It’s almost impossible to believe, yet it remains true: You can compile a multi-disc Greatest Hits of the Beatles without including a single song from any of their albums. Such is the case with Past Masters, the collected singles, EPs, B-sides, and random tracks that never made it onto the band’s proper LPs. Most of the songs included did appear on the American versions of their albums, which cannibalized their singles to appear as hooks for the record buyer, but those LPs were creations of Capitol Records, not the band. The Beatles, and they were not the only act to have this opinion, believed that if you included singles on LPs you were ripping off the fans by getting them to buy the same music twice. It was really quite common in the mid-Sixties for an English band’s albums to be remarkably different than their American releases.

It’s almost impossible to believe, yet it remains true: You can compile a multi-disc Greatest Hits of the Beatles without including a single song from any of their albums. Such is the case with Past Masters, the collected singles, EPs, B-sides, and random tracks that never made it onto the band’s proper LPs. Most of the songs included did appear on the American versions of their albums, which cannibalized their singles to appear as hooks for the record buyer, but those LPs were creations of Capitol Records, not the band. The Beatles, and they were not the only act to have this opinion, believed that if you included singles on LPs you were ripping off the fans by getting them to buy the same music twice. It was really quite common in the mid-Sixties for an English band’s albums to be remarkably different than their American releases.

The Beatles, however, were a cut above. They were so prolific that they were churning out singles and EPs every couple of months, with a yearly (or sometimes twice yearly) LP release. Their musical output, driven by an insatiable demand, dwarfed the rest of the music scene by a large margin. Not only were they putting out a seemingly endless stream of new music, they were doing so at an astonishingly high level of quality. It was truly as if they didn’t want to be associated with anything mediocre or worse.

The singles, and the Past Masters collection, begins with “Love Me Do,” their moderately successful first single from 1962. Unbeknownst to most fans at the time, and even today, the single was a different version than the album track. The “Love Me Do” that appears on the Please Please Me album doesn’t feature Ringo Starr on drums. After the Pete Best debacle, George Martin brought in a professional studio drummer named Andy White to play instead of the unproven Ringo, who was relegated to tambourine. The version on Past Masters is the single version of the song, with Ringo on drums. It is, of course, a charming pop song circa the early Sixties (ironically, the pre-Beatles Sixties). There’s nothing much to the song except some nice harmonica and a good vocal hook. The lyrics are pretty bad, the instrumentation simple. There was no hint of what was to come.

From there Past Masters explodes with a dazzling string of singles from the effervescent “From Me to You” and “Thank You Girl” to the majestic “She Loves You” and “I Want To Hold Your Hand.” These last two songs, and their B-sides, “I’ll Get You” and the extraordinary harmonies of “This Boy,” are where the Beatle legend, and true Beatlemania, begins. “She Loves You” is the first Beatles track to use the trick of starting the song with the chorus, an instant ear worm that grabs the listener from the first seconds and demands full attention be paid. “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” co-written by Lennon and McCartney in the basement of Paul’s girlfriend’s (Jane Asher) house was the shot heard around the world, especially in America where it soared to the top of the charts and took up residence there until it was replaced by an American reissue of “She Loves You.” Released in America just before the assassination of John F. Kennedy, “I Want to Hold Your Hand” caught fire in the weeks following that national tragedy. The timing couldn’t have been better. When America was reeling and mourning, a propulsive song filled with the joy and wonder of new romance exploded onto the airwaves. Thousands of people lined up at the newly rechristened John F. Kennedy Airport in New York to welcome the long-haired lads from Liverpool. America was the last great step for the Beatles to assume musical world dominance.

Those two singles are followed on Past Masters by “Komm Gibb Mir Deine Hand” and “Sie Liebt Dich,” which featured the band singing “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “She Loves You” in German, done to recognize their fans in Germany, the first country where the Beatles began to really make a name for themselves. It was released as a single in Germany.

In England, the band released an EP called Long Tall Sally. Since there was no market for EPs in America, these songs were processed as album tracks on a “new” unauthorized American-only album. Paul McCartney’s frenetic take on Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally,” plus covers of “Slow Down” and “Matchbox” and the sole Lennon-McCartney track, the excellent “I Call Your Name” comprised the EP.

The band closed out 1964 with one of their best early singles, “I Feel Fine” backed with “She’s A Woman.” Both songs are fine rockers, the former one of the first (if not the first) songs to feature guitar feedback on record. Before Jeff Beck’s “Shapes of Things,” before Pete Townshend’s “My Generation,” and long before Jimi Hendrix turned feedback into art, John Lennon’s song starts with a single guitar note followed by a blast of feedback. The song ends with dogs barking very faintly in the fade-out. “She’s A Woman” is Paul’s contribution, featuring one of his best early vocals.

