In 1965, the squalling musical brat known as rock ‘n’ roll took its first steps to becoming the music that would dominate the rest of the 1960s all the way through the mid-1990s: rock. The transition wouldn’t really be complete until 1966, but the “new” music started the year before. The difference between the two forms, often referred to interchangeably, is stark. You could dance to rock ‘n’ roll, and the lyrics were usually pretty benign odes to teenage love and lust. It was the music of kids. Rock music, on the other hand, was heavier, noisier, lyrically expansive (love and lust were still the biggest topics, but of a somewhat less innocent nature). In folk music, Bob Dylan was expanding the vocabulary of lyricists everywhere. This wasn’t lost on the young rock musicians like the Beatles and the army of guitarists who followed in their wake.

The Byrds were the first to make explicit the connection between Dylan’s lyrics and wordplay and the beat laid down by the rhythm section of Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr. But in 1965 the Bard of Greenwich Village also made the connection when he laid down his acoustic guitar and brought in a heavily amplified backing band. The Beatles, too, made the connection in the opposite direction by using more acoustic instruments and using far more colors in their lyrical palette.

The new music in 1965 was heralded by six of the best albums of the 1960s. Since Dylan already had the words aspect of songwriting down to an art, it was his music that was most radically different. The Byrds were the perfected synthesis of the 1964 Dylan and 1964 Beatles. The Beatles, already restlessly inventive with their music, turned their attention to the words.

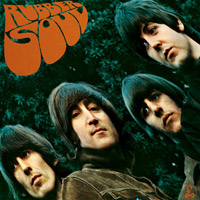

The fact that Rubber Soul, one of the best albums of all time, is only the second or third best album of 1965 is testament to the fact that Bob Dylan had just changed the landscape with the two masterpieces he released that year, Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited. The fact that Rubber Soul is a better album than the Beatles’s own Help! or the first two Byrds albums, Mr. Tambourine Man and Turn! Turn! Turn! is testament to just how great the Beatles were at this time.

The album was cannibalized for release in America, as usual, but in this case the album didn’t suffer too greatly. In some ways, it was strengthened.

| U.S. Edition |

U.K. Edition |

1. I’ve Just Seen A Face*

2. Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

3. You Won’t See Me

4. Think For Yourself

5. The Word

6. Michelle

7. It’s Only Love*

8. Girl

9. I’m Looking Through You

10. In My Life

11. Wait

12. Run For Your Life |

1. Drive My Car**

2. Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

3. You Won’t See Me

4. Nowhere Man**

5. Think For Yourself

6. The Word

7. Michelle

8. What Goes On**

9. Girl

10. I’m Looking Through You

11. In My Life

12. Wait

13. If I Needed Someone**

14. Run For Your Life |

*Originally released on the British LP Help!

**Released in America on the LP Yesterday…And Today |

It’s possible that my personal experience colors my opinion here. I grew up with the American LP and while the album is certainly not improved by losing John Lennon’s masterful “Nowhere Man” and George Harrison’s excellent “If I Needed Someone”, the fact is that “I’ve Just Seen A Face” belongs here. Lost in the middle of side two of the British LP Help!, this fantastic McCartney track, with its furiously strummed acoustic guitar rhythm and propulsive vocal, is the perfect first song for Rubber Soul, miles ahead of the surprisingly pedestrian “Drive My Car”. And while “It’s Only Love” is somewhat slight, musically it’s a perfect fit with the rest of Rubber Soul. The same can’t be said of the equally slight country pastiche “What Goes On”. On an album that is so clearly influenced by both Dylan and the Byrds, “Drive My Car” and “What Goes On”, enjoyable as they are, sound jarring to the ear, like throwbacks to A Hard Day’s Night.

And yet, these are quibbles. In fact, it feels like a sin to criticize an album this good over such trifles. The American version of Rubber Soul hangs together a little better musically. But it is shorter, misses one Beatles classic and one near-classic, and is the product of record company control, not artistic control.

