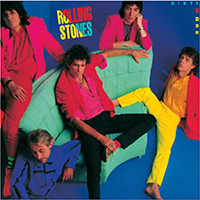

Somewhere out there in this big beautiful world, there is a person whose favorite album of all time, the album that he or she considers the greatest album ever recorded, is Dirty Work.

Somewhere out there in this big beautiful world, there is a person whose favorite album of all time, the album that he or she considers the greatest album ever recorded, is Dirty Work.

That person is not me.

The Stones nearly imploded in the years following Undercover. Mick Jagger announced his intention to launch a solo career, much to the indignation of Keith Richards. The two band leaders feuded openly and bitterly in the press. Jagger’s solo album She’s The Boss, a truly lamentable slice of mid-80s pop rock was released in 1985 and spawned a couple of hits. Later that year Jagger teamed up with David Bowie for a truly embarrassing video for “Dancing In The Streets” which premiered during the Live Aid global broadcast. Jagger himself appeared at Live Aid, singing with Tina Turner. Keith Richards and Ron Wood showed up at Live Aid, as well, backing an almost incoherent Bob Dylan. All of this time, they were dogged with questions about the Stones: what’s next for the band? The reactions from both Mick and Keith were disheartening to any Stones fan. The anger was real between them, and boiling over.

The band managed to drag themselves into the studio in mid-1985 to begin work on Undercover‘s successor, but the bad vibes between Mick and Keith continued. Jagger wasn’t particularly interested in the project, and wanted to spend the time promoting his solo album. This led to several songs being credited to Jagger-Richards-Wood, as Ronnie picked up the slack from Jagger’s disinterest. Credits to the contrary, none of the songs were actual Jagger/Richards collaborations.

The result was an album that was full of inchoate passion. It’s unquestionably the angriest album in the Stones canon, from the opening “One Hit (To The Body)” and “Fight” to “Had It With You” and “Dirty Work”. Dirty Work is certainly the effort of a band that was being riven by animosity.

That could have worked for the band if the songs themselves hadn’t been so lackluster. There’s a feeling you get when listening to the album that the band spent most of the time in the studio thinking, “Let’s get this over with.” The result is a largely unlikeable listening experience.

To be fair, there are a few true gems buried on the album. “One Hit (To The Body)” features some slashing guitar work from guest Jimmy Page. Jagger roars his way through “Fight”. “Dirty Work” and “Had It With You” straddle the line between pissed off and funny. “Sleep Tonight” is a nice Keith ballad that ends the album on a quiet note. There’s a brief coda by Ian Stewart.

And then there’s the rest of the album.

Dirty Work is mercifully short, with only ten songs clocking in at 40 minutes, and as dysfunctional as the band may have been at this point they were at least savvy enough to start strong and finish strong. “One Hit (To The Body)” starts the album in a welter of slashing electric and acoustic guitar chords from Richards and Wood. Charlie Watts plays one of the most uninteresting drum parts of his career while Jagger shouts the lyrics, backed by a chorus of guest stars (including Bobby Womack, Bruce Springsteen’s then backup singer, now wife, Patti Scialfa, and Kirsty MacColl). There’s a sloppy guitar solo played by Jimmy Page, at the time wasting his career with Paul Rodgers in The Firm. The song, along with the one that follows it, is an attack. The experimentation of Undercover is gone here, replaced by an in-your-face production that sounded raw on a first listen but still retains the overly bright sheen that hid the rough edges of rock music in the mid-80s. “One Hit” is good, but not great. It is the hardest rocking Stones song in many years (in some ways, Dirty Work is their hardest rocking effort since Some Girls), but it doesn’t sound like the work of a real band. There’s no real sense of interplay in the music, and Jagger’s “So help me God!” lyric is embarrassing. The anger behind the song was clearly real, but this song also marks the first time the Stones don’t sound like a real group. “One Hit”, like the rest of Dirty Work, is faceless.

