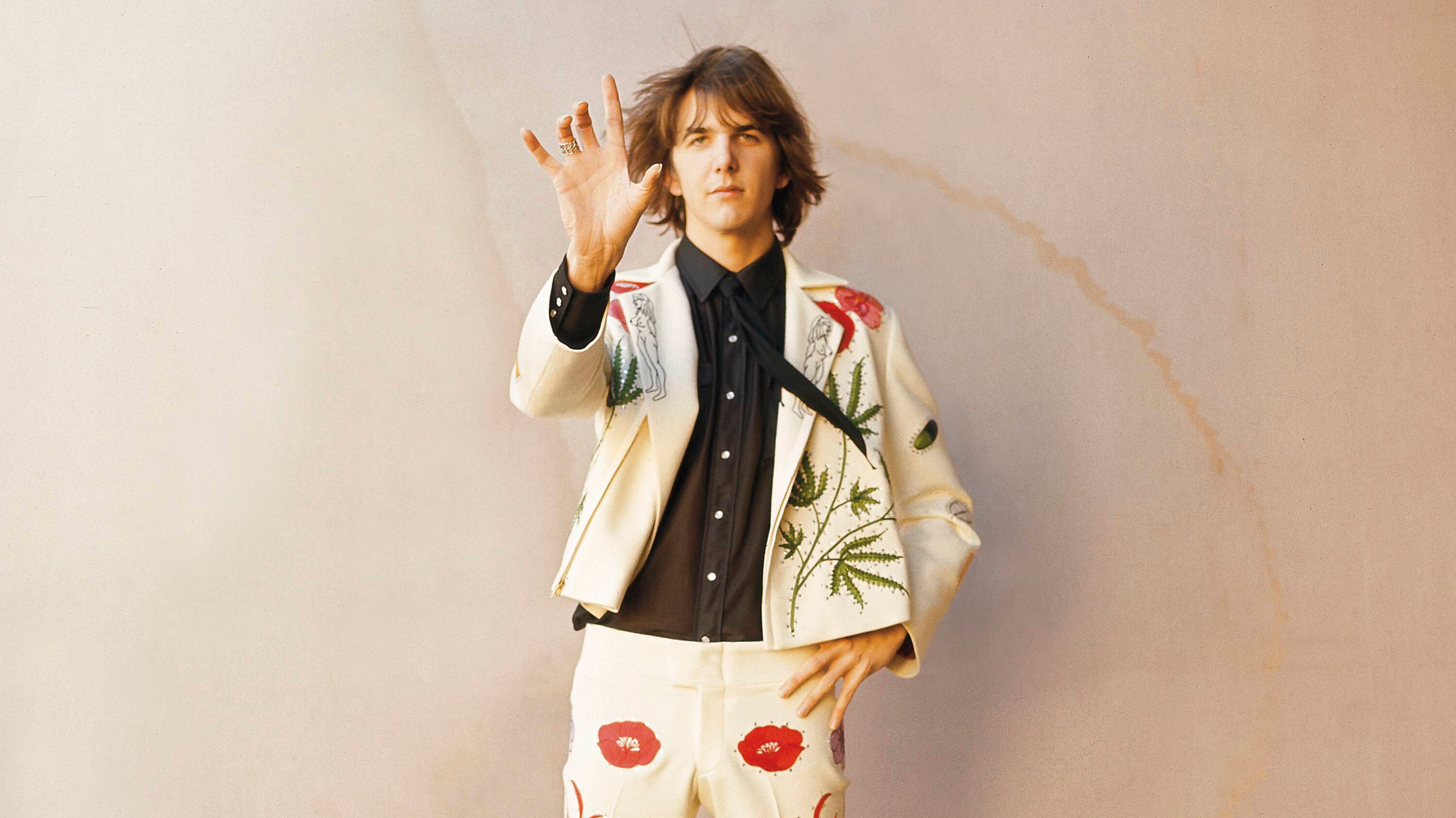

In 2008 a brash rocker came out of San Francisco with his first, self-titled, album. Ty Segall was a brief, noisy album of distinctly lo-fi rock. Under the murk and the distortion was a Nuggets-style garage rock album (at 23 minutes closer to an EP). Since then Segall has been releasing albums on his own and with various side projects at a pace that even Ryan Adams and Guided By Voices can’t hope to match. By my count, he’s put out 28 albums in the past 18 years. Of course, anyone who is that prolific is someone who by definition does not have an editor, and Segall has released some real junk over the course of his career. Some of his albums border on noise, and not a pleasant noise. But Segall is also capable of writing some incredible songs, and several of his albums are truly excellent. Such is the story of a restless, inventive musician who clearly burns with the desire to create. A new Ty Segall album is always worth checking out because you never know what to expect, and when he’s good he’s exceptional.

