Looking for something to read? Here’s the list of my adventures in reading for 2025. For whatever reason I leaned heavily into thrillers, including crime novels, mysteries, and supernatural chillers this year with some non-fiction, and one classic play, thrown into the mix.

The Small Faces & Other Stories – Uli Twelker & Roland Schmitt

This exhaustive chronicle traces English Mod band the Small Faces from their origins through various offshoots and solo ventures, including the Faces, Humble Pie, and Peter Frampton. It’s dry as dust and packed with more detail than even obsessive fans (guilty!) could possibly need. Die-hards might persevere, but most readers will tap out early. Too much story for too concise a book.

Anymore for Anymore: The Ronnie Lane Story – Caroline & David Stafford

Ronnie Lane, the soulful engine behind the Small Faces and Faces, gets a heartfelt portrait here, chronicling his music, his battles, and his enduring spirit. Absorbing and touching, it’s a fitting tribute to one of rock’s undersung heroes. Essential for anyone who loves that loose, boozy Faces magic.

Drums & Demons: The Tragic Journey of Jim Gordon – Joel Selvin

Jim Gordon was one of rock’s most brilliant drummers, laying down classic beats for everyone from Derek and the Dominos to Steely Dan. This heartbreaking biography traces his genius alongside his tragic descent into schizophrenia and murder. Fascinating and utterly devastating—a cautionary tale of unchecked mental illness in the music world.

Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood – Eric Burdon & Jeff Marshall Craig

The gravel-voiced frontman of the Animals recounts his wild ride through the British Invasion, psychedelia, and beyond with no holds barred. Engaging, raw, and full of rock ‘n’ roll anecdotes, it captures Burdon’s fierce personality perfectly, though he sometimes comes across as rock music’s own Zelig or Forrest Gump. A lively memoir from one of the era’s great survivors.

Hot Wired Guitar: The Life of Jeff Beck – Martin Power

Jeff Beck, the elusive Yardbirds guitarist, heavy metal inventor, and fusion pioneer, gets a thorough, guitar-centric biography here. Detailed and admiring, it dives deep into his innovative playing and restless career. Pure heaven for axe enthusiasts. Full review here.

The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Authorized Biography – Charles White

This authorized biography captures the wild, flamboyant ride of one of rock ‘n’ roll’s true architects and original wild men. Excellent and unfiltered, it celebrates Little Richard’s explosive energy and lasting influence. Essential reading for anyone who loves the roots of rock.

Alice in Chains: The Untold Story – David de Sola

The definitive, exhaustive history of Seattle’s darkest grunge giants traces their rise, demons, and tragic losses in unflinching detail. Dark, thorough, and compelling—it’s the full story behind one of alt-rock’s Big Four.

Pandora’s Box: How Guts, Guile, and Greed Upended TV – Peter Biskind

Biskind follows up Easy Riders, Raging Bulls with a chaotic saga of cable TV’s rise and the streaming revolution that upended everything. Still fascinating, though not quite as electric as his Hollywood classic. A solid dive into how these one-time fledgling upstarts reshaped entertainment.

Little Heaven – Nick Cutter

Mercenaries hired to investigate a religious cult stumble into forest monsters and bloody mayhem in this sprawling horror tale. It’s okay—gory and ambitious—but drags with its length and never quite hits the heights of Cutter’s best.

Those Across the River – Christopher Buehlman

In Depression-era Georgia, a failed academic couple moves to a small town with a dark secret involving werewolves and forgotten rituals. Well-crafted Southern Gothic that masterfully builds dread around the cost of appeasing ancient evils. Elegant and chilling.

Hollywood: The Oral History – Jeanine Basinger & Sam Wasson

This massive compilation of insider voices offers a sometimes fascinating, sometimes maddening peek behind Tinseltown’s curtain. Enlightening and infuriating in equal measure—an excellent read for anyone obsessed with the dream factory’s golden age. Full review here.

An Honest Man – Michael Koryta

On a remote Maine island, murder, drugs, and sex trafficking collide with buried secrets in this taut thriller. Very good, with Koryta’s trademark atmosphere and moral complexity shining through.

The Book of Accidents – Chuck Wendig

A fractured family confronts curses, multiverse horrors, and apocalyptic threats in this ambitious genre mashup. Part horror, part sci-fi—dark, sprawling, and unflinching.

