Garage rock came out of the 1960s, a form of raw, back-to-basics rock and roll. The gateway drug for garage rock is the legendary collection Nuggets, originally compiled by future Patti Smith guitarist Lenny Kaye and released in 1972 as a two-record compilation of great lost tracks from the sixties. It has since been expanded into no fewer than five four-disc box sets, focusing on America, international, modern, Los Angeles and San Francisco. They represent an alternative view of the history of rock and roll, one where the big bands of the era are only heard through their influence. And it’s possible to hear all those influences in the three minutes it takes to spin out one of these songs. Part of the fun of garage rock is how it teases the ear, reminding you of something else but remaining fresh.

Garage rock came out of the 1960s, a form of raw, back-to-basics rock and roll. The gateway drug for garage rock is the legendary collection Nuggets, originally compiled by future Patti Smith guitarist Lenny Kaye and released in 1972 as a two-record compilation of great lost tracks from the sixties. It has since been expanded into no fewer than five four-disc box sets, focusing on America, international, modern, Los Angeles and San Francisco. They represent an alternative view of the history of rock and roll, one where the big bands of the era are only heard through their influence. And it’s possible to hear all those influences in the three minutes it takes to spin out one of these songs. Part of the fun of garage rock is how it teases the ear, reminding you of something else but remaining fresh.

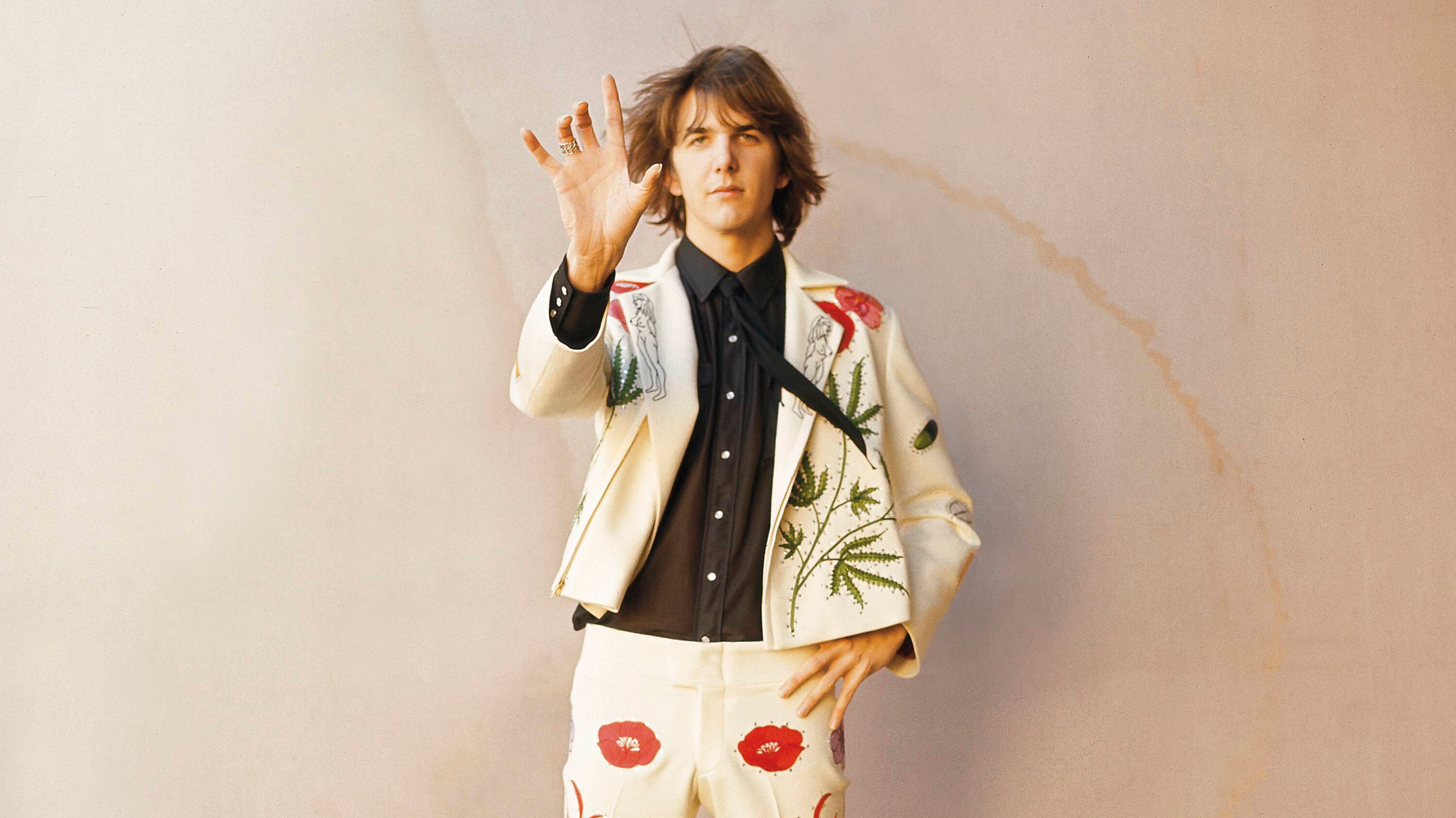

New Jersey’s Grip Weeds, named after John Lennon’s character in the movie How I Won The War, is a modern garage rock band that has just released their ninth album, Soul Bender. They are also in many ways the definitive band in this genre. The influences are there: the jangly guitars of The Byrds, the cascading drums of The Who, the harmonies of the Beatles, etc. But the beauty of the Grip Weeds is that they have assimilated their influences so well that they transcend them. On Nuggets it’s easy to say, “This band sounds like The Yardbirds” or “This could be a Kinks song.” The Grip Weeds sound like The Grip Weeds and simultaneously nobody else and everybody else. Many bands wear their influences on their sleeves. The Grip Weeds have them etched into their DNA.