“Drive My Car” starts the album with a heavy electric guitar lick and riff, underlined by crashing piano notes, and a lyric that sounds like it was tossed off. But the “beep beep mmm beep beep, yeah!” hook is now indelible in Beatle lore, and the song is great fun. At the end of the day, that’s all it is: great fun. There’s nothing wrong with that, but “Drive My Car” could have fit comfortably on With The Beatles. Any indications that the Beatles were growing by leaps and bounds were not present here.

The same could not be said of “Norwegian Wood”. Lennon’s ode to an affair was such a massive leap forward for the band in terms of their songwriting that it still is a marvel. Lyrically it was a straightforward tale of infidelity, but told with Dylan’s sense of wordplay combined with Lennon’s dark humor: Boy meets girl, they go to her house, they drink and talk, he’s certain they’ll end up in bed, she turns the tables on him and goes to bed alone after first laughing at him, he drunkenly curls up in the tub to sleep, in the morning she’s gone and he sets fire to her home. What?! Had there ever been a lyric like this outside of blues murder ballads? And musically the tune was lovely, a strummed and picked acoustic guitar provided the bulk of the accompaniment, but the lead was played on a sitar, the Indian instrument that George was just beginning to learn. Odd, droning notes sound throughout, and then the brief instrumental hook of sharp notes that must have sounded like nothing else on a pop music record in 1965. No drums, but Ringo makes his presence felt with tambourine and maracas. “Norwegian Wood” is lyrically fascinating (written mainly by Lennon, but with help from McCartney), exotic music, and Lennon’s brilliant vocal performance. The musical world shifted on its axis in the barely two minutes it took Lennon to tell his tale. It stands shoulder-to-shoulder with “Like A Rolling Stone”, “My Generation”, and “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” as one of the essential songs of 1965.

“You Won’t See Me” is one of the underrated gems on the album. Had it been released as a single, and almost every song on Rubber Soul was single-worthy, it would have been a huge hit. Macca sings the lead with the confidence of a man who knows he’s writing better and better songs, and the backing vocals from Lennon, and those gorgeous “ooh la la la” harmony vocals are the icing on the cake. McCartney’s piano and Ringo’s percussion are the main instruments, with a simple guitar part played by George, but the triumph of the song lies in the vocals and the melody, a endlessly repeating hook that drives into your brain and stays. As a trivia note: at 3:30, it was the longest Beatles song to date. Macca knew a good thing when he had it.

The vocals that made “You Won’t See Me” so good are even more clear on Lennon’s brilliant self-analysis “Nowhere Man”. Clearly inspired by The Byrds (who were, of course, inspired by the Beatles), the ringing, jangly guitar was played by Lennon (George played the solo using an identical style of guitar), “Nowhere Man” is one of the first Lennon/McCartney originals that was not a love song. The double-tracked lead vocal and the harmonies from Paul and George beat the Byrds at their own game while Ringo lays down a smooth shuffle beat and McCartney plays a busy bass line that practically skips along. Yet despite the bouncing music, the lyric is a harsh examination of a life that Lennon felt was getting away from him. Despite the fame, money, women, intoxicants (the often unmentioned influence on Rubber Soul was marijuana—just check the cover art), Lennon looked at his life and found himself to be a nowhere man, making plans for nobody. The dichotomy between lyric and music, like that of “Help!” earlier that year, makes the song all the more gripping.