Tell No One – Harlan Coben

A grieving doctor receives messages suggesting his murdered wife is alive, plunging him into a twisty conspiracy. Breakneck pacing and relentless surprises make it a very fast, addictive read.

The Night Parade – Ronald Malfi

A father and young daughter flee across a plague-ravaged America, dodging infected hordes and human threats. Strong, quietly devastating apocalyptic horror that hits hard emotionally.

Moguls: The Lives and Times of Hollywood Film Pioneers Nicholas and Joseph Schenck – Michael Benson & Craig Singer

The Schenck brothers rise from nickelodeons to building the studio system in this interesting history of early Hollywood power players. Solid and informative for film buffs.

Road of Bones – Christopher Golden

On Stalin’s frozen Kolyma Highway, forest spirits and ancient horrors stalk modern travelers. Genuinely chilling Siberian nightmare fuel.

Runnin’ with the Devil: A Backstage Pass to the Wild Times, Loud Rock, and the Down and Dirty Truth Behind the Making of Van Halen – Noel Monk & Joe Layden

Van Halen’s longtime manager spills juicy gossip on America’s premier party band’s wild early years. Fun, decadent, and a total blast.

Fire In The Hole: Stories – Elmore Leonard

This lean collection of sharp tales includes the title story that introduced the world to Raylan Givens. Typically excellent—vintage Leonard gold.

All Hallows – Christopher Golden

A nostalgic 1980s Halloween turns deadly when small-town secrets and childhood fears manifest. Sinister and atmospheric.

Devolution: A Firsthand Account of the Rainier Sasquatch Massacre – Max Brooks

“Found-footage” account of a tech-utopian community facing a Sasquatch massacre after Mount Rainier erupts. The author of the extraordinary World War Z doesn’t rise to that level here, but it’s a fun and scary read.

Goblin – Josh Malerman

Five interconnected novellas unleash creeping dread on a cursed town that despises outsiders. Malerman. the author of Bird Box, delivers atmospheric horror.

A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs, Vol. 1: From Savoy Stompers to Clock Rockers – Andrew Hickey

The print companion to the excellent podcast dives deep into rock’s roots, from swing to early rockers. Fascinating and delightful for music nerds like me. Hickey has figured out how to do a comprehensive history of the music, not through bands and movements, but through songs that pushed the music forward.

Our Lady of Darkness – Fritz Leiber

1970s San Francisco occult paranoia blends ghosts, madness, and ambiguous urban horror. Moody and intellectually frustrating in the best way.

The Lesser Dead – Christopher Buehlman

1970s New York subway vampires face off against feral, hungry vampire children. Creepy, funny, and one of the strongest modern vampire tales. A cousin to John Skipp and Craig Spector’s similarly set The Light At The End.

Homeward Bound: The Life of Paul Simon – Peter Ames Carlin

A thorough, admiring chronicle of the brilliant songwriter’s life and career. Lovingly detailed and insightful. It’s easy to forget now just how massively popular Simon was once upon a time, and Carlin’s tome is a nice reminder that the musician was once a superstar. Full review here.

The Talisman – Stephen King & Peter Straub

Two horror masters craft a magnificent fantasy echoing Huckleberry Finn across parallel worlds. A sprawling, heartfelt, and still dazzling epic quest story.

The Nineties – Chuck Klosterman

A sharp, engaging tour through the decade’s culture, from grunge to 9/11, with extra snark. Fun and nostalgic.

Gwendy’s Magic Feather – Richard Chizmar

The middle entry in the Button Box trilogy suffers from a glaring lack of real plot momentum. Easily the weakest link of the series.

Gwendy’s Final Task – Stephen King & Richard Chizmar

The Button Box trilogy concludes satisfyingly, weaving in Dark Tower connections. A strong finale that is perhaps better than what the series deserves.

American Assassin – Vince Flynn

CIA super-agent Mitch Rapp embarks on his explosive first mission. Adrenaline-fueled action candy.

Just Kids – Patti Smith

Smith’s lyrical memoir recounts her artistic coming-of-age and profound friendship with artist Robert Mapplethorpe in 1970s New York. Engaging, heartfelt, and beautifully written.

Forest Ghost – Graham Masterton

An ecological horror starts promisingly but crumbles under weak characters and a catastrophically dumb ending.

