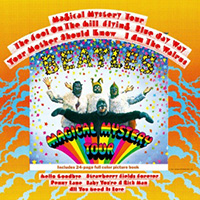

Released less than six months after the glory of Sgt. Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour is not really an album. At least, it wasn’t at the time. It was never released in England until the compact disc era. In truth, it was another money-grabbing effort from Capitol Records to milk a little more cash out of the audience. Ah, but what an effort…

In England, Magical Mystery Tour was released as an EP consisting of six songs on two slabs of vinyl. The songs were the soundtrack to a new movie made by, and starring, the Beatles. Since the EP market didn’t exist in America, Capitol Records took the six songs and added three recent singles, including the pre-Pepper “Strawberry Fields Forever/Penny Lane” single, the post-Pepper “All You Need Is Love/Baby You’re A Rich Man” single, and “Hello Goodbye” the A-side of the current single. But in this case, the desire for more sales accidentally created a masterpiece. There’s really no comparison: the American version of the Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack is so much better than the officially released EP that even the Beatles were forced to acknowledge it by making the American version the official version in 1987.

| U.S. Edition | U.K. Edition |

| 1. Magical Mystery Tour 2. The Fool on the Hill 3. Flying 4. Blue Jay Way 5. Your Mother Should Know 6. I Am The Walrus 7. Hello Goodbye 8. Strawberry Fields Forever 9. Penny Lane 10. Baby You’re A Rich Man 11. All You Need Is Love |

1. Magical Mystery Tour 2. Your Mother Should Know 3. I Am The Walrus 4. The Fool On The Hill 5. Flying 6. Blue Jay Way |

Everything about the American version works better. Even the sequencing of the six soundtrack songs has a far better flow and pace than the double EP version. The packaging of the album, a gatefold with a 24-page booklet featuring a bizarre Beatles cartoon story and a series of extremely odd photographs, also benefits from being the larger LP size. It should be remembered how strange this must have seemed to the American audience. The Magical Mystery Tour movie was made specifically for the BBC and was never shown in America (lucky us), which means that the photographs and cartoon story had no real context outside of the album art. Why is there a photo of John Lennon dressed as a waiter shoveling mounds of spaghetti and what look like rags onto the plate of a large woman? Why is Paul McCartney in a military uniform? Why are there cartoons of the Beatles dressed as wizards? Who the hell is Little Nicola and why is she so adamant that I am not, in fact, the Walrus? Why are the Beatles, if it’s really them, dressed up like animals on the front cover?

The answer, of course, is that it was all part of a trippy mess of a movie, but the Americans didn’t know any of that, aside from a brief mention in the gatefold. What they knew was the music, most of which was sublime.

The title track serves much the same purpose as the title track of Sgt. Pepper. It’s a grand fanfare and an introduction. Separated from the movie, the song still works as an album intro, promising a journey to lands unknown in the songs that follow. It’s a loud, brassy song with simple lyrics that can be read two ways: the literal interpretation of a magical tour, and the metaphorical reading that reveals the drug references. “Magical Mystery Tour” is a drug song, starting with John Lennon’s carnival barker shout of “Roll up for the Magical Mystery Tour!”, a line that uses a common English phrase as code for the act of rolling a joint. The entire concept of the song, written by Paul McCartney, is based on the notion of tripping, taking the common British bus tour and using it as a metaphor for a journey to magical lands. But it is, in the end, still just a fanfare. The lyrics are simple and repetitive, saved from banality by the McCartney’s lead vocal and by the driving, propulsive music. Lyrically it’s even simpler than Sgt. Pepper‘s opening salvo, though the song itself is longer. Removed from its context it’s not a great song, but it’s a world-class album opener. It’s short enough that it doesn’t wear on the listener, punchy enough to force you to pay attention, and catchy enough to leave it stuck in your head. “Magical Mystery Tour” is less a song and more a mission statement. As such, it’s the perfect introduction to the songs that follow.

“The Fool On The Hill” is the first Beatles song to reflect their newfound admiration for the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, a short, bearded guru with a girlish giggle who turned the Beatles on to Transcendental Meditation. At this point, the band was still enthralled with the diminutive Indian and McCartney’s “The Fool On The Hill” is a loving tribute, portraying the Maharishi as a misunderstood wise man while playing with the imagery of the man with the answers to life’s questions being seated at the top of a mountain. It hearkens back to the literary convention, used most famously by William Shakespeare, of having the Fool be the only person who can speak the truth that others don’t want to hear. The powerful brass of the preceding song is here replaced with flutes and woodwind instruments that float throughout the song, lending an airiness and a baroque sense of sophistication to the music that perfectly complements the naïve lyrics.