While George Harrison was not yet anywhere near as prolific as Lennon or McCartney, the songs he was writing at this point were nearly as good. They also were clearly influenced by his elders in the band. “Think For Yourself” is a driving rock tune that, unlike “Drive My Car”, manages to sound of a piece with the rest of Rubber Soul. While there is guitar on the song, the lead is played by McCartney’s bass. Macca plays a great bass line, and then doubled it using a fuzz tone on his bass. The result is that one of the bass lines sounds like a heavily distorted guitar. It’s a great sound if used tastefully, as McCartney does here. His bass lines were always tasteful. The guy doesn’t get anywhere near the credit he deserves at one of rock music’s greatest bassists. The beauty of the fuzz tone on the bass is that it brings McCartney’s prodigious talents as a bassist to the fore, putting it in a can’t-miss lead position. George sings lead and, for the first time, he sounds like he knows what he’s doing. He’s still not the sublime singer he became a couple of years later, but at least he no longer sounds like a randy scouse git. He’s helped considerably by the way John and Paul come in with harmonies after the first line of each verse. This was George’s best song so far, though only until the record was flipped and “If I Needed Someone” came on. It was also not a love song, indicating George, too, was starting to think beyond the confines of the traditional rock ‘n’ roll subject matter.

Lennon’s “The Word” was about love, but in a decidedly different way. Far from the eros of young love, “The Word” makes the case for agape and philia. It’s an early example of a hippie ethos, perhaps, or the first pass at songs that took a more universal approach to the subject of love, like “All You Need Is Love”. It’s got a nifty upright piano lick that kicks it off and Ringo’s drumming is stellar throughout. The music itself proceeds at a syncopated gallop, unlike anything the Beatles had ever attempted before and the lyric definitely caught the zeitgeist of the hippie era a full year before that movement became widely known. There are a few lyrical hiccups (“in the good and the bad books that I have read”) but it’s so unusual for 1965 that those problems don’t matter.

The problems that plague “Michelle” do matter, however. It’s considered a Beatles classic, but I’m not sure why. Yes, there is a lovely sing along melody, and the Greek feel of the guitar is an extrapolation on what had been done a year before with “And I Love Her”. But ye gods, those lyrics. McCartney brought his amazing ear for melody to the song, but the lyrics are so trite and hackneyed they are cringe-worthy. Yes, the “ooh”-ing backing vocals are beautifully done, but there’s simply no forgiving the lyrics. The fact that many of them are sung in French makes it even worse. “Michelle” is not a bad song. Musically it’s quite good, and the vocal performance is as good as any on the album. It’s simply too bad that McCartney didn’t take ten more minutes to write some better lyrics.

Side two begins somewhat disappointingly. Yes, “What Goes On” is thoroughly enjoyable, but the faux-country music didn’t suit the Beatles any more here than it did on “Act Naturally”. Like that earlier song, this one was given to Ringo as his number. The Beatles could be admired for ensuring that all voices were heard on every album, but it seems clear that the songs given to Ringo were likely the ones that Lennon and/or McCartney thought were substandard.

It’s also clear that Lennon especially was firing on all cylinders at this time. His stunningly gorgeous “Girl” is a near perfect masterpiece of both lyrics and music. That Greek feel once again raises its head, but in a far more convincing way than on “Michelle.” The very simple rhythm provided by Ringo’s percussion and McCartney’s bass give all the support the song needs. Musically the only thing that matters is that beautifully played guitar. The lyrics were worthy of Dylan, with lines that paint a picture of the unnamed girl as a full flesh-and-blood person. The sharp intake of breath that punctuates the single, repeated word of the chorus could make the girl seem breathtaking, or mimic dragging on a joint. The backing vocal, amazingly missed or misunderstood by the critics of the day, features the chant of “tit tit tit.” Yet this is not a drugs or sex song; it’s a meditation on a toxic relationship. “She’s the kind of girl who puts you down when friends are there”, “when I think of all the times I tried so hard to leave her”, “she promises the earth to me and I believe her/after all this time I don’t know why”. And does the singer threaten or promise to kill himself at the end, when all of his efforts to appease this girl have proven fruitless? This is pretty heady stuff from the guy who only two years earlier just wanted to hold your hand.