It’s Alive! – Julian David Stone

This roman à clef explores the behind-the-scenes fight to greenlight the 1931 classic Universal film Frankenstein. Mildly interesting but ultimately kind of pointless.

Slow Horses – Mick Herron

The witty, slow-burn debut introduces Slough House’s misfit spies and served as the inspiration for the brilliant Apple TV+ series. A slow start but excellent once it hits its stride.

Haunted – Chuck Palahniuk

Twenty-three macabre tales framed by a gimmicky writers’ retreat novel. Gross, divisive, and ultimately middling.

Twelfth Night – William Shakespeare

The Bard’s funniest comedy sparkles with mistaken identities and farce that feels like the Marx Brothers with poetry. Brilliant and timeless.

Twenty Thousand Roads: The Ballad of Gram Parsons and His Cosmic American Music – David Meyer

This rich biography of Gram Parsons shines, but the opening third of the book drowns in unnecessary detail about the Parsons family business dealings and young Gram’s school years. Still essential for Americana music or country fans. The final two-thirds more than compensate for the slow beginning. Full review here.

The Manitou – Graham Masterton

A ridiculous 1970s premise—ancient Native spirit reborn via tumor—delivers pure schlocky pulp horror. Silly, clichéd, but charmingly fun.

Open Season – C.J. Box

Wyoming game warden Joe Pickett’s debut mystery starts slow but quickly roars into gripping territory. Worth sticking with.

Fever House – Keith Rosson

A severed hand unleashes apocalyptic mayhem and weird violence. Excellent and unhinged.

I Will Find You – Harlan Coben

An innocent father serving a life sentence for murdering his young son receives photographic evidence that the boy may still be alive, prompting him to escape prison and embark on a desperate quest to uncover the truth. Another reliable Coben page-turner packed with twists. Propulsive comfort food.

The Lincoln Lawyer – Michael Connelly

Slick courtroom thriller introducing Mickey Haller, the defense attorney who works out of the back seat of his Lincoln Town Car. Instantly addictive. Haller’s a great character and Connelly is a fine writer.

Departure 37 – Scott Carson

Hundreds of pilots across America receive eerie midnight calls from their mothers—some deceased—begging them not to fly, causing a nationwide grounding of flights, and a teenage girl uncovers ties to a buried Cold War secret involving a scientist’s dangerous experiment. Thriller blends sci-fi and coming-of-age elements, tying up neatly. Ambitious but not Carson’s strongest.

A Drink Before the War – Dennis Lehane

Boston noir explodes with the compulsive debut of investigators Patrick Kenzie and Angela Gennaro, who are hired to track down a cleaning woman who allegedly stole confidential documents, only to uncover evidence of political corruption and street gang rivalries that ignite a brutal racial gang war in their city. Excellent from the jump.

Deal Breaker – Harlan Coben

Sports agent Myron Bolitar, on the verge of securing a massive contract for his promising young quarterback client, begins investigating after the athlete receives disturbing evidence suggesting that his former girlfriend—presumed murdered—might still be alive. Snappy, fun comfort read.

Skeleton Crew – Stephen King

King’s strongest short fiction collection delivers chills galore (skip the two poems).

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young – David Browne

Superb biography navigating four massive egos and their harmonious magic. Juicy and insightful.

The Last Kingdom – Bernard Cornwell

Uhtred (son of Uhtred) of Bebbanburg fights amid Saxons and Danes in the brutal founding of England. Epic and the source for the excellent Netflix series.

Darkness, Take My Hand – Dennis Lehane

Private investigartors Kenzie and Gennaro hunt a vicious serial killer. Tense, dark, and utterly gripping.

The Pale Horseman – Bernard Cornwell

Book two of the Saxon stories (the saga of Uhtred of Bebbanburg) ramps up the shield-wall battles and strong characters. In 9th-century England, as Danish invaders threaten to overrun the last Saxon kingdom of Wessex, the pagan warrior Uhtred of Bebbanburg—torn between his Viking upbringing and his oath to the pious King Alfred—flees into hiding after a devastating defeat, rallies forces from the marshes, and leads a daring campaign to turn the tide against the Viking hordes. Cornwell at his historical best.