Soul Bender captures the band at their best. It features the differing patterns of the 1960s in a distinctly modern weave. Released in June of this year on JEM Records and recorded at the band’s own House of Vibes studio, the album is a tour-de-force of melody, guitar crunch, a pounding rhythm section, and exquisite vocals. The result is reminiscent of a time long ago yet also timeless.

From the “Hard Day’s Night”-ish opening chord of the title track to the Odessey and Oracle feel of “Love Comes in Different Ways” the influences are there for trainspotters but make no mistake, this is an original band playing original music. Kurt Reil (vocals, drums), Rick Reil (guitar, keyboards, vocals), Kristin Pinell Reil (lead guitar, vocals), and Dave DeSantis (bass, vocals) have created a heady confection that is one of the best albums of the year (maybe the best).

The music on Soul Bender is varied without ever losing sight of the goal. From the loping duet between Kurt Reil and Kristin Pinell Reil on “Promise (Of The Real)” to the breathy psychedelia of “Column Of Air” to the Byrds-y “Gene Clark (Broken Wing)”, Soul Bender presents what is essentially a hidden greatest hits of a bygone era gussied up with a 21st century sheen and modern production values. The effect is never less than a joyful blast of what the radio should sound like today.

The secret weapon of the band is undoubtedly Kristen Reil. Aside from sterling harmonies and the occasional lead vocal (her voice on “If You Were Here” could have come straight out of Susanna Hoff’s mouth), she’s also an ace guitarist. Her lead guitar adds a level of excitement to the songs, particularly on “Conquer and Divide”, where she steps to the fore and plays two volcanic solos that lean heavy on the whammy bar. There’s a good reason Little Steven’s Underground Garage channel on Sirius named it the “Coolest Song of the Week.”

It’s heartening to hear new music like this. From their first album (House of Vibes) way back in 1994 the Grip Weeds have maintained an astonishing level of consistency in their work. Over nine studio albums (one of them, Strange Change Machine, a double CD set), plus a live album, a Christmas album (!), and a covers album (Dig) the band is still going strong, sounding as fresh now as they did when Nirvana and Pearl Jam were all over the radio. It’s no mean trick to sound so nostalgic and so new at the same time, but they pull it off with memorable tunes, great production, and incendiary playing. The Grip Weeds are the real deal.

Grade: A

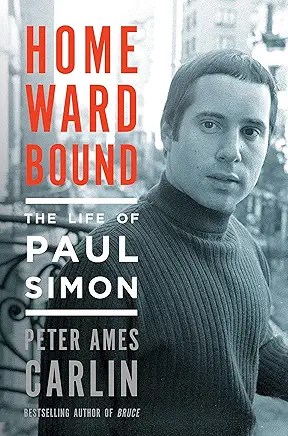

The poet half to Art Garfunkel’s one-man band has always been an interesting guy. Like Bob Dylan, he was a rock ‘n’ roll fan who went deep into the folk music scene only to reemerge with a sublime combination of the two genres. He achieved massive levels of fame and fortune, gathering critical hosannas the entire time, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice and now, in his 80s, is still releasing music. All of this, but Peter Ames Carlin’s 2016 biography was the first serious attempt at capturing this life on the page. The story covers Simon’s entire life from his days as a baseball fanatic kid growing up in Queens, New York through his years with Garfunkel and on through his solo career. Simon was not a particularly prolific artist, his solo albums being years apart, but the high quality of the work from “The Sound of Silence” to Graceland and beyond is unassailable.

The poet half to Art Garfunkel’s one-man band has always been an interesting guy. Like Bob Dylan, he was a rock ‘n’ roll fan who went deep into the folk music scene only to reemerge with a sublime combination of the two genres. He achieved massive levels of fame and fortune, gathering critical hosannas the entire time, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice and now, in his 80s, is still releasing music. All of this, but Peter Ames Carlin’s 2016 biography was the first serious attempt at capturing this life on the page. The story covers Simon’s entire life from his days as a baseball fanatic kid growing up in Queens, New York through his years with Garfunkel and on through his solo career. Simon was not a particularly prolific artist, his solo albums being years apart, but the high quality of the work from “The Sound of Silence” to Graceland and beyond is unassailable. A simple drum beat opens the festivities here, accompanied by various grunts from the singer who’s warming up in the wings, before the incredibly loud, magisterial organ comes in. Spooky Tooth has arrived and, with them, the beginnings of the Progressive Rock movement that would flower in the following years.

A simple drum beat opens the festivities here, accompanied by various grunts from the singer who’s warming up in the wings, before the incredibly loud, magisterial organ comes in. Spooky Tooth has arrived and, with them, the beginnings of the Progressive Rock movement that would flower in the following years.