Immediately on the heels of this comes “I’m Looking Through You”, McCartney’s jaunty take on a similar situation. In this case it’s a relationship that has gone bad. It’s nowhere near the sophistication of “Girl”, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a treasure chest of pop hooks and jangly guitar. It’s easy to picture “I’m Looking Through You” as the musical template for the Monkees. Even as a child I couldn’t hear this song without hearing the similarity to a dozen Monkees songs. It’s a pop music gem that often gets overlooked because it’s sandwiched between two of the greatest Beatles songs ever.

“In My Life” is the flip of “Girl”. Instead of a poisonous romantic relationship, Lennon surveys all the many good relationships that have marked his life. It’s now a wedding favorite, and one of the most covered songs in the Beatles canon. This is Lennon’s “Yesterday” though it’s superior to that McCartney song in almost every way. But it’s not simply Lennon’s song. McCartney claims to have written the music (Lennon claimed McCartney wrote the melody) and their producer George Martin is responsible for the gorgeous, Bach-like piano solo (sped up so that it sounds like a harpsichord). Ringo plays a beautifully sympathetic drum part and George plays the simple lead guitar hook that opens the song and leads into the verses. This was a band effort, marrying some of the best music the Beatles ever did to one of Lennon’s best lyrics. On an album that is stuffed to the breaking point with timeless pop music gems, “In My Life” stands alone at the top. It is one of the most transcendent pop songs of the 20th century.

Of course, anything after that is bound to be a bit of a letdown, but it’s only in comparison to what came before that “Wait” and “If I Needed Someone” suffer in any way. “Wait” was originally recorded for Help! and it’s a mystery why it was bypassed in favor of “Dizzy Miss Lizzy” or “Act Naturally.” Of course, “Wait” was also sweetened for Rubber Soul with several overdubs and vocal harmonies. It’s possible that without this sweetening the song was considered sub-par. But “Wait” remains a lost gem in the Beatles songbook. Ringo rides a tambourine for all it’s worth, and the shared lead vocals between John and Paul are the two singers doing what they do best. Lyrically it’s nothing to write home about. Essentially it’s a lyrical rewrite of “When I Get Home” or “Things We Said Today” but the music fits in as part of the new “folk rock” sound.

This is true in spades for George’s “If I Needed Someone”. The guitar and wordless harmony vocals are heavily inspired by “The Bells Of Rhymney” from the Byrds. But if “Think For Yourself” was George’s best song to that point, it was quickly surpassed here. “If I Needed Someone” is the greatest song the Byrds never did. It’s a wonder they didn’t cover it, probably because they knew they couldn’t improve on it. The lyrics are pretty simple, an ambivalent look at a prospective lover that could be boiled down to an even more simple “You’ll do in a pinch”. George wasn’t writing anything near the quality of Lennon or even McCartney when it came to the words. But the arrangement is glorious, all ringing guitars, Byrds-like vocals, a throbbing bass line underlining it all. It was also George’s best vocal, although he got much help from John and Paul on the verses.

There’s no doubt that Rubber Soul does not end as well as it should. “Run For Your Life”, a song Lennon absolutely hated, is much more of a by-the-numbers song, built around a lyric lifted verbatim from Elvis Presley’s Sun Records classic “Baby Let’s Play House”. The song is nowhere near as bad as Lennon believed, but it’s more a victory of style over substance. This is a top-notch performance of a decent song, and I can see why the guy who had just written “Norwegian Wood”, “Girl”, and “In My Life” might think it was garbage. But it isn’t garbage. It’s just not on the same level as the other songs Lennon was writing at the time.

Rubber Soul is the first masterpiece LP by the Beatles, showing them responding to the gauntlet thrown down by Dylan and the Byrds. This is the album that inspired Brian Wilson to do his greatest work on Pet Sounds. It was the clearest example yet that the Beatles were far more than flash-in-the-pan lovable Moptops, that they could craft a full album’s worth of songs that were as good as or better than the best of their contemporaries. Astonishingly, it was just the beginning.

Grade: A+