Trying to track down the Big Bang of any type of music is a fool’s game. Every genre has multiple antecedents. This is particularly true of rock music, which has many rivers feeding into its ocean. Several years ago, a new genre was coined: “Americana.” Truth is, there was absolutely nothing new in this genre. It goes back to Sun Studios and the initial blending of country music and rhythm and blues. Elvis Presley singing “Blue Moon of Kentucky” is as Americana as it gets. It was dubbed rock and roll.

Over the ensuing years, other threads were added to the tapestry. The Byrds brought folk music into the mix, and it was dubbed “folk rock.” They also incorporated country music into their repertoire. In 1967 Bob Dylan traded in his wild mercury sound for sparse instrumentation and acoustic music with John Wesley Harding. He was followed in 1968 by his old backing group The Band and their Music From Big Pink, an album of almost incalculable influence. The Beau Brummels, famed for their British Invasion-style hits “Just A Little” and “Laugh, Laugh” made a hard turn left with their country- and folk-inspired Bradley’s Barn LP. And it was called roots music.

The biggest musical shock of 1968 was likely the Byrds and their terrific album Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Here was an album that was made by a well-established rock group, but the sound was stone-cold country music. Although the Byrds had always dabbled in country, Sweetheart was a complete stylistic change. This was due to the influence of a country singer who loved rock and roll, Gram Parsons.

Parsons had been kicking around for a few years and had released an album with the International Submarine Band (so many bonus points for naming themselves after a Little Rascals joke). He befriended the Byrds’ Chris Hillman and was brought into that group. Such was his presence that even the founder of the band, Roger McGuinn, bought fully into the country sound.

It is here, from his time in the Submarine Band through his short stint with the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers to his time as Keith Richards’s drug buddy and through his all-too-brief solo career, that David N. Meyer’s 2007 biography Twenty Thousand Roads: The Ballad of Gram Parsons and His Cosmic American Music stands as a definitive work.