In 2008 a brash rocker came out of San Francisco with his first, self-titled, album. Ty Segall was a brief, noisy album of distinctly lo-fi rock. Under the murk and the distortion was a Nuggets-style garage rock album (at 23 minutes closer to an EP). Since then Segall has been releasing albums on his own and with various side projects at a pace that even Ryan Adams and Guided By Voices can’t hope to match. By my count, he’s put out 28 albums in the past 18 years. Of course, anyone who is that prolific is someone who by definition does not have an editor, and Segall has released some real junk over the course of his career. Some of his albums border on noise, and not a pleasant noise. But Segall is also capable of writing some incredible songs, and several of his albums are truly excellent. Such is the story of a restless, inventive musician who clearly burns with the desire to create. A new Ty Segall album is always worth checking out because you never know what to expect, and when he’s good he’s exceptional.

Segall is at his best when he leaves the lo-fi aesthetic behind and records conventional rock songs. This is when he combines the raw power of The Stooges, the Glam rock of T. Rex, and psychedelic influences of early Pink Floyd and Sixties garage rock and emerges with something that is distinctly his own. Possession is Segall at his best.

Released in May 2025, Segall circles back to the sweet spot he hit with 2014’s Manipulator, when he traded in lo-fi chaos for sharp production, tight songs, and a stunningly high level of pop craftsmanship. The rough edges were still there; Segall is, at the end of the day, a descendent of garage rock, but Manipulator was a huge step forward that proved he was capable of moving from the garage to the arena. At least to theaters. Though it was released eleven years later, Possession is the spiritual successor to that earlier album, taking Manipulator‘s advances and building on them. It is tighter, punchier, more focused, and packed to the rafters with smart pop sensibilities. Where the earlier album sprawled over 17 songs in nearly an hour of music, Possession has no excess baggage, clocking in at a concise 40 minutes over 10 songs.

Every song on the album is a gem, and reflects the variety found across Segall’s earlier albums while retaining a consistency of sound and approach that is occasionally lacking. The fact that this album comes on the heels of 2024’s Love Rudiments, a nearly unlistenable album of instrumental percussion tracks, makes it all the more remarkable. It’s as if Segall knew he was going off the deep end and made a decision to get back to basics: bright acoustic guitars, fuzzy electric guitars, smart lyrics, great melodies, and tight songs. This is the sound of a genuine artist who has assembled a lifetime of influences and brewed them into something entirely his own. Over a career this inability to repeat himself, while admirable, has led to a remarkable inconsistency.

Segall plays almost everything on the album including all guitars, bass, drums, and vocals and it’s an impressive feat because it never sounds like it isn’t a full band playing off each other. Most one-man shows have the sound of one ginormous ego trip, but Segall plays every instrument with equal facility and with sympathy for each. He is one of rock’s most tireless and inventive voices.

From the album’s opening, the 1970s-infused blast of sunshine “Shoplifter” segueing into the pop genius of the title track, Possession offers up one treasure after another. “Buildings” taps into Segall’s Glam influences, sounding like a mutant T. Rex outtake. “Shining” delivers a huge chorus and ferocious guitar work, while “Skirts of Heaven” slows things down while retaining the dirty sound of Segall’s guitar in a nice counterpoint to an excellent string and horn section. Perhaps best of all, maybe even the highlight of his career, is “Fantastic Tomb,” a story song that ties together the tale of a robbery gone wrong and Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado” over two distinct music motifs (and an absolutely ripping guitar solo near the end of the track).

The album ends as strongly as it begins. There truly isn’t a wasted note here. “Another California Song” ends the album on a funny note even as the lyrics tell the familiar tale of failed dreams so prevalent in Los Angeles. It provides a more than suitable closing to the album by taking all the elements of the preceding songs and blending them into a sweet confection undercut with bitter lyrics.

Possession stands at the top of Segall’s work, surpassing even the excellent Manipulator and 2018’s sprawling epic Freedom’s Goblin. It’s the most mature work he’s done to this date, in addition to being the catchiest and smartest collection of his songs. At a time when rock music is back on its heels, this album is an essential listen.