“Bad Boy,” a racing cover of a Larry Williams song, was included on the American-only Beatles VI in early 1965. That’s correct. In the span of 1964 Capitol Records had milked the Beatles three official albums (With the Beatles, A Hard Day’s Night, and Beatles for Sale), combined with the Long Tall Sally EP and the singles to release five albums in America. “Bad Boy” was really sort of the exception. It was released only in America until it turned up on a British greatest hits album (A Collection of Oldies But Goldies).

The first disc of Past Masters closes with two B-sides, the soaring “Yes It Is” which was the flip side of “Ticket To Ride” and the breakneck “plastic soul” of “I’m Down,” the flip of “Help!” “I’m Down” was never released on an album, even in England, and remained a lost track until it resurfaced in the 1970s on the Rock and Roll Music compilation. It remains a criminally unknown song, featuring one of Paul’s best vocals ever, wherein he beats his idol Little Richard at his own game.

The second disc of Past Masters also aligns neatly with the sudden maturity exhibited by the band. The early Beatles are now done and locked in the history books. Disc two begins with 1966’s “Day Tripper”/”We Can Work It Out” followed by one of the greatest singles of all time, “Paperback Writer”/”Rain”. While “We Can Work It Out” contained much of McCartney’s trademark sunny optimism, it’s tempered by Lennon’s bridge, which reminds the listener that “life is very short and there’s no time for fussing and fighting”. But it’s “Day Tripper” that ushers in a newer, heavier sound. Featuring a riff that Jimi Hendrix loved, and a lyric that’s simultaneously about drugs (in this case, LSD) and a very, um, frustrating woman (“she’s a big teaser/she took me half the way there” isn’t particularly subtle innuendo). “Paperback Writer” and “Rain” upped the ante, with both sides of the single being blasts of loud guitars and even louder bass from McCartney, heavily influenced by Motown savant Funk Brother James Jamerson. The production on these two songs is absolutely pristine. Despite the wall-of-sound nature of the songs, every instrument can be heard as clearly as if the band was standing in the room with you. Paul’s bass on “Rain” is particularly prominent and particularly good. It’s one of the great bass guitar recordings in rock and likely the first where that rhythm instrument is so loud in the mix, almost assuming lead duties. “Rain” also gets the nod for having the first backwards vocals on a pop or rock record.

In 1967 the Beatles singles were added to the English Magical Mystery Tour EP to create the album of the same name. This was the last time Capitol Records would rearrange the band’s output to make a few extra bucks. Since then, the American album Magical Mystery Tour has become so loved it was made canon in 1987 with the arrival of the Beatles on CD. As a result of that move, Past Masters does not include what were originally released as singles only: “Strawberry Fields Forever”/”Penny Lane”, “All You Need Is Love”/”Baby You’re A Rich Man” and “Hello, Goodbye” the A-side of “I Am the Walrus.”

The collection picks up again in 1968 with “Lady Madonna”/”The Inner Light”. The A-side is a rollicking, piano-pounding, Fats Domino-inspired number. The latter is one of George’s India-influenced sitar songs. “The Inner Light” has never been released on a Beatles album with the exception of Rarities in 1980. It’s a (mercifully) brief song that at least includes a backing vocal from John and Paul, a rarity on George’s India songs.

As good as “Lady Madonna” was, it held no comparison to the genius run of singles the Beatles had released since “Day Tripper” that included “Strawberry Fields,” “Penny Lane” and “I Am the Walrus” among others. The band had an ace up their sleeve with the next single, a song written by Paul as consolation for John’s son, Julian, as his parents were getting divorced. “Hey Jude” ended up being the most successful single the Beatles ever released, but in some ways that’s surprising. At the time it was the longest song ever released as a single, beating Dylan’s trailblazing “Like A Rolling Stone” by a full minute. The Beatles felt confident releasing such a long song (over seven minutes) because they knew there was no way the radio wouldn’t play it. Another reason its hit status was surprising is that the last four minutes of the song are given over to a mostly wordless chorus comprised of the band singing “Na na na na na na na hey Jude” over and over again. Not exactly hit material, that. What saves the fadeout from being boring is McCartney’s howling vocal interjections done in his best Little Richard voice while the music, complete with a 36-piece orchestra, builds inexorably around him. That’s hit material.

In the late summer of 1968 “Hey Jude” was pouring out of radio stations and jukeboxes everywhere, slamming into the number one slot and staying there for several weeks. Equally outstanding was the B-side, “Revolution.” This was the first time the Beatles were explicitly political in a song at a time when the New Left was rising in both America and Britain, and calls for revolution were dominating in political songs. Of course, the Beatles did it differently by making “Revolution” a song that was directly opposed to the rhetoric coming out of organizations like the Black Panthers and bands like Jefferson Airplane. “But when you talk about destruction/Don’t you know that you can count me out,” John sings over a wall of heavy, distorted guitars. Lennon did want it both ways, however. In both the video for the song and the slower, more acoustic version recorded for the White Album, he changes the lyric to “count me out…in.”