The Secret Hours – Mick Herron

A seemingly futile government inquiry called Monochrome, tasked with investigating historical misconduct in the British intelligence service but stonewalled at every turn, is reignited when a classified dossier surfaces detailing a botched 1994 operation in post-Cold War Berlin. Time-hopping spy tale uncovers Slough House’s origins and provides the back story for Jackson Lamb. Essential for Slow Horses fans.

American Psycho – Bret Easton Ellis

Ultra-violent satire skewers Wall Street excess and emptiness. Savage and thought-provoking. I still can’t decide whether it’s over-the-top violence porn or brilliant satire. Maybe both.

Seeing the Light: Inside the Velvet Underground – Rob Jovanovic

Surface-level bio of Warhol’s house band offers interest but never digs deep enough.

Wild Town – Jim Thompson

In a corrupt West Texas oil boomtown an ex-con gets a job as hotel detective for a wealthy wildcatter, only to owe a favor to the deceptively folksy deputy sheriff and become entangled in seduction and betrayal involving the oilman’s alluring young wife. Flat, forgettable noir that ranks as one of Thompson’s rare misses.

Sacred – Dennis Lehane

Boston private investigators Patrick Kenzie and Angela Gennaro are recruited by a terminally ill billionaire to locate his missing daughter and the private detective who vanished while searching for her. Book three for Kenzie and Gennaro delivers brutal, modern noir.

The Hollow Kind – Andy Davidson

In 1989, Nellie Gardner escapes an abusive marriage by moving with her son to the inherited Georgia estate of her estranged grandfather, only to confront an ancient, shape-shifting supernatural evil rooted in the land and intertwined with her family’s multi-generational history of greed, sacrifice, and horror dating back to 1917. Well-crafted dual timeline Southern Gothic horror that somehow failed to hold my attention despite checking all the boxes.

The Black Echo – Michael Connelly

LAPD homicide detective Harry Bosch investigates the apparent overdose death of a fellow soldier from his unit. Outstanding debut of the stubborn, jazz-loving detective Bosch. Instantly addictive police procedural.

Who Goes There? – John W. Campbell

The 1938 Antarctic isolation nightmare that inspired The Thing. Pure claustrophobic dread.

The Pretty Ones – Ania Ahlborn

Set against the backdrop of NYC’s 1977 “Summer of Sam”, a lonely office worker finally gets some of the attention she desperately seeks, with murderous results. Strong writing and characters undone by total predictability.

Marathon Man – William Goldman

In 1970s New York City, a grad student and marathon runner becomes wrapped up in a deadly conspiracy when his older brother is mortally wounded and dies in his arms, drawing him into a terrifying confrontation with a notorious Nazi war criminal emerging from hiding to retrieve a fortune in diamonds. Paranoia thriller immortalizing the question “Is it safe?” Masterful tension and villainy.

Orphan X – Gregg Hurwitz

Government-trained assassin helps the desperate in this morally gray, jet-fueled thriller. Similar to Lee Child’s Reacher series, but better.

After Dark, My Sweet – Jim Thompson

Unstable ex-boxer drifts into a kidnapping scheme with an added fatal attraction. Classic Thompson noir that still packs a punch.

I Call Upon Thee – Ania Ahlborn

A woman returns home after tragedy, confronting childhood supernatural horrors she fled. Very good, atmospheric dread. Don’t play with Ouija boards.

No Second Chance – Harlan Coben

Doctor’s daughter kidnapped after wife’s murder in this relentless kidnapping and child trafficking thriller. One of Coben’s strongest.

The Prophet – Michael Koryta

Estranged brothers haunted by past tragedy face new murders amid high school football glory. Mostly excellent, though football details occasionally overwhelm.

Magic – William Goldman

Ventriloquist/magician descends into madness with his sinister dummy. Very good psychological chiller that powered the creepy Hopkins film.

The Brass Verdict – Michael Connelly

Defense attorney Mickey Haller inherits a murdered lawyer’s caseload, including a high-profile murder trial, and crosses paths with Detective Harry Bosch. Connelly masterfully unites his two iconic characters in a tense, twisty legal thriller. Haller and Bosch’s wary alliance elevates the stakes brilliantly.