If anything, “Fight” takes it up a notch. “Gonna pulp you to a mass of bruises/Is that what you’re looking for?” shouts Jagger. “Got to get into a fight/Gonna put the boot in.” The song rocks relentlessly hard, putting even “One Hit” to shame. Like the earlier song, this one is credited to Jagger/Richards/Wood, meaning that the music was written by the two guitar players and represents their anger at the singer, who reciprocated with his lyrics and abrasive performance. At first listen, it’s thrilling. But then you listen closely. Charlie’s keeping a steady beat as he always did, but he sounds like a metronome. There’s a very good, raw, guitar solo and God knows the chords are hit like anvils, but the only thing the song really convinces you of is that it’s played by angry musicians. The band members were all at odds and, amazingly, the components of the music sound the same way.

Perhaps sensing that they were overdoing it, the third song completely retrenched. It’s a cover of Bob and Earl’s R&B classic “Harlem Shuffle” and, surprisingly, is one of the most cohesive songs on the album. It’s not a great cover. Their versions of R&B chestnuts from “Pain In My Heart” and “That’s How Strong My Love Is” up to “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” and “Just My Imagination” throw the weakness of “Harlem Shuffle” into sharp relief. It’s not helped by Steve Lillywhite’s neon production. The fact that “Harlem Shuffle” was the leadoff single for the album is testament to how both the band and the record company felt about the original songs. This was the first time the Stones had released a studio-recorded cover song as a single since “Ain’t Too Proud To Beg” in 1974, and only the second time they’d done this since 1965, when they were still learning to write originals. Once again Charlie hits a metronomic beat that drags the song down. The beat on these songs is steady, but Charlie Watts is never boring and the drum tracks on these songs is flat and lifeless. What Stones fans didn’t know at the time was that Charlie, long considered the “straight” member of the band, was deep into a nasty heroin addiction at this time (Jagger later said he didn’t want to tour after Dirty Work because he was concerned about how it would affect Charlie). Chalk it up as yet another source of tension within the band and in the record’s grooves.

“Harlem Shuffle” was one of the more musical numbers on the album. It still had that disconnected feel between the instruments, but at least Jagger was singing. On “Hold Back” Jagger is angry, my friends, like an old man sending back soup in a deli. Over a tuneless musical accompaniment, Jagger offers words of wisdom that sound an awful lot like he’s lecturing Keith about his reasons for putting out a solo album. But who knows? You can’t actually understand the lyrics because Jagger shouts them without any regard for melody or rhythm. Jagger bellows like he’s been brushing his teeth with an X-acto knife. “Hold Back” is a full-on assault that will leave the listener cowering in a corner…and not in a good way. By the time its interminable four minutes have ended you feel like you’ve just gotten life advice from some pilled-up lunatic who spends his days screaming about chemtrails and his nights hitting himself in the groin with a plank of wood.

After this sensory overload, the Stones again step back to a cover song. “Too Rude” is the first of Keith’s spotlight moments on the album. Jagger is nowhere to be found. The song is another attempt at reggae from the band, who really hadn’t done a particularly good job at this style since “Luxury” in 1974. “Too Rude” is no exception. Drums with heavy echo can’t disguise another flat beat, and unlike their previous attempts at reggae “Too Rude” sounds nothing like the Stones. It’s clearly a Keith solo song, slapped on the album as filler to close out side one of the record. And yet, despite that, it towers above the two songs that opened the second side of the record.

“Winning Ugly” was the second single, and is almost certainly the worst single the Stones have ever released. Astoundingly, it received an enormous amount of radio exposure in the spring and summer of 1986, reaching number 10 on the rock charts. Once again, Mick’s angry. This time he’s mad at people who will do anything to come out on top. The most obvious targets of the lyrics are the Wall Street fund managers (this was the ’80s, after all) and politicians, though nobody specific is named. Still, a listener could easily think that this is another swipe at Keith with lyrics like

I wanna win that cup and get my money, baby

But, back in the dressing room

the other side is weeping

It’s another largely incoherent rant lyrically speaking but what really kills the song is the production that’s brighter than the pants Jagger’s wearing on the album cover. If “Too Rude” was a solo Keith number, “Winning Ugly” has all the hallmarks of a mid-80s Jagger solo song: the heavy use of female backup singers, the shiny keyboard sound, the prominent disco funk bass (by John Regan, not Bill Wyman). Ever-so-slightly better is “Back To Zero”, another in an endless parade of 80s pop and rock songs about impending nuclear annihilation. Credited to Jagger, Richards and Chuck Leavell, it’s another faux funk track that simply screams “solo Mick”. Listening to it, it’s nearly impossible to imagine that the Rolling Stones are playing on the track (in fact, the guitar is being played by Bobby Womack). Once again Charlie Watts sounds like he was propped up behind the drums with an elaborate pulley system to raise and lower his hands as he held the drumsticks. Dirty Work is like the musical equivalent of Weekend At Bernie’s, with Charlie taking the place of the movie’s titular character.