The band was fraying around the edges at this point in their career. In January of 1969, less than two months after the release of their 30-song self-titled opus, the band was back in the studio. Under enormous pressure to write and record a new album and then do a single live show, the fraying got worse. George Harrison even quit at one point (memorializing the moment in his diary by writing “left the Beatles.”) George was back a few days later, and the band continued. There were some great ideas for songs floating around, but they simply couldn’t seem to get it together to bring the ideas to their full potential. The exception was their next single, “Get Back”/”Don’t Let Me Down.” The latter song was brought to the sessions by John, a heart-rending plea from a very insecure man to his new lover. The A-side of the single was created completely in the studio. There is a part in Peter Jackson’s extraordinary documentary look at these session, Get Back, where McCartney is heard playing around on guitar. The chords he’s riffing on have no words attached and are sort of formless, but gradually they begin to take shape and McCartney begins extemporizing mostly nonsense lyrics. It’s a fascinating process watching the song “Get Back” being written right before your eyes. The single was released in April of 1969, after the Beatles had given up recording the album they’d started in January. The version of “Get Back” that appears on Past Masters is a completely different mix than the version that would eventually appear on the album Let It Be.

The next single reflected where the Beatles were at that moment. Released only one month after “Get Back”, “The Ballad of John and Yoko”/”Old Brown Shoe” features a Ringo-less band. Since Ringo was taking some time away to work on the Peter Sellers film “The Magic Christian,” George Harrison’s “Old Brown Shoe” was recorded with McCartney on drums. The real question is, “Who plays bass?” The song features a very McCartney-esque bass line but George always maintained that it was he who played the bass. My money’s on McCartney. The galloping bass line is too loud, too busy without being overwhelming. Harrison was a fine guitarist, but there’s nothing in his entire recorded output that suggests he could play the bass in a fashion even approximating his Beatle bandmate, one of the best bass players in the rock era. George sings and plays guitar and organ on the track, with John on piano.

Similarly, “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” was completed without the missing Ringo but also without George. Written and recorded in one day, this was the last Beatles song to be done exclusively for a single and features John on vocals and guitar and Paul on bass, drums, and vocals. The song is far from being a ballad. It’s a brisk rocker that tells the story of John and Yoko’s wedding and subsequent honeymoon with all of Lennon’s trademark wit and humor. Paul’s drumming is particularly good. As Beatle singles go, “The Ballad of John and Yoko”/”Old Brown Shoe” is one of their lesser efforts as enjoyable as it might be. It simply doesn’t stand up against any of the singles they’d released since “She Loves You” started their run of genius work. Still, it’s a fun couple of songs.

The next Beatles single was not actually released by the band. “Across the Universe” was a song John had given to the World Wildlife Fund for a charity album called No One’s Gonna Change My World. It’s largely a throwaway collection of songs featuring The Beatles, the Hollies, and assorted C-list and D-list acts, which makes “Across the Universe” shine even brighter. Marrying one of Lennon’s best ever lyrics to a gorgeous melody, and overdubbed with the sound of a flock of birds, this is a remarkably different, and better, song than the one that appears on the album Let It Be. The song was recorded in early 1968 and was originally considered to be the B-side to “Lady Madonna” but was shelved until Lennon gave it away.

The Beatles broke up in April of 1970, when a staggeringly passive-aggressive McCartney released a phony interview where he told the world that he didn’t see working with John ever again. One month prior, the Beatles sent their parting shot to the music world with the release of the single “Let It Be”/”You Know My Name (Look Up the Number).” The A-side really requires no explanation. It’s a very different mix than the one that would show up two months later on the album of the same name. The overdubs are largely absent and the guitar solo is wildly different. The B-side, however, was…something else entirely. The basic track was originally recorded in 1967, and included The Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones playing a saxophone. Vocals were added in April of 1969. The entire song is an extended joke, with John and Paul using funny voices mostly repeating the titular phrase over disjointed music. It’s not something most Beatle fans listen to on repeat. It’s not even something that most Beatle fans have even heard. It is, however, a wonderfully idiosyncratic, humorous goof that reminds the listeners that the Beatles were, above all, fun.

From October 1962 to March 1970, just seven and a half years, the Beatles released a mind-blowing 33 songs that did not appear anywhere on their officially released albums. Compiled here on Past Masters they are an easy-to-follow roadmap for the astounding leaps in maturity, creativity, and musical genius the band displayed. It’s almost impossible to believe that the band that released “Love Me Do” was the same band that released “Strawberry Fields” just four and a half years later, and then “Hey Jude” just a year and a half after that. The musical growth of the Beatles was off-the-charts, and unmatched by any band before or since. The best example of this growth is heard here, in the singles collected on Past Masters.