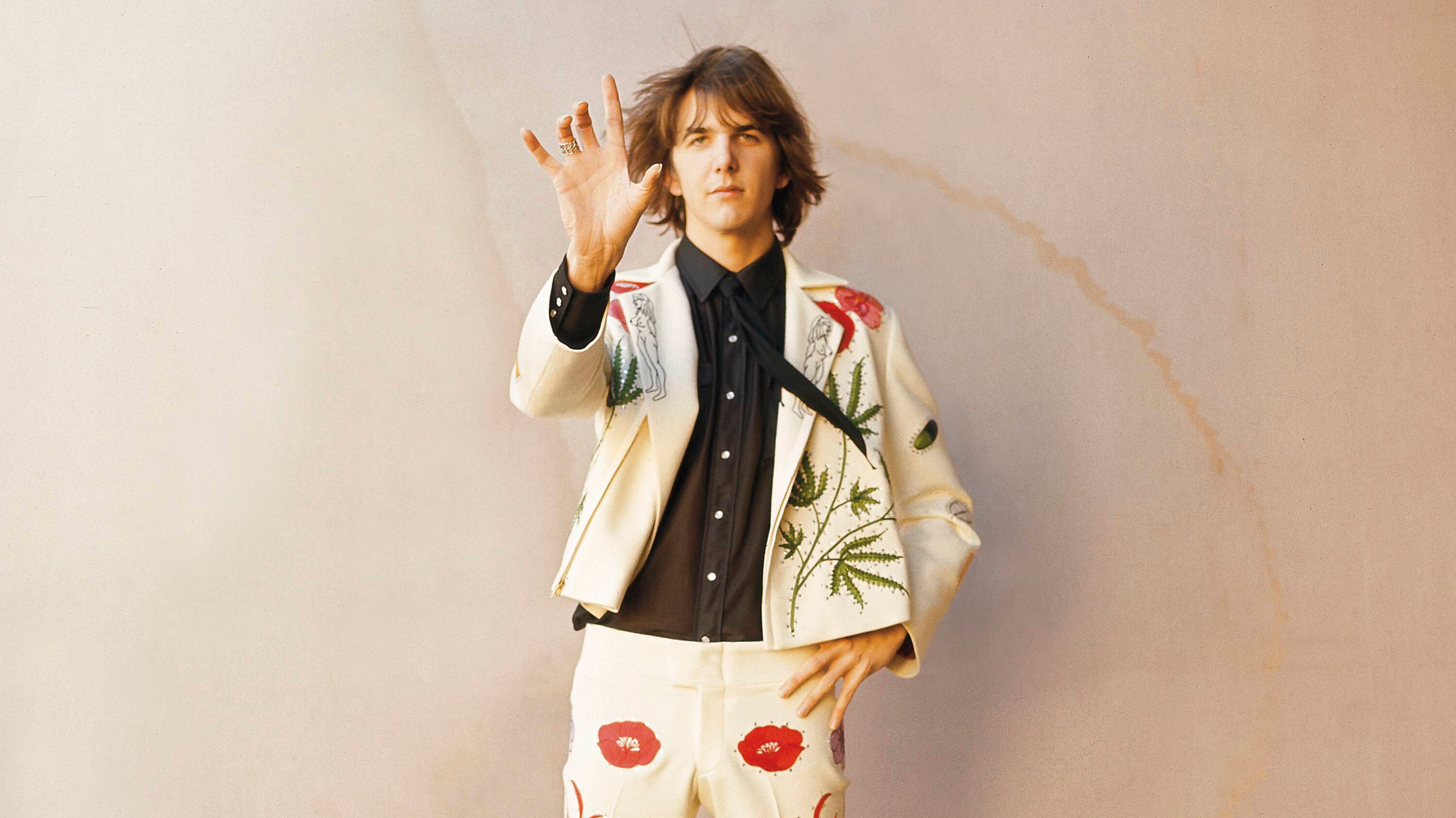

In 2008 a brash rocker came out of San Francisco with his first, self-titled, album. Ty Segall was a brief, noisy album of distinctly lo-fi rock. Under the murk and the distortion was a Nuggets-style garage rock album (at 23 minutes closer to an EP). Since then Segall has been releasing albums on his own and with various side projects at a pace that even Ryan Adams and Guided By Voices can’t hope to match. By my count, he’s put out 28 albums in the past 18 years. Of course, anyone who is that prolific is someone who by definition does not have an editor, and Segall has released some real junk over the course of his career. Some of his albums border on noise, and not a pleasant noise. But Segall is also capable of writing some incredible songs, and several of his albums are truly excellent. Such is the story of a restless, inventive musician who clearly burns with the desire to create. A new Ty Segall album is always worth checking out because you never know what to expect, and when he’s good he’s exceptional.

