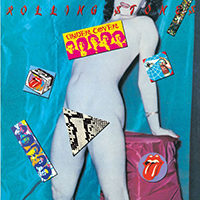

In 1983, the Rolling Stones released yet another album that polarized fans. Undercover was their last blending of dance music and rock, and it was buried in “contemporary” production techniques that sound almost impossibly dated today. The music of the 1980s was blighted by these production standards: drums that sounded like machines (even when they weren’t), a clean, bright sound that smoothed over any and all rough edges, an over-reliance on synthesizers and sound effects, a shrill keyboard sound. Much of the music on Undercover, and even the album cover, was garish and brightly lit: like the decade itself. It’s hard to describe a sound of production techniques but the sound of the 1980s is all right there on side one, track one of Undercover.

“Undercover of the Night” is an almost perfect example of a song from the 1980s: the lyrics are about revolution in Central America, it was a rock song that had a dance groove, the drums sound like they were played on a computer, the bass is very prominent, the guitars slash but don’t really sound like guitars until the terrific solo, there is a wash of synthesizers over everything. But “Undercover” works, as so many other songs from this era failed to do. The production techniques of the time wrapped songs in a gauzy haze. The sound was pristine, but indistinct at the same time. There was no hint of musical interplay. For too many songs, there was no sense of real musicians playing instruments. Everything sounded processed by machines. Many great songs from this era are still difficult to listen to because they sound so bad. The quality of the writing, playing, and singing needed to be extraordinarily good to rise above the production values. Some albums succeeded despite their production (e.g., XTC’s Skylarking is a perfect example of an album where the songs were so good they rose above the neon shininess of the production), but most mainstream albums were suffocated before they had a chance to breathe.

“Undercover of the Night” is an exception. Perhaps it’s because the Stones embraced the new production values that they sound refreshed throughout most of the album. They were no longer even attempting to sound like the band that recorded Exile on Main Street. Instead, they sounded like the most vicious New Wave band on the planet. They brought their trademark aggression and encased it in a sound better suited for Duran Duran or Spandau Ballet. The final results were admittedly spotty, but that had more to do with the material than the production. “Undercover of the Night” is a great song, full of tension and violence. The video, featuring Keith Richards as a skull-masked assassin looking to kill Mick Jagger’s stuffed shirt diplomat, solidifies the impact. Taking a cue from dance music, Bill Wyman’s thick, rubbery bass is the lead instrument, swapping lines with the guitar over Charlie’s mechanized, effects-enhanced drums. Over the backing Jagger barks his lyrics about Communist insurgency in Central America, wisely avoiding choosing sides (there were no good guys in those conflicts). This being the Stones, Jagger makes even revolution sexual as he sings about the prostitutes “done up in lace, done up in rubber” servicing “jerky little GI Joes/On R&R from Cuba and Russia”. It’s a kitchen sink production, with the backwards loops, dub-influenced echo, and phased drums, but still leaves space for a ferocious guitar solo from Ron Wood. “Undercover of the Night” was the first single released from the album and was shocking in a way that the Stones hadn’t achieved since “Miss You”, and for the same reason. The song was the Stones wading into the production values of New Wave and dance music, and emerging with a tough rocker that you could dance to, and a video violent enough to be banned from MTV until it was edited. You can change the sound, but the Stones were still the Stones.

This was proven by “She Was Hot”, a comic sex-romp about groupies who are so steamy they leave even Mick Jagger burnt out. The effects of the previous song are gone here, leaving the band to sound natural again. Charlie Watts and Keith Richards benefit the most from this. Charlie lays down a steady beat and Keith plays a distorted, thick solo. Jagger shouts the funny lyrics, a vocal style that he would use more often as he got older. Undercover has a lot of great singing from Jagger, but also marks the point where his voice started to change into what you hear today: over-enunciated, shouting. The man who sang “Wild Horses” is still there, but time and life were conspiring to change the timbre of his voice.

