhere Man” and “Think For Yourself” were the first songs the Beatles had done that weren’t about love in a boy-girl relationship. On Revolver, there are only three love songs, including two of the best that Paul McCartney ever wrote. “Here, There, and Everywhere” may be McCartney’s finest moment as a balladeer. The lyrics are sentimental and sweet, but not cloying or obvious. Some of the lyrics are downright gorgeous: “changing my life with a wave of her hand” and the ingenious way he works in the words of the title show the significant growth in McCartney. “Here, There, and Everywhere” is the Beatles first love song for adults, and makes a nice companion to “For No One”, the heartbreaking love song on side two. Here, McCartney sings about the dissolution of a relationship in a similarly adult fashion. Here the story is not that of a relationship that is over, but one that is on life support. “In her eyes, you see nothing” sings McCartney in the album’s most devastating line. “She says that long ago she knew someone/But now he’s gone/She doesn’t need him.” While the obvious interpretation of the lyrics is that Paul is observing somebody else’s relationship and commenting on it, “For No One” has always seemed far too personally heartfelt to me. The fact that McCartney says it was written about an argument with his girlfriend, the actress Jane Asher, also makes it personal. When seen as a song about himself, the switch from second person to third person further emphasizes the alienation the lover feels as the love is pulled away from him. Without his love, the song’s narrator can only see himself from the outside: first as an involved character in his life story “you see nothing” and then, as the relationship ends, as a faceless and nameless “him”. In a style of music that is replete with songs about broken love, “For No One” is one of the best, a perfect marriage of lyrical and musical pathos. The French horn solo, first hummed by McCartney, transcribed by George Martin, and then played by Alan Civil, is one of the greatest moments on the record, capturing all the wrenching emotion of the lyric and translating it into music.

The third love song, “Good Day Sunshine” kicks off the second side of the album. It’s a far more straightforward number than most of those on the album. It could have fit well on Rubber Soul or even Help! but that doesn’t diminish its many charms. For starters, it’s one of the few songs on the album that can genuinely be called “upbeat”. It’s a happy tune, propelled by piano and McCartney’s extraordinary vocal. It’s one of those songs that is simply impossible not to like. If it sounds slight in comparison to the rest of Revolver, that’s because it is. But lightheartedness was always a part of the Beatles’ arsenal. For every “Tomorrow Never Knows” there’s a “Good Day Sunshine”; for every “I Am The Walrus” there’s a “Yellow Submarine”. Revolver was, for the Beatles, a heavy album in lyrical terms. Politics, drugs, loneliness, and death are all explored. “Good Day Sunshine” goes a long way towards pushing away the gloom of what could have been a very bleak album. As such, it is “Good Day Sunshine”, “Got To Get You Into My Life”, and “Yellow Submarine” that, as much as anything, make Revolver a Beatles album. The secret weapon of the Beatles (and almost any good band) was their sense of humor and fun. An album without those elements simply would not have worked as well. It is the very lightness of these songs that is what makes them so good. They stand on their own as great, fun songs but also leaven the album as a whole.

Still, if there’s a weak link on the album (and actually, there isn’t) it’s “Yellow Submarine”, a children’s song that puts The Goons into popular music while calling back to Spike Jones. Lennon always claimed that it was one of the most fun times he ever had in the recording studio, and it’s easy to see why. The song is filled with silliness and Lennon loved that type of humor, and the stories of the recording session include tales of Beatles roadie Mal Evans leading a conga line while banging on a bass drum and assorted EMI employees raiding the archives for sound effects that were then used with great abandon. “Yellow Submarine” is a classic Beatles song. To adult ears, it can be a little wearing. Ringo’s voice is…well, it’s Ringo’s voice, and the sing along chorus is a bit cloying after awhile. Still, there is a lot of fun in the song and it is essential listening for any child under the age of ten. The stories of the recording also prove a central truth of the Beatles: through their restless creativity and boundless energy, they were changing the way music was recorded. In stuffy EMI studios, where microphones had to be placed precisely and where the recording engineers wore white lab coats, the Beatles were anarchy unleashed. They challenged all the rules of the studio and, therefore, of recorded rock music. “Yellow Submarine” is a perfect example of that. In the studio the Beatles were free, while on tour they were prisoners. Recordings like “Yellow Submarine” went a long way in setting the precedent that studios could be used to do more than record, that they could be used to create. It’s a legitimate question to ask whether the Beatles would have felt the freedom to experiment like they did on “Strawberry Fields Forever” without first flouting convention on “Yellow Submarine”.