Grade: A+

Garage rock came out of the 1960s, a form of raw, back-to-basics rock and roll. The gateway drug for garage rock is the legendary collection Nuggets, originally compiled by future Patti Smith guitarist Lenny Kaye and released in 1972 as a two-record compilation of great lost tracks from the sixties. It has since been expanded into no fewer than five four-disc box sets, focusing on America, international, modern, Los Angeles and San Francisco. They represent an alternative view of the history of rock and roll, one where the big bands of the era are only heard through their influence. And it’s possible to hear all those influences in the three minutes it takes to spin out one of these songs. Part of the fun of garage rock is how it teases the ear, reminding you of something else but remaining fresh.

Garage rock came out of the 1960s, a form of raw, back-to-basics rock and roll. The gateway drug for garage rock is the legendary collection Nuggets, originally compiled by future Patti Smith guitarist Lenny Kaye and released in 1972 as a two-record compilation of great lost tracks from the sixties. It has since been expanded into no fewer than five four-disc box sets, focusing on America, international, modern, Los Angeles and San Francisco. They represent an alternative view of the history of rock and roll, one where the big bands of the era are only heard through their influence. And it’s possible to hear all those influences in the three minutes it takes to spin out one of these songs. Part of the fun of garage rock is how it teases the ear, reminding you of something else but remaining fresh.

In the world of streaming music it’s virtually impossible for a band to break through into the public consciousness. Artists nowadays hope that their songs will be licensed to a commercial, or a video game, or a movie. Satellite radio exists, of course, but with so many stations to choose from, bands easily get lost in the shuffle. Today, albums are no longer the coin of the realm. The single has returned. Albums are still being made but that almost seems like a tradition more than an expression of artistry. The sad truth is that unless you’re selling (and streaming) in Taylor Swift-like numbers, a band today can’t make much (if any) money based on record sales. Money must be earned on the road, playing large and small clubs and theaters to a hopefully packed house.

In the world of streaming music it’s virtually impossible for a band to break through into the public consciousness. Artists nowadays hope that their songs will be licensed to a commercial, or a video game, or a movie. Satellite radio exists, of course, but with so many stations to choose from, bands easily get lost in the shuffle. Today, albums are no longer the coin of the realm. The single has returned. Albums are still being made but that almost seems like a tradition more than an expression of artistry. The sad truth is that unless you’re selling (and streaming) in Taylor Swift-like numbers, a band today can’t make much (if any) money based on record sales. Money must be earned on the road, playing large and small clubs and theaters to a hopefully packed house. When X first came on the scene in 1980 they were hardscrabble punk poets who had the good fortune to be noticed by former Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek, who was always a sucker for a band that wore their Doors influences on their sleeve. Those first four X albums (Los Angeles, Wild Gift, Under The Big Black Sun, and More Fun in the New World), all produced by Manzarek, still stand at the top of the Los Angeles punk scene from the late 1970s and 1980s. They were less aggressive than Black Flag, more tuneful than the Circle Jerks, less obnoxious than Fear, and, unlike the Germs, had written actual songs with melodies and choruses. Their combination of poetic lyrics, a punk rock rhythm section, and a Chuck Berry-loving rockabilly guitar player were unlike anything else on the scene. Their vocal harmonies were borrowed from Jefferson Airplane, their lyrical content from Jim Morrison. Though they came from the hardcore punk rock underground, that had more to do with their location than their actual sound. They were punk in attitude, but a rock and roll band in practice.

When X first came on the scene in 1980 they were hardscrabble punk poets who had the good fortune to be noticed by former Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek, who was always a sucker for a band that wore their Doors influences on their sleeve. Those first four X albums (Los Angeles, Wild Gift, Under The Big Black Sun, and More Fun in the New World), all produced by Manzarek, still stand at the top of the Los Angeles punk scene from the late 1970s and 1980s. They were less aggressive than Black Flag, more tuneful than the Circle Jerks, less obnoxious than Fear, and, unlike the Germs, had written actual songs with melodies and choruses. Their combination of poetic lyrics, a punk rock rhythm section, and a Chuck Berry-loving rockabilly guitar player were unlike anything else on the scene. Their vocal harmonies were borrowed from Jefferson Airplane, their lyrical content from Jim Morrison. Though they came from the hardcore punk rock underground, that had more to do with their location than their actual sound. They were punk in attitude, but a rock and roll band in practice.