This vocal style is even more pronounced on “Tie You Up (The Pain of Love)”, Jagger’s nod-and-a-wink song about S&M. In a way it’s a companion piece to “She Was Hot”, just another experience pulled from Jagger’s bottomless well of libertine decadence, but you never get the feeling that Jagger actually means it. When it came to sex, the Stones were always a little cartoonish, and this song fits right in to the milieu. Indeed, Keith has said that the song was something of a joke meant to annoy “mouthy little feminists” who had given the band a difficult time over their perceived misogyny since the days of “Under My Thumb”. Bill Wyman is again the real star of the song, which is a straight rocker with one foot in dance rhythms. There’s also a completely unnecessary conga break that adds nothing but a distraction.

Those dance rhythms are gone in “Wanna Hold You”, another winner in Keith’s string of rockers that dated back to Some Girls‘s “Before They Make Me Run”. From a technical perspective, “Wanna Hold You” is a mess. The backing vocals are all over the place, the lyrics are a throwaway, and Keith slurs the lead vocal. But Charlie Watts once again rides the beat like the old pro he is, and Ron Wood plays a solid bass line. It’s sloppy, but effective, a throwback to a time when the band was more concerned with the feeling of a song and not the perfection of a recording. Four songs in, and Undercover is firing on almost all cylinders. It won’t make anyone forget Sticky Fingers, but it’s clearly their best album since Some Girls.

All of which makes “Feel On Baby” even more disappointing. To call it a half-hearted stab at reggae would be overestimating it. Musically it’s a dull, phony dub/reggae tune mired in awful production values, electronic drums, shrill harmonica, and a go-through-the-motions lyric about hooking up with a girl while on the road. It’s one of the worst songs in the Stones canon.

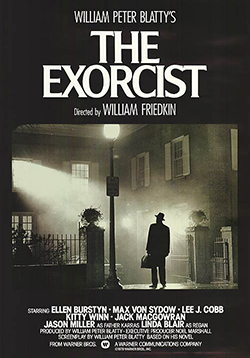

The nadir of “Feel On Baby” is all the more unfortunate because it’s the one song on the album that’s truly bad. “Tie You Up” isn’t great, but otherwise Undercover is a strong album, more interesting and inspired than the overly praised Tattoo You. The second half picks up with “Too Much Blood”, another love-it-or-hate-it song that comes from the dance world. Once again the drums are processed beyond recognition, leaving the listener baffled as to why the Stones would put the great Charlie Watts in an electronic box. The guitars are barely noticeable, but offer a constant plucking and picking that drives the song. Once again, it’s Bill Wyman’s show, though he’s assisted by a punchy horn part. Over it all is a superficial lyric about just wanting to dance in a world that’s gone crazy. What makes the song different, however, is Jagger’s two extended raps. The first is a straight telling of a true murder story from Paris, about a Japanese man who murdered and ate his girlfriend. The second is, to me at least, an hilarious rap about the then-current trend of slasher movies. “You ever see the Texas Chainsaw Massacre? ‘Orrible, wasn’t it?” Jagger asks. “Oh no, don’t saw off me leg…don’t saw off me arm…When I go to the movies I like to see something more romantic. You know, like Officer and A Gentleman‘”. Both of the raps were off-the-cuff vocals, and they make the song. “Too Much Blood” succeeds because it has a great bass line, and because it’s funny. The video, with a campy, scared Jagger running away from chainsaw-wielding Keith and Woody, is even more amusing (in an admittedly dark way).

In a way, it’s easy to see why many fans dismissed Undercover. The middle of the album is a three song sequence that starts with the awful “Feel On Baby”, continues to the dance/rap hybrid of “Too Much Blood”, and culminates in the funk of “Pretty Beat Up”. If the Black and Blue album is what funky dance music sounded like in 1976, then “Pretty Beat Up” is what it sounded like in 1983. It’s a junk lyric, but it’s got a solid groove and a good sax solo from David Sanborn. Still, it’s the third song in a row that can’t really be classified as rock and roll or blues, so it’s the Stones playing outside of their strengths. “Pretty Beat Up” is good. It’s closer in spirit to Tattoo You‘s “Black Limousine” than Black and Blue‘s “Hot Stuff”, which makes it one of the band’s better excursions into funk.