This is followed by a song that is one-of-a-kind in Beatles history. “Flying” is the only song credited to all four Beatles, and is the only instrumental they ever officially released. In the film, “Flying” is the soundtrack to a collection of unused footage that had been filmed for the trippy “stargate” sequence of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and it’s one of the few parts of the movie that genuinely works well. On record, distanced from the visuals, “Flying” still manages to achieve its desired effect. The title clues the listener in to what to expect, and the music doesn’t disappoint. The music glides and swirls. Keep the title in mind and close your eyes and you will see landscapes below you and clouds ahead. It’s very brief, just a bit over two minutes and the last thirty seconds or so is some Mellotron squealing and backwards tapes that provides a perfect segue into George Harrison’s “Blue Jay Way”.

One of the key elements to Beatles music has always been humor. All four of the them were very, very funny. “Blue Jay Way” sounds mysterious and dark, psychedelic and moody. But the lyrics are actually typical Harrison humor. The song was composed when Harrison was waiting for Derek Taylor to arrive at a house he had rented in Los Angeles. Taylor was late, and had gotten lost. Harrison, at the point of exhaustion, passed the time by playing a Hammond organ and making up lyrics about his friends. The mysterious, atonal, psychedelia of the music is paired with lyrics that could have come from a Monty Python song:

There’s a fog upon L.A.

And my friends have lost their way

They’ll be over soon, they said

Now they’ve lost themselves instead

Please don’t be long

It’s the “they’ve lost themselves” that makes it, a wonderfully eccentric turn of phrase. The music on “Blue Jay Way” is probably the most psychedelic the Beatles ever got, which makes the next song on the album all the more jarring. “Your Mother Should Know” is a McCartney soft-shoe shuffle that harkens back to English music hall. It’s a thoroughly enjoyable trifle, as good as or better than most of McCartney’s similar excursions (“When I’m 64”, “Honey Pie”). It’s the kind of track that would never be approved by a record company today because it doesn’t sound like the other songs on the album, but the Beatles never felt constrained by the need to stick to a formula. They were restless in their creativity and went wherever the song happened to take them. In the case of “Your Mother Should Know” that creativity took them to a time before Elvis shook their worlds, a sound that may have opened the ears of some of their fans.

It was the last song on side one, the final song that appeared in the Magical Mystery Tour movie that really opened ears. John Lennon had heard that there was a course that analyzed Beatles lyrics being offered at his old high school in Liverpool, something he considered absolutely absurd. “I Am The Walrus” was his response, a series of images and lyrics that seemed to make sense in a Jabberwocky kind of way but were, in the end, meaningless. This was Lennon playing with words and having a grand time doing it. The images were sometimes shocking (“pornographic priestess”, “yellow-matter custard dripping from a dead dog’s eye”), sometimes funny (“crabalocker fishwife”, “I am the eggman”), and sometimes coded (“elementary penguins” were Hare Krishnas, “semolina pilchard” was a reference to Norman Pilcher, a British police officer who was notorious for busting rock stars for drugs and even more notorious for bringing his own just to be sure the charges stuck). “Lucy in the sky” gets a shoutout, and the opening couplet came to Lennon on separate acid trips, and it was all punctuated with the refrain “Goo goo g’joob!” The ending includes dialogue taken from a radio production of King Lear and a chanting chorus that repeats the phrase “everybody’s got one” and “oompah oompah stick it up your jumper”. Musically, the song stands with “A Day in the Life” and “Strawberry Fields Forever” as one of the band’s crowning achievements, largely due to producer George Martin’s ability to interpret the desires of his unschooled musicians. There is a rock band of guitar, bass, drums, and piano at the heart of “I Am The Walrus” but it’s the churning orchestration led by violins and cellos, with brass punctuation marks, that make the song stand out. The orchestration adds a veneer of sophistication and respectability. The song seems to be an important statement because the music is so serious. Ironically, a song written to mock the people who took Lennon’s lyrics too seriously sent people into a tizzy as they tried to figure out the meaning of this word jumble. Absent the orchestration, it’s likely that Lennon’s words would have been taken for what they were: a joke. But by adding the hallmarks of so-called “serious” music the Beatles made the joke all that much funnier. “I Am the Walrus” is the greatest musical practical joke ever played.

And it was a B-side of a single. Not even deemed worthy of being the A-side, much to Lennon’s annoyance.