George appears in the spotlight for the third time with “I Want To Tell You”, a far more conventional rock song than his first two offerings. Or is it? In some ways “I Want To Tell You” is every bit as radical as Lennon’s songs on the album. The lyrical matter is about the difficulty of communication, and the music matches it. Strange chords, a discordant piano, the climax of Lennon and McCartney singing “I’ve got time” in a way that mimics an Indian raga. McCartney’s bass pounds the listener and George’s riff that slides in and out of the song is a winner. The riff was so good that Jimi Hendrix played it on the BBC before launching into a version of “Day Tripper”. When Hendrix tips his hat to your riff, you know you’ve got something special. The backing vocals from Lennon and McCartney are jarring, they underpin George’s lead vocal but are more strident and difficult. There’s an enormous amount of stuff going on in these two and a half minutes. Musically it’s far more complex than “Love You To” or “Taxman” yet it doesn’t seem that way when you listen. It’s only when the listener burrows into the song that the weirdness of it is revealed. While it sounds conventional on the surface, “I Want To Tell You” is Harrison at his most daring while playing in the confines of traditional rock music. His Indian-inspired songs may have sounded stranger to Western ears, but this is where he was truly experimenting with song structure.

John Lennon was the main songwriter for “And Your Bird Can Sing”, with some help from McCartney. The subject is very much a mystery as the words don’t really seem to make much sense. My best guess is that it was written as a joke to Mick Jagger about his girlfriend, Marianne Faithful. That was one of the rumors, at least, but what is one to make of “And your bird is green/But she can’t see me” or “When your bird is broken/Will it bring you down?” Lyrically it’s a slice of surrealism (charitably…it could just be nonsense) that comes across as silly. Lennon later criticized the song as one of his throwaway tracks, but Lennon was his own worst critic. Musically it’s another matter. The music on “And Your Bird Can Sing” is fantastic. The lead guitars, two locked in harmony played by George and Paul, lay a foundation on which you could build a city, and McCartney’s bass throbs in the background, providing another lead instrument deep in the mix. It’s another upbeat, hard rocking moment. Coming right after “Good Day Sunshine” on side two, it seemed to show a turn away the heavy vibe of the album before “For No One” brought back the darkness.

The four remaining songs on Revolver could not be more different, yet they all share one thing in common. The subject in all four songs was inspired by the same thing: the band’s increasing experimentation with mind-altering substances. McCartney’s “Got To Get You Into My Life” sounds like an upbeat, soul-style love song and there’s a reason for that. It is an upbeat, soul-style love song. The object of McCartney’s affection in the song is not a woman, though. “Another road where maybe I could see another kind of mind there,” Macca sings as if his heart was about to burst out of his chest. McCartney later admitted that the “you” in the song’s title and chorus was actually marijuana. Still, the lyric was disguised enough so that it didn’t raise suspicions among listeners or critics, and the song is so catchy and joyful that the music overwhelms the lyrics. Driven by a punchy and powerful horn section, with a short but very electric guitar solo, and McCartney raving in his Little Richard voice over the fade, “Got To Get You Into My Life” was more proof that the Beatles were no longer bound by the sound that had propelled them to the top of the charts. Anything they wanted to try was valid and their level of fame (and the money they brought in to EMI) ensured that they were given carte blanche. Revolver is nothing if not stylistically diverse: rock, pop, soul, raga, ballads, orchestration, psychedelia, and novelty songs all coexist seamlessly on one album that’s less than forty minutes long.

“Dr. Robert” was John’s ode to a physician who peddled a lot more than health. Originally inspired by a New York physician named Robert Freymann who was famous for providing amphetamines to his rich clientele, the final character in the song is probably a combination of several people, including John’s dentist (the man who first slipped LSD in John’s and George’s coffee at a house party). In a more innocent time like 1966, it’s possible to imagine that the song could be written off as merely a song about a doctor. With hindsight, the drug references are obvious. “Take a drink from his special cup”, “If you’re down he’ll pick you up”, “You don’t pay money just to see yourself”, “He helps you to understand” are all blatant allusions to drugs in the context of the song. “Dr. Robert” is “a new and better man”. The guitar, heavy and distorted, plays in short, choppy bursts under Lennon’s double-tracked vocals before the chorus abruptly shifts into a dreamlike harmonium and Lennon’s floating vocal of “Well…well…well, you’re feeling fine/Well…well…well, he’ll make you”. Again McCartney plays a stellar bass line that flows in the verses and ebbs in the chorus, providing a harmonic counterpoint to those choppy guitars.