But all is not lost. Dirty Work concludes with the three best songs on the album. The title track is another broadside at an unnamed person that could easily be about Keith’s abdication of responsibility during his heroin addiction and his Jagger’s subsequent unwillingness to turn the reins of power back over to his band mate. But damn if “Dirty Work” doesn’t swing like a prime slice of vintage Stones. Even Charlie sounds like he’s been roused from his torpor, though most of the swing comes from the guitars. Jagger’s vocals are again shouty and harsh. By this time almost all evidence of the guy who once sang, really sang, ballads like “Wild Horses” or “Love In Vain” is gone in a storm of affectations. But “Dirty Work”, unlike the songs the precede it, has a sense of humor: “You let somebody do the dirty work/Find some loser, find some jerk/Find some greaseball.” The song sounds like the band is once again an actual unit. The tension between Jagger’s vocals and Keith and Ronnie’s guitar is palpable, more than in “One Hit” or “Fight” certainly.

This sudden and dramatic increase in quality gets even steeper with the next cut. “Had It With You” got a bit of radio play in the week leading up to the album’s release because it was the far superior flipside of “Harlem Shuffle”. Then the album came out, with a lyric sheet, and “Had It With You” would never be played on commercial radio again. “I love you dirty fucker/Sister and a brother/Moaning in the moonlight” sings Jagger over a Chuck Berry-style guitar riff. Lyrically it’s the culmination of the entire album. All of the anger that was fuelling Jagger and Richards erupts here: “Loved you in the lean years/Loved you in the fat ones/You’re a mean mistreater/You’re a dirty, dirty rat scum/I’ve had it with you.” Yet, oddly, there’s almost joy in the music. It’s the sound of the Stones playing to all their strengths and sounding, ironically, like they’re having fun. Even Jagger delivers the closest thing to a traditional Mick vocal on the track. His voice is still raspy and filled with odd growls, as if he was chewing sandpaper, but at least he’s not shouting like someone hit his toes with a hammer, like he is on the rest of the album.

The last song on the album is “Sleep Tonight”, a lovely Keith Richards piano ballad that is a bit too long, but still endures. Keith’s been rewriting this song ever since, but never as well as he did here. The production hurts the song as it does the entire album. The drums are too loud and clean (played by Ron Wood, who shows more verve here than Charlie Watts has shown through the rest of the album), and the backing vocals are too prominent. However, it’s a fine ballad that would have fit perfectly on Keith’s later solo album Talk Is Cheap. The song is followed by a raw, bluesy boogie-woogie piano for 30 seconds, a brief excerpt from “Key To The Highway”. Sadly, it’s easy to imagine this being the only thing on the album on which the band could all agree: a brief tribute to Ian Stewart, the straight arrow blues master and sixth Stone who had kept them in line for over 20 years before dying of a heart attack in December of 1985. Dirty Work is dedicated to Stewart, and his piano coda is a genuinely touching moment on an album not known for sentimentality.

Dirty Work was not an interesting experiment gone awry, like Their Satanic Majesties Request. It wasn’t a freeform guitarist audition like Black and Blue. It wasn’t a disinterested filler album like Emotional Rescue. Dirty Work was a bitter, invective-filled divorce-in-progress that left an acid taste in people’s mouths, including the band themselves. It was easy to dismiss Majesties, Black and Blue, or Rescue as anomalies in the band’s storied career. It was much harder to dismiss this album because for the first time it seemed that the Stones were trying really hard to be the Stones, but that they didn’t know what that meant any more. Dirty Work is the album where they lost their identity and ended up sounding almost like a parody of themselves. Afterwards, Jagger went right back to work on his second solo album, and Keith eventually followed that route with far better results. For all practical purposes, the band split up. When asked about the band, they took turns ripping each other and shrugging off the possibility of a future. But the band did have a future, although it would be markedly different from the past it had shared. This was a good thing because it meant that the nadir of their recording career would not be their last gasp.

Grade: D+