The song that was the A-side of that single led off the second side of the album. “Hello Goodbye” is certainly a better single than “I Am the Walrus” even if it falls far short as a musical innovation. “Hello Goodbye” is insanely catchy, perhaps the catchiest thing Paul McCartney ever wrote (and that’s saying something). One listen and it’s hooked into your brain forever. The simple yin/yang lyrics are easily remembered and the melody is unforgettable. It may not be the achievement that “Walrus” was, but it was unquestionably a more marketable single. “I Am the Walrus” was a brilliantly disorienting slice of surrealism and wordplay. “Hello Goodbye” was a markedly less brilliant solid gold radio-ready hit.

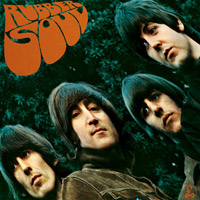

What’s ironic about this is that the two songs that follow “Hello Goodbye” were the two sides of a double A-side single that had been released in February of 1967, months before Sgt. Pepper changed the musical landscape. That single, considered one of the greatest singles ever released, was also the first Beatles single to fail to make the top of the charts. “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” were a huge leap forward when they were released as the first Beatles single after Revolver. Perhaps it was too far a leap, because the single stalled at number two in the charts, held back by Engelbert Humperdinck’s “Release Me”. That doesn’t change that both sides of the single were masterpieces. The songs had been recorded for Sgt. Pepper but rush released as a single when that album was delayed. They became the centerpiece of the second side of Magical Mystery Tour instead, and their inclusion elevates the entire album. There is a slight difference in tone between these songs and the rest of the tracks on the album…they’re not a perfect fit as they would have been on Pepper, but one would have to be a long-faced, humorless scold to care. When an LP is blessed to have both sides of what may be the greatest single in rock history (all votes for “Paperback Writer”/”Rain” will be counted), the idea that the songs sound like they were recorded at a different time and mindset is the lowest form of nitpicking.

If there is a fly in the ointment of the LP it’s “Baby You’re A Rich Man”. Comprised of two songs blended together (Lennon’s “One of the Beautiful People” and McCartney’s “Baby You’re A Rich Man”), the music features a discordant and harsh clavioline, not entirely pleasing to the ear. Lennon’s vocal melody is excellent though the vocal itself isn’t his strongest, and McCartney’s chorus is loud and brash, but both are somewhat undercut by the willfully defiant music. Rolling Stone Brian Jones pops up tooting on an oboe throughout the song, and Mick Jagger is rumored to be a backing voice in the finale. The song was thought to be about Beatles manager Brian Epstein (allegedly Lennon sings “baby you’re a rich fag Jew” at one point, but I’ve never heard it), but Lennon insisted that the song was a message to people to quit whining about their status in life, that we were all “rich”. Unfortunately, the lyrics are something of a mess (“You keep all your money in a big brown bag/Inside a zoo/What a thing to do”, contributed by McCartney, may be one of the dumbest lyrics ever written), so Lennon’s theme never becomes clear.

The lyrics of Magical Mystery Tour‘s final track are also something of a mess. The chorus made the song the anthem of the so-called “Summer of Love” when it was released as a single a month after Sgt. Pepper, but the verses are a circular mash of word soup. How do you parse “There’s nothing you can do that can’t be done” or “Nothing you can sing that can’t be sung”? At first glance, the lyrics seem like a “You can do it!” affirmation but what Lennon is really saying throughout the song is that you can’t do it. If it can’t be done, you can do nothing; if it can’t be sung, you can sing nothing; if it can’t be known, you can know nothing; if it isn’t shown, you can see nothing. This is reinforced by the one exception: “There nothing you can say/But you can learn how to play the game”. The chorus seems like a non-sequitur: “All you need is love/Love is all you need”. Lyrically, “All You Need is Love” takes a somewhat darker and more cynical tone than it is ever given credit for. “Love is all you need,” Lennon sings in the chorus, while the verses hammer home the message “because you don’t/can’t have anything else.” You can learn how to play the game, but if it’s not already being done you can’t do it. “All You Need Is Love” is Lennon’s message to the voiceless, powerless masses that they don’t need the trappings of modern life as long as they have love. It’s a childlike message but, as he did later with the even more naïve “Imagine”, he uses the music to sell the message. “All You Need Is Love” is a beautiful song, from the opening bars of “Le Marseillaise” to the winding close that incorporates musical themes from “Greensleeves” and “In The Mood” and lyrical shoutouts to “Yesterday” and “She Loves You”. The chorus is simple, making it perfect for singalongs and sloganeering (much like the vastly inferior song “Give Peace A Chance”), and the verses are melodic and sung beautifully by Lennon.

Magical Mystery Tour is not an album, but it is a magnificent LP record. Some of the best songs the Beatles ever did grace its grooves and even the songs that don’t rise to that level are excellent. The Beatles canon is improved by its inclusion.

Grade: A+