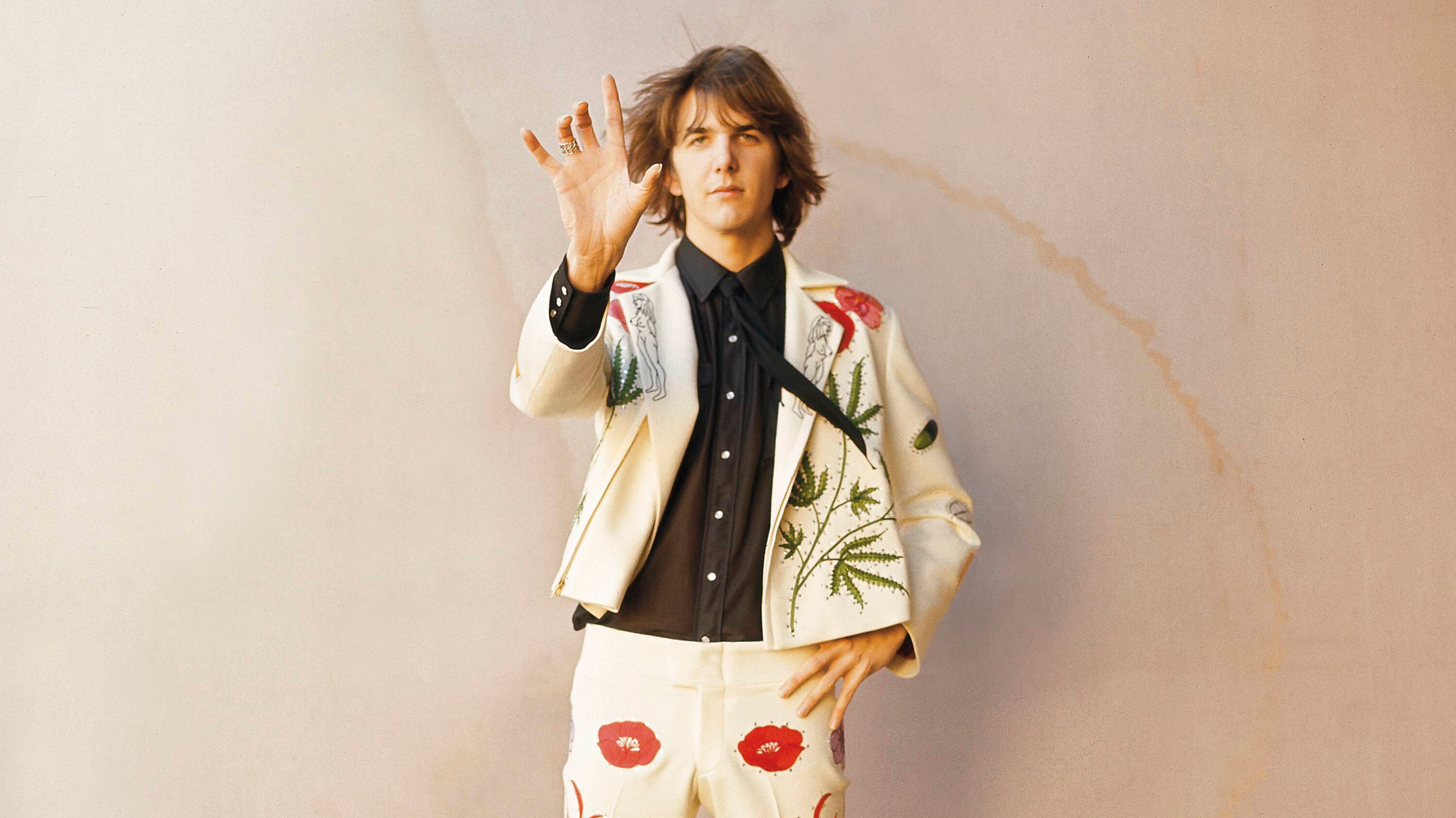

Meyer’s greatest achievement is his incisive exploration of Parsons’ musical legacy. He dissects what Parsons called “Cosmic American Music,” a blending of country, rock, soul, and folk with precise attention to detail. He frames the style as a radical synthesis of country’s emotional authenticity, rock’s rebellious energy, and soul’s spiritual depth. The book meticulously traces Parsons’ evolution from the International Submarine Band’s tentative experiments to Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which Meyer argues was a cultural pivot point for country-rock. His analysis of Parsons’ tenure with the Flying Burrito Brothers, particularly albums like 1969’s The Gilded Palace of Sin, highlights their blend of Nudie-suited theatricality and raw vulnerability. Meyer’s close readings of songs like “Hickory Wind” and “Sin City” reveal their lyrical and sonic complexity, positioning them as archetypes of Americana’s introspective ethos. His discussion of Parsons’ collaboration with his protégé Emmylou Harris on 1973’s GP and 1974’s posthumous Grievous Angel is especially good, portraying the duets as high art. Meyer convincingly argues that Parsons’ influence—evident in the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street, Wilco’s experimentalism, and the alt-country movement—stems from his ability to transcend genre. This was a man who felt comfortable adding distortion to pedal steel (an unforgivable sin in country music at the time) and who did a fine rendition of “Cry One More Time” by Boston’s answer to the Rolling Stones, the J. Geils Band. With the Burrito Brothers he was also the first to record and release “Wild Horses,” predating the Stones’ classic recording on Sticky Fingers by a year.