In 2008 a brash rocker came out of San Francisco with his first, self-titled, album. Ty Segall was a brief, noisy album of distinctly lo-fi rock. Under the murk and the distortion was a Nuggets-style garage rock album (at 23 minutes closer to an EP). Since then Segall has been releasing albums on his own and with various side projects at a pace that even Ryan Adams and Guided By Voices can’t hope to match. By my count, he’s put out 28 albums in the past 18 years. Of course, anyone who is that prolific is someone who by definition does not have an editor, and Segall has released some real junk over the course of his career. Some of his albums border on noise, and not a pleasant noise. But Segall is also capable of writing some incredible songs, and several of his albums are truly excellent. Such is the story of a restless, inventive musician who clearly burns with the desire to create. A new Ty Segall album is always worth checking out because you never know what to expect, and when he’s good he’s exceptional.

Americana came out of the dusty crossroads of folk, country, blues, rock, and soul. In its earliest iterations as “roots rock” it came in the shape of The Band, Gram Parsons, The Blasters, and others. It was always a responsive type of music. The Band were responding to the excesses of Sgt. Pepper and Cream. Parsons was responding to what he believed was the soulless aspect of modern country music. The Blasters were a breath of fresh air amidst the rhinestones and huge hair of the late seventies and early eighties, as well as a riposte to the punk ethos of burning down the past and starting anew. The Blasters wallowed in older styles of music and called their first album American Music. Throughout the eighties, nobody quite knew what to call this style of music that was neither fish nor fowl. Eventually the term “alt-country” was used to describe bands like The Jayhawks and Uncle Tupelo, and then that label gave way to “No Depression,” named after the Carter Family song covered by Uncle Tupelo. Desperate for a label that would stick, the Grammy Awards instituted “Americana” as a category in 1990. It was, and still is, something of a catch-all.

Americana came out of the dusty crossroads of folk, country, blues, rock, and soul. In its earliest iterations as “roots rock” it came in the shape of The Band, Gram Parsons, The Blasters, and others. It was always a responsive type of music. The Band were responding to the excesses of Sgt. Pepper and Cream. Parsons was responding to what he believed was the soulless aspect of modern country music. The Blasters were a breath of fresh air amidst the rhinestones and huge hair of the late seventies and early eighties, as well as a riposte to the punk ethos of burning down the past and starting anew. The Blasters wallowed in older styles of music and called their first album American Music. Throughout the eighties, nobody quite knew what to call this style of music that was neither fish nor fowl. Eventually the term “alt-country” was used to describe bands like The Jayhawks and Uncle Tupelo, and then that label gave way to “No Depression,” named after the Carter Family song covered by Uncle Tupelo. Desperate for a label that would stick, the Grammy Awards instituted “Americana” as a category in 1990. It was, and still is, something of a catch-all. Garage rock came out of the 1960s, a form of raw, back-to-basics rock and roll. The gateway drug for garage rock is the legendary collection Nuggets, originally compiled by future Patti Smith guitarist Lenny Kaye and released in 1972 as a two-record compilation of great lost tracks from the sixties. It has since been expanded into no fewer than five four-disc box sets, focusing on America, international, modern, Los Angeles and San Francisco. They represent an alternative view of the history of rock and roll, one where the big bands of the era are only heard through their influence. And it’s possible to hear all those influences in the three minutes it takes to spin out one of these songs. Part of the fun of garage rock is how it teases the ear, reminding you of something else but remaining fresh.

Garage rock came out of the 1960s, a form of raw, back-to-basics rock and roll. The gateway drug for garage rock is the legendary collection Nuggets, originally compiled by future Patti Smith guitarist Lenny Kaye and released in 1972 as a two-record compilation of great lost tracks from the sixties. It has since been expanded into no fewer than five four-disc box sets, focusing on America, international, modern, Los Angeles and San Francisco. They represent an alternative view of the history of rock and roll, one where the big bands of the era are only heard through their influence. And it’s possible to hear all those influences in the three minutes it takes to spin out one of these songs. Part of the fun of garage rock is how it teases the ear, reminding you of something else but remaining fresh.