It is the songs that end each side of the album that are the clearest indication that the Fabs were into something very new and very different. “She Said, She Said”, which closes side one of the LP, is a fairly accessible rock song, but the lyrics were something else entirely. Only a couple of years earlier John Lennon had sung about wanting to hold your hand. Now he was coming out of the gate with “She said ‘I know what it’s like to be dead/I know what it is to be sad’/And she’s making me feel like I’ve never been born”. The lyrics reflect a nightmarish party where the band and their guests were tripping on acid and the actor Peter Fonda kept trying to tell them a story of a near-death accident he had as a child. According to Lennon, Fonda kept walking up to him saying “I know what it’s like to be dead”, a statement that had the understandable effect of freaking out Lennon during his drug-induced trip. This was a pop/rock song that had lyrics like no other before it. There had certainly been songs about drugs and death before, but never in a context like “She Said, She Said”. For an audience that was not “turned on” the lyrics must have been completely baffling, yet the music was straightforward for the most part. The guitars were incredibly loud and sharp, bordering on shrill, and Ringo especially shines throughout the song. John sings in the same nasal voice that he used on “I’m Only Sleeping”. It’s both a thrilling record and an exhausting one. At the end of the song the listener can be excused for being puzzled, alienated, or confused. While accessible, the music was heavier than any other Beatles song except perhaps for “Papberback Writer”/”Rain”, the magnificent single that preceded Revolver by a couple of months. The vocal was John distorting himself and the lyrics were unrelievedly dark and mysterious. What makes it all the more alienating was that the song immediately follows the happy, jaunty “Yellow Submarine”, providing the first of the two greatest contrasting song segues in the Beatles’ career.

The greatest contrasting song segue in the Beatles’ career, maybe in the history of recorded music, is found on side two. “Got To Get You Into My Life” was a finger-snapping, toe-tapping, head-bobbing slice of happy music. The song that followed it…wasn’t.

When Bob Dylan toured England in 1966 he was visited in his hotel room by Paul McCartney. McCartney brought an acetate of a new Beatles song to play for Dylan. When it was over Dylan said, “I get it. You don’t want to be cute anymore.”

If there was a final nail in the coffin of the Mop Tops, and a first glimpse of what was to come, it was “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the concluding track on Revolver. Beginning with a harsh buzzing sound, the song takes every pop/rock song structure and abandons them. For the pop audience, this was something the likes of which had never been heard before. The only readily identifiable sound is Ringo’s drums, playing a repetitive pattern that never deviates, behind what sounds like seagulls flying overhead, harsh backwards guitar that rises and falls, menacing sound effects, calliope sounds, and swells of distorted keyboards and horns. Most of these sounds were either backwards or sped up, frequently both. With the exception of that hypnotic drum beat and a brief snippet of piano during the fade, there is no standard music at all on “Tomorrow Never Knows”. And floating above it all is Lennon’s voice: “Turn off your mind/Relax and float downstream/It is not dying” he sings. “Lay down all thoughts/Surrender to the void.” Even Lennon’s voice switches at the 1:30 mark. Suddenly he sounds a million miles away, his voice just another sound effect. “Play the game existence to the end/Of the beginning…” Lennon had told their engineer that he wanted his voice to sound like a thousand chanting monks on a mountain top, but the sermon here is about the mind expanding effects of LSD. The vocal effect was produced by running John’s voice through a rotating speaker (called a Leslie).

The “music” was pieced together by Lennon and McCartney, after Paul had played John tapes of avant-garde music that he’d been experimenting with. The buzz is based on Indian music, with the entire song being in the key of C, with no chord changes. The “seagulls” were sped up laughter The lyrics were inspired by a Timothy Leary book about The Tibetan Book of The Dead, with some lines lifted almost verbatim from Leary’s book.

The days of “She Loves You” and “I Want To Hold Your Hand” were officially over. “Tomorrow Never Knows” was an unsettling, trippy, avant garde music that, amazingly enough, still manages to be an accessible, likable song. Other musicians, most notably Frank Zappa, were working in this territory at the same time, and the Beatles themselves would revisit this style with “Revolution 9” on the White Album, but “Tomorrow Never Knows” manages to pull off the staggering trick of being both non-musical and rock music at the same time. Zappa’s sound collages were just that: there was very little that was musical about them. The Beatles had proven that even the most far out sounds can work not merely in a pop song, but as a pop song. In one burst of creative genius and throughout one album, they’d proved that the old rules no longer applied. The entire musical world was listening and wondering where the Beatles could possibly go from here.

Is this the greatest album of the rock era? There’s really no objective way of saying that. But any good collection of music from the second half of the 20th century is not complete without Revolver. It is one of the crucial building blocks on which the music of the past fifty years is based. Absolutely essential listening.

Grade: A+