The fans who stuck with the album through these three songs were paid off with “Too Tough”, “All The Way Down”, and “It Must Be Hell”. Jagger plays the strutting macho man of “Too Tough”, a riposte to an aggressive, possibly psychotic, woman who tried (and failed) to put the singer under her thumb. It’s the flip to “She Was Hot” with Jagger boasting of his victory over his female adversary. It’s a thoroughly convincing rocker, with Charlie once again on target and Ron Wood tearing into a quasi-heavy metal guitar solo.

Even better is “All The Way Down”, a sleazy rocker about a youthful affair. Jagger has commented that the song was based on an old relationship and the opening lyric, “I was 21, naïve/Not cynical, I tried to please” would seem to indicate that the girl in question may be Marianne Faithfull who, in 1983 when Undercover was released, was deep in the throes of drug addiction. “Still I play the fool and strut,” Jagger sings in a proto-rap style before shouting “Still you’re a slut!” It’s a harsh, angry song but there’s an undercurrent of lost affection in the bridge as Jagger croons “She’s there when I close my eyes” and also a real sense of lost time, innocence, and youth. “Still the years rush on by/Birthdays, kids, and suicides…Was every minute just a waste? Was every hour a foolish chase?” With Keith and Woody lending strong support, the chorus line of “She went all the way/All the way down” can serve as the obvious sexual reference it is but, assuming the song is about Faithfull, also a judgement about her life, now that the beautiful songbird of Swingin’ London had become a croaking, haggard junkie (she has, fortunately, cleaned up her act).

“It Must Be Hell” ends the album as it began, with another foray into politics. In this case, Jagger compares his life in the West with the one lived by those on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Lyrically, it’s a little sloppy. Jagger has admitted that the words weren’t as clear as he would have liked, especially in the first two verses. The closing summation makes his point, though, that as troubled as the West may have been, things were far worse under Communist rule:

Keep in a straight line, stay in tune

No need to worry, only fools

End up in prison or conscience cells

Or in asylums they help to build

We’re free to worship, free to speak

We’re free to kill, it’s guaranteed

We’ve got our problems, that’s for sure

Clean up the backyard, don’t lock the door

Musically, “It Must Be Hell” draws on a more unlikely source: the Stones themselves. The main guitar riff is a slightly altered variation of the chorus riff on Exile on Main Street‘s “Soul Survivor”. (Hey, it’s a great riff…Slash ripped it off for Michael Jackson’s “Black or White”, too.) At just over five minutes, “It Must Be Hell” overstays its welcome a little, but it’s a fine, propulsive rocker with scorched earth guitar work from Ron Wood.

Undercover was an experiment, an attempt to sound very contemporary. It was the last time the Stones would be this daring on an album. Experiments would be few over the rest of their career, which is unfortunate. Soon after this album the band would settle into workmanlike songwriting and playing that provided lots of good material, almost none of which were as memorable as their best music. In 1983 the Stones were fracturing. Keith and Mick were at each other’s throats, which is clearly evident in the lyrics on Undercover. It’s an album where the songs are steeped in violent metaphors and allusions. Even sex, Jagger’s leitmotif, has become violent. Nearly every song carries this theme: “Pretty Beat Up”, “Tie You Up”, “Too Tough”, “It Must Be Hell”, and that doesn’t even include the themes as shown in songs with more innocent titles: revolution, recrimination, bitterness, anger. What you’ve got with Undercover is an album where the band was working as a unit, but where the two songwriters and leaders were filled with passion. The anger would be even more pronounced later, but by then the unity was gone. By the time the unity returned, the passion was lost to an uneasy détente. That makes Undercover the last album made by the Rolling Stones as a vibrant, intense rock group. From here on they would be a working band, driven by habit, finance, and professionalism. Undercover has its flaws, but is a largely underrated album in the Stones discography. It’s the last album where the Stones sound like they were really trying, and that has to count for something.

Grade: B