Grade: A+

As the Rolling Stones got older, long past the retirement age of mere mortals, and as Jagger’s salacious sex addict lyrics sounded sillier and sillier coming out of his wrinkled puss, fans such as myself began wishing that the Stones would show a little dignity in their old age and go back to their first love: blues. A solid blues album, maybe with a few acoustic blues numbers and a Chuck Berry cover or two, would be a great way for the band to come to the end of the line. Full circle, and all that cal. In 2016, the band delivered, though not quite in the hoped-for way. Rather than a bunch of Jagger/Richards originals, the blues album they delivered was all cover songs, mostly more obscure numbers. There would be no clichéd versions of “Got My Mojo Working” or “Smokestack Lightning” here. The Stones, befitting the blues aficionados they are, dug a little deeper. The only well-known song on here to the average rock music fan is “I Can’t Quit You Baby,” once covered by Led Zeppelin.

As the Rolling Stones got older, long past the retirement age of mere mortals, and as Jagger’s salacious sex addict lyrics sounded sillier and sillier coming out of his wrinkled puss, fans such as myself began wishing that the Stones would show a little dignity in their old age and go back to their first love: blues. A solid blues album, maybe with a few acoustic blues numbers and a Chuck Berry cover or two, would be a great way for the band to come to the end of the line. Full circle, and all that cal. In 2016, the band delivered, though not quite in the hoped-for way. Rather than a bunch of Jagger/Richards originals, the blues album they delivered was all cover songs, mostly more obscure numbers. There would be no clichéd versions of “Got My Mojo Working” or “Smokestack Lightning” here. The Stones, befitting the blues aficionados they are, dug a little deeper. The only well-known song on here to the average rock music fan is “I Can’t Quit You Baby,” once covered by Led Zeppelin.

It’s almost impossible to believe, yet it remains true: You can compile a multi-disc Greatest Hits of the Beatles without including a single song from any of their albums. Such is the case with Past Masters, the collected singles, EPs, B-sides, and random tracks that never made it onto the band’s proper LPs. Most of the songs included did appear on the American versions of their albums, which cannibalized their singles to appear as hooks for the record buyer, but those LPs were creations of Capitol Records, not the band. The Beatles, and they were not the only act to have this opinion, believed that if you included singles on LPs you were ripping off the fans by getting them to buy the same music twice. It was really quite common in the mid-Sixties for an English band’s albums to be remarkably different than their American releases.

It’s almost impossible to believe, yet it remains true: You can compile a multi-disc Greatest Hits of the Beatles without including a single song from any of their albums. Such is the case with Past Masters, the collected singles, EPs, B-sides, and random tracks that never made it onto the band’s proper LPs. Most of the songs included did appear on the American versions of their albums, which cannibalized their singles to appear as hooks for the record buyer, but those LPs were creations of Capitol Records, not the band. The Beatles, and they were not the only act to have this opinion, believed that if you included singles on LPs you were ripping off the fans by getting them to buy the same music twice. It was really quite common in the mid-Sixties for an English band’s albums to be remarkably different than their American releases. A simple drum beat opens the festivities here, accompanied by various grunts from the singer who’s warming up in the wings, before the incredibly loud, magisterial organ comes in. Spooky Tooth has arrived and, with them, the beginnings of the Progressive Rock movement that would flower in the following years.

A simple drum beat opens the festivities here, accompanied by various grunts from the singer who’s warming up in the wings, before the incredibly loud, magisterial organ comes in. Spooky Tooth has arrived and, with them, the beginnings of the Progressive Rock movement that would flower in the following years.

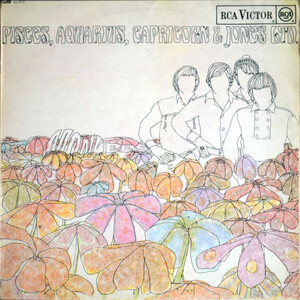

It’s an easy mistake to make, to judge The Monkees by their hit singles without ever diving any deeper. After all, it’s not like they were a real band driven to make artistic statements over the course of an LP. But easy or not, it’s a mistake. In fact, the Monkees albums are a virtual treasure trove of potential hits; with a band constructed to be a hit machine, virtually all of the songs that were given to them were viewed as potential singles, and the songs written by the band members were their attempts to break the stranglehold the producers held over their product.

It’s an easy mistake to make, to judge The Monkees by their hit singles without ever diving any deeper. After all, it’s not like they were a real band driven to make artistic statements over the course of an LP. But easy or not, it’s a mistake. In fact, the Monkees albums are a virtual treasure trove of potential hits; with a band constructed to be a hit machine, virtually all of the songs that were given to them were viewed as potential singles, and the songs written by the band members were their attempts to break the stranglehold the producers held over their product.