The biography’s portrayal of Parsons’ life is equally rigorous. It’s clear that Meyer is a fan, but he’s able to look at the singer objectively. Parsons’s youth is portrayed as something out of a William Faulkner novel, born and raised fabulously wealthy in a highly dysfunctional family torn and frayed by alcoholism and tragedy. This context informs Parsons’ paradoxical character: a charismatic innovator whose idealism and prodigious talent was undercut by self-destructive tendencies. Meyer’s research—drawing on interviews with obscure associates and bandmates—illuminates Parsons’ relationships, notably his influence on Keith Richards and his creative partnership with Chris Hillman. The book avoids hagiography, candidly addressing Parsons’ heroin addiction, erratic behavior, and professional unreliability, which Meyer frames as both a personal failing and a byproduct of the 1960s counterculture’s excesses. This approach yields a complex portrait of the artist as a young man: Parsons as a catalyst for musical change, yet someone whose potential was curtailed by his inability to harness his own genius. Meyer’s vivid prose captures the era’s cultural ferment—Los Angeles’ Laurel Canyon scene, country music’s resistance to rock, and the transatlantic exchange with the Rolling Stones—making the biography a valuable cultural history as well as a personal one.

It must be said that the book gets off to a rough start. A reader would be forgiven for abandoning the story fairly deep into it. Approximately 30% of the book, almost the entire first third, is a forensic detailing of Parson’s family history going back to his grandparents. Page after page is filled with the minutiae of their business dealings, their successes, their failures, their trouble with alcohol, distant relatives, childhood friends. The subject of the book is barely a character and deep into the book there’s still plenty of discussion about his eighth-grade band and his high school years. This excruciating level of detail proves that Meyer did his research, interviewing virtually everybody whose life intersected with Parsons, but a good editor could have told him to summarize it all in one chapter. It’s an interesting detail that the Parsons family at one point owned a full third of the orange and citrus business in Florida, but you don’t have to read about every business dealing on the way to their fortune. The writing here is self-indulgent and unnecessary.

Once the reader gets past this, the story takes off, culminating in a motel room in Joshua Tree National Park. The story of Gram Parsons’ death from an overdose of morphine and tequila is tragic; the immediate aftermath is a sick farce. Meyer does not romanticize this story, as many have in the past. It is not the ultimate farewell to a shining star as Parsons’ road manager Phil Kaufman tries desperately to portray it. Kaufman’s theft of Parsons’ body, and the gasoline-fueled cremation of his naked, recently autopsied corpse in Joshua Tree is now the stuff of gruesome legend. It matters not that Parsons and Kaufman had pledged to do this in case one of them died. It was a reckless, drug-fueled promise that should have been broken, and Parsons should have been buried with dignity.

Twenty Thousand Roads is a much-needed biography of a figure that, as much as any single person, can rightfully be called the father of Americana. He was building on influences from Buck Owens to the Rolling Stones, but the sound coalesced on his wonderful solo albums and his work with the Flying Burrito Brothers. One listen to the heartbreak of “$1000 Wedding” or “Love Hurts” and the spinning road tale of “Return of the Grievous Angel” and you can hear the entire history of country music as well as the key to the future of the genre. Gram Parsons was the real deal, the performer that the Eagles desperately wanted to be, though they could not hope to measure up. You can hear Parsons’ influence through the subsequent years. It’s in the cow punk of Jason and the Scorchers, the Southern Gothic sound of early R.E.M., the alt-country stylings of Lone Justice, the Long Ryders, Uncle Tupelo, the Jayhawks, and so many more. None of those bands were labeled as Americana because the term didn’t exist until marketing departments became desperate to hang a label on the sound, but they all tie back to Parsons. Much of the modern sound of country (I’m talking real country, not that godawful “sittin’ in my pickup with my dog, drinking a beer, wearing my blue jeans and Stetson, looking to raise trouble” bro-country) owes allegiance to a singer who was scorned by Nashville for decades until the music scene caught up to him. He was, in the prescient song by fellow Burrito Brother and future Eagle Bernie Leadon, “God’s own singer.”

A simple drum beat opens the festivities here, accompanied by various grunts from the singer who’s warming up in the wings, before the incredibly loud, magisterial organ comes in. Spooky Tooth has arrived and, with them, the beginnings of the Progressive Rock movement that would flower in the following years.

A simple drum beat opens the festivities here, accompanied by various grunts from the singer who’s warming up in the wings, before the incredibly loud, magisterial organ comes in. Spooky Tooth has arrived and, with them, the beginnings of the Progressive Rock movement that